|

The Federal Reserve Board is publicly weighing whether or not to ask Congress to allow it to establish a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC), replacing paper dollars with government-issued electrons.

Given the growth of computing, a digital national currency may seem inevitable. But it would be a risky proposition from the standpoint of cybersecurity, national security, and unintended consequences for the economy. A CBDC would certainly pose a significant threat to Americans’ privacy. A factsheet on the Federal Reserve website says, “Any CBDC would need to strike an appropriate balance between safeguarding the privacy rights of consumers and affording the transparency necessary to deter criminal activity.” The Fed imagines that such a scheme would rely on privacy-sector intermediaries to create digital wallets and protect consumers’ privacy. Given the hunger that officialdom in Washington, D.C., has shown for pulling in all our financial information – including a serious proposal to record transactions from bank accounts, digital wallets, and apps – the Fed’s balancing of our privacy against surveillance of the currency is troubling. With digital money, government would have in its hands the ability to surveil all transactions, tracing every dollar from recipient to spender. Armed with such power, the government could debank any number of disfavored groups or individuals. If this sounds implausible, consider that debanking was exactly the strategy the Canadian government used against the trucker protestors two years ago. Enter H.R. 1122 – the CBDC Anti-Surveillance State Act – which sets down requirements for a digital currency. This bill would prohibit the Federal Reserve from using CBDC to implement monetary policy. It would require the Fed to report the results of a study or pilot program to Congress on a quarterly basis and consult with the brain trust of the Fed’s regional banks. Though this bill prevents the Fed from issuing CBDC accounts to individuals directly, there is a potential loophole in this bill – the Fed might still maintain CBDC accounts for corporations (the “intermediaries” the Fed refers to). The sponsors may want to close any loopholes there. That’s a quibble, however. This bill, sponsored by Rep. Tom Emmer (R-MO), Majority Whip of the House, with almost 80 co-sponsors, is a needed warning to the Fed and to surveillance hawks that a financial surveillance state is unacceptable. A letter of protest sent by the lawyers of Rabbi Levi Illulian in August alleged that city officials of Beverly Hills, California, had investigated their client’s home for hosting religious gatherings for his family, neighbors, and friends. Worse, the city used increasingly invasive means, including surveilling people visiting the rabbi’s home, and flying a surveillance drone over his property.

A “notice of violation” from the city specifically threatened Illulian with civil and criminal proceedings for “religious activity” at his home. The notice further prohibited all religious activity at Illulian’s home with non-residents. With support from First Liberty Institute, the rabbi’s lawyers sent another letter detailing an egregious use of city resources to launch a “full-scale investigation against Rabbi Illulian” in which “city personnel engaged in multiple stakeouts of the home over many hours, effectively maintaining a governmental presence outside Rabbi Illulian’s home.” The rabbi’s Orthodox Jewish friends and family who visited his home had also received parking citations. The rabbi began to receive visits from the police for noise disturbances, such as on Halloween when other houses on the street were sources of noise as well. Police even threatened to charge Rabbi Illulian with a misdemeanor, confiscate his music equipment, and cite a visiting musician for violating the city’s noise ordinance, despite the obvious double-standard. First Liberty was active in publicizing the city’s actions. In the face of bad publicity about this aggressive enforcement, the city withdrew its violation notice late last year. That the city of Beverly Hills would blatantly monitor and harass a household over Shabbat prayers and religious holidays, particularly at a time of rising antisemitism, is made all the worse by sophisticated forms of surveillance aimed at the free exercise of religion. So city officials managed to abuse the Fourth Amendment to impinge on the First Amendment. This case is reminiscent of the surveillance of a church, Calvary Chapel San Jose, by Santa Clara, California, county officials, over its Covid-19 policies. Is there something about religious observances that attracts the ire of some local officials? Whatever their reasons, this story is the latest example of the need for local officials who are better acquainted with the Constitution. Agencies Must Release Policy Documents About Purchase of the Personal Data of 145 Members of Congress Late last week, Judge Rudolph Contreras ordered the NSA, the CIA, the FBI, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence to respond to a PPSA Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. The government now has two weeks to schedule the production of “policy documents” regarding the intelligence community’s acquisition and use of commercially available information regarding 145 current and former Members of Congress.

This is the second time Judge Contreras has had to tell federal agencies to respond to a FOIA request PPSA submitted. In late 2022, Judge Contreras rejected in part the FBI’s insistence that the Glomar doctrine allowed it to ignore FOIA’s requirement to search for responsive records. Despite that clear holding, the FBI – joined this time by several other agencies – again refused to search for records in response to PPSA’s FOIA request. And Judge Contreras had to remind the agencies again that FOIA’s search obligations cannot be ducked so easily. Instead, Judge Contreras found that PPSA “logically and plausibly” requested the policy documents about the acquisition of commercially available information. And Judge Contreras concluded that a blanket Glomar response, in which the government neither confirms nor denies the existence of the requested documents, is appropriate only when a Glomar response is justified for all categories of responsive records. The judge then described a hypothetical letter from a Member of Congress to the NSA that clarifies the distinction between operational and policy documents. He considered that such a letter might ask if the NSA “had purchased commercially available information on any of the listed Senators or Congresspeople” without revealing whether the NSA (or any other of the defendant agencies) “had a particular interest in surveilling the individual.” Judge Contreras decided that “it is difficult to see how a document such as this would reveal sensitive information about Defendants’ intelligence activities, sources, or methods.” It is on this reasoning that the judge ordered these agencies to produce these policies documents. We eagerly awaits the delivery of these documents in both cases. Stay tuned. PPSA today announced that it is asking the District Court for the District of Columbia to force the FBI to produce two records about communications between government agencies and Members of Congress concerning their possible “unmasking” in secretly intercepted foreign conversations under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA).

PPSA’s request to the court involves the practice of naming Americans – in this case, Members of the House and Senate – who are caught up in foreign surveillance summaries. In 2017, Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) said he had reason to believe his identify had been unmasked and that he had written to the FBI about it. Similar statements have been made by other Members of Congress of both parties. The matter seemed to have been settled in October 2022 when Judge Rudolph Contreras of the U.S. District Court of the District of Columbia declared that “communications between the FBI and Congress are a degree removed from FISA-derived documents and which discuss congressional unmasking as a matter of legislative interest, policy, or oversight … the FBI must conduct a search for any ‘policy documents’ in its possession.” The FBI had first refused to release these documents under a broad and untenable interpretation of the Glomar doctrine, under which the government asserts it can neither confirm nor deny the existence of such records for national security reasons. After Judge Contreras swept that excuse away, the FBI in October 2023 asserted that three FOIA exemptions allow it to withhold requested documents. The FBI has gone from obfuscation to outright defiance of the plain text of the law. It still claims that releasing correspondence with Congress would, somehow, endanger intelligence sources and methods. It is time for the court to step in and issue a legal order the FBI cannot openly defy. Thus PPSA’s cross motion for summary judgment knocks down the FBI’s rationale and asks Judge Contreras to order the FBI to produce all FBI records reflecting communications between the government and Members of Congress on their “unmasking.” Earlier, the FBI had searched under a court order to find two relevant policy documents. These unreleased records include a four-page email between FBI employees and an FBI Intelligence Program Policy Guide. Significant portions of both documents are being withheld by the FBI because, the Bureau now asserts, of the three exemptions. It claims the disclosure can be withheld because it could implicate sources and methods, the records were created for law enforcement purposes, and because of confidentiality. None of these excuses meet the laugh test for correspondence with Members of Congress. PPSA is optimistic the court will end the FBI’s two years of foot-dragging and order it to produce. Man proposes, God disposes, but Congress often just kicks the can down the road.

Throughout 2023, PPSA and our civil liberties allies made the case that Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act – enacted by Congress to give federal intelligence agencies the authority to surveil foreign threats abroad – has become a convenient excuse for warrantless domestic surveillance of millions of Americans in recent years. With Section 702 set to expire, the debate over reauthorizing this authority necessarily involves reforms and fixes to a law that functions in a radically different way than its Congressional authors imagined. In December, a strong bipartisan majority in the House Judiciary Committee passed a well-crafted bill to reauthorize FISA Section 702 – the Protect Liberty and End Warrantless Surveillance Act. This bill mandates a robust warrant requirement for U.S. person searches. It curtails the common government surveillance technique of “reverse targeting,” which uses Section 702 to work backwards to target Americans without a warrant. It also closes the loophole that allows government agencies to buy access to Americans’ most sensitive and personal information scraped from our apps and sold by data brokers. And the Protect Liberty Act requires the inclusion of lawyers with high-level clearances who are experts in civil liberties to ensure the secret FISA Court hears from them as well as from government attorneys. The FISA Reform and Reauthorization Act from the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence would not stop the widespread practice of backdoor searches of Americans’ information. And it does not address the outrageous practice of federal agencies buying up Americans’ most sensitive and private information from data brokers. In the crush of business, the deadline for reauthorizing Section 702 was delayed until early spring. Now the contest between the two approaches to Section 702 reauthorization begins in earnest. With a recent FreedomWorks/Demand Progress poll showing that 78 percent of Americans support strengthening privacy protections along the lines of those in the Protect Liberty Act, reformers go into the year with a strong tailwind. While we should never underestimate the guile of the intelligence community, reformers look to the debate ahead with hopefulness and eagerness to win this debate to protect the privacy of all Americans. In July, we wrote about revelations that the U.S. Department of Justice subpoenaed Google for the private data of House Intel staffers looking into the origins of the FBI’s Russiagate investigation. Then, in October, we wrote about a FOIA request from Empower Oversight seeking documents shedding light on the extent to which the executive branch is spying on Members of Congress. Now, following the launch of an official inquiry, Rep. Jim Jordan has issued a subpoena to Attorney General Merrick Garland for further information on the DOJ’s efforts to surveil Congress and congressional staff.

On Halloween, Jordan launched his inquiry into the DOJ’s apparent attempts to spy on Congress, sending letters to the CEOs of Alphabet, Apple, AT&T, T-Mobile, and Verizon requesting, for example, “[a]ll documents and communications between or among Apple employees and Justice Department employees referring or relating to subpoenas or requests issued by the Department of Justice to Apple for personal or official records or communications of Members of Congress or congressional staff….” Jordan also sent a letter to Garland, asserting that “[t]he Justice Department’s efforts to obtain the private communications of congressional staffers, including staffers conducting oversight of the Department, is wholly unacceptable and offends fundamental separation of powers principles as well as Congress’s constitutional authority to conduct oversight of the Justice Department.” Nearly two months later, according to Jordan, the DOJ’s response has been insufficient. In a letter to Garland dated December 19, 2023, Jordan says that the “Committee must resort to compulsory process” due to “the Department’s inadequate response to date.” That response, to be fair, did include a letter to Jordan dated December 4 conveying that the legal process used related to an investigation “into the unauthorized disclosure of classified information in a national media publication. Jordan, citing news reports, contends that the investigation actually “centered on FISA warrants obtained by the Justice Department on former Trump campaign associate Carter Page” (which the Justice Department Inspector General faulted for “significant inaccuracies and omissions”). Whatever the underlying motivation, Jordan is right to find DOJ’s explanation to date unsatisfying. Spying on Congress not only brings with it tremendous separation of powers concerns but raises a broader question about FISA and other processes that would reveal Americans’ personal information without sufficient predication. We need answers. Who authorized these DOJ subpoenas? And how can we make sure this kind of thing doesn’t happen again? PPSA looks forward to further developments in this story. Less consumer tracking leads to less fraud. That’s the key takeaway from a new study conducted by the National Bureau of Economic Research in its working paper, “Consumer Surveillance and Financial Fraud.”

Using data obtained from the Federal Trade Commission and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, as well as the geospatial data firm Safegraph, the authors looked at the correlation between Apple’s App Tracking Transparency framework and consumer fraud reports. Apple’s ATT policy requires user authorization before other apps can track and share customer data. In April 2021, Apple made this the default setting on all iPhones, ensuring that users would no longer be automatically tracked when they visit websites or use apps. This in turn dealt a hefty financial blow to companies like Snap, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, which collectively lost about $10 billion after implementation. The authors of the paper obtained fraud complaint figures from the FTC and the CFPB, then employed machine learning and targeted keyword searches to isolate complaints stemming from data privacy issues. They then cross-referenced those complaints with data acquired by Safegraph showing the number of iPhone users in a given ZIP code. According to the paper, a 10% increase in Apple users within a given ZIP code leads to a 3.21% reduction in financial fraud complaints. As the Electronic Frontier Foundation points out in a recent article about the study: “While the scope of the data is small, this is the first significant research we’ve seen that connects increased privacy with decreased fraud. This should matter to all of us. It reinforces that when companies take steps to protect our privacy, they also help protect us from financial fraud.” Obviously, more companies should follow Apple’s lead in implementing ATT-like policies. More than that, however, we need better and more robust laws on the books protecting consumer privacy. California has passed a number of related bills in recent years, most recently creating a one-stop opt-out mechanism for data collection. Colorado did the same. As other states and nations (and even CIA agents) wake up to the dangers of data tracking, this new study can serve as compelling, direct evidence showing why more restrictive settings – and consumer privacy – should always be the default. WSJ Graphical Roadmap: How Your Personal Information Migrates from App, to Broker, to the Government12/5/2023

A report in The Wall Street Journal does a masterful job of combining graphics and text to illustrate how technology embedded in our phones and computers to serve up ads also enables government surveillance of the American citizenry.

The WSJ has identified and mapped out a network of brokers and advertising exchanges whose data flows from apps to Defense Department, intelligence agencies, and the FBI. The WSJ has compiled this information into several illustrative animated graphs that bring the whole scheme to life. Here’s how it works: As soon as you open an ad-supported app on your phone, data from your device is recorded and transmitted to buyers. The moment before an app serves you an ad, all advertisers in the bidding process are given access to information about your device. The first information up for bids is your location, IP address, device, and browser type. Ad services also record information about your interests and develop intricate assumptions about you. Many data brokers regularly sell Americans’ information to the government, where it may be used for cybersecurity, counterterrorism, counterintelligence, and public safety – or whatever a federal agency deems as such. Polls show that Americans are increasingly concerned about their digital privacy but are also fatalistic and unaware about their privacy options as consumers. According to a recent poll by Pew published last month, 81 percent of U.S. adults are concerned about how companies use the data they collect. Seventy-one percent are concerned about how the government uses their data, up from 64 percent in 2019. There is also an increasing feeling of helplessness: 73 percent of adults say they have little to no control over what companies do with their data, while 79 percent feel the same towards the government. The number of concerned Americans rises to 89 percent when the issue of children’s online privacy is polled. Crucially, 72 percent of Americans believe there should be more regulation governing the use of digital data. Despite high levels of concern, nearly 60 percent of Americans do not read the privacy policies of apps and social media services they use. Most Americans do not have the time or legal expertise to carefully study every privacy policy they encounter. Given that one must accept these terms or not be online, it is simply impractical to expect Americans do so. Yet government agencies assert that it is acceptable to collect and review Americans’ most personal data without a warrant because we have knowingly signed away our rights. There is good news. In the struggle for government surveillance reform currently taking place on Capitol Hill – and the introduction of the Protect Liberty and End Warrantless Surveillance Act – Americans are getting a better understanding of the costs of being treated as digital chattel by data brokers and government. The House Judiciary Committee today announced its long-awaited bill that reauthorizes Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) while reforming provisions that have allowed warrantless spying on Americans by federal agencies.

Enacted in 2008, Section 702 permits the FBI, the CIA, the National Security Agency, and the National Counter Terrorism Center to search through billions of warrantlessly acquired international communications to surveil foreign targets on foreign soil. The emails, texts messages, internet data, and other communications of Americans are also incidentally swept up in this program, allowing agencies to look for specific information about U.S. persons (U.S. citizens and permanent residents) without a warrant, as required by the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Statement of Bob Goodlatte, former Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee and PPSA Senior Policy Advisor: “The House Judiciary Committee has unveiled the most important government surveillance reform measure since the creation of FISA in 1979. “This bill addresses a growing crisis. Our government, with the FBI in the lead, has come to treat Section 702 – enacted by Congress for the surveillance of foreigners on foreign soil – as a domestic surveillance program of Americans. “The government used this authority to conduct over 200,000 ‘backdoor searches’ of Americans in 2022. Section 702 has been used to search the communications of sitting House and Senate Members, protesters across the ideological spectrum, 19,000 donors to a congressional campaign, journalists, and a state court judge. The American people can see that Section 702 has morphed into something that Congress never intended. “The House Judiciary Committee – with the leadership of Chairman Jim Jordan, Ranking Member Jerry Nadler, and Rep. Andy Biggs – has now crafted a bill that restores the rule of law. This bill allows Section 702 to continue to protect Americans by conducting surveillance of foreign spies and terrorists. But it does so in a way that respects the Fourth Amendment. By achieving this balance, the Judiciary Committee’s bill promises to rebuild the trust of the American people in the law, strengthening freedom from unwarranted surveillance and our right to privacy, as well as our national security.” Statement of Gene Schaerr, PPSA general counsel: “The House Judiciary Committee bill brings sweeping and needed reforms to Section 702 while respecting the legitimate needs of national security. It addresses the prime problems with this authority, establishing a clear warrant requirement. But it also includes some masterful reforms to practices and programs outside of Section 702 that, if left unaddressed, would merely be used by government agencies to end-run the Section 702 reforms. “The House Judiciary Committee bill, for example, imposes a warrant requirement on the government to access and inspect data scraped from consumer apps and sold to the government by data brokers. Without this fix, the government would continue to have ready access to Americans’ most sensitive information – about our medical issues, our location histories and travels, our financial records, and those with whom we associate for political, religious, or personal reasons. “This bill also puts an amicus, a representative of the public’s interest in privacy, into the secret FISA courtroom to challenge the issuance of warrants when the government exceeds its authority. “For years, champions of the Constitution have had to play a game of whack-a-mole with the surveillance state, closing one surveillance loophole only to find federal agencies easily replacing it by exploiting another. Although it will likely see further improvements in the legislative process, the House Judiciary Committee bill closes most of the big loopholes, forcing federal agencies to respect the Fourth Amendment. “We commend Chairman Jordan, Ranking Member Nadler, and Rep. Biggs for their hard work and wise judgments in crafting a bill that will better protect both our national security and our constitutional rights.” Defenders of the surveillance status quo in Congress are perplexed by the success of reform proposals and are flailing in response. Some have made national media appearances that give the American people an inaccurate picture of how Section 702 works and how the government uses it to access large amounts of Americans’ personal information without a warrant.

One such champion did not do his cause any favors when he made inflammatory statements on Face the Nation on Sunday about the leading Members of Congress who want to bring Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act in line with the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution. We were told that Chairman Jim Jordan and many of his bipartisan colleagues on the House Judiciary Committee want to “hinder” the process of foreign intelligence and “don’t fully understand” Section 702’s “value and importance to national security.” Moreover, Jordan and his colleagues would “foolishly” cut off one of the most important tools for protecting national security. What we didn’t hear was anything about Section 702’s long litany of abuses, or the need to protect the freedoms and privacy of law-abiding Americans from government snooping. Protecting Americans’ rights and upholding the Constitution is a duty of the House Judiciary Committee. With primary jurisdiction over this program, the bipartisan team of reformers on the House Judiciary Committee understand this surveillance program all too well. They are working on a bill that has far greater substance than what Sen. Mike Lee has called the “window dressing” reforms of the House Intelligence Committee bill, the full text of which has yet to be released. It was never explained in this Face the Nation interview that Section 702 – enacted by Congress to authorize surveillance of foreign spies and terrorists on foreign soil – has morphed into a domestic spying program that in recent years has compromised the privacy of Americans millions of times. Add to that the practice of federal agencies buying Americans’ most sensitive and personal information from data brokers and holding and examining it without a warrant, as required by the Constitution, and you have a recipe for a surveillance state. Champions of surveillance are also wrong when they say that the bipartisan team that wants to reform Section 702 are hindering its passage. The bipartisan Judiciary Committee bill will reauthorize Section 702 for the purpose Congress intended – gathering intelligence about noncitizens outside the United States – while imposing a warrant requirement when the government wants to search Section 702-gathered information about American citizens. The Judiciary Committee, with a long history of protecting civil rights, is expected to soon mark up and pass a strong, bipartisan bill that will give federal agencies the tools they need to protect our national security while safeguarding our constitutional rights. A recent opinion-editorial in The Hill casts a harsh light on the unfolding state of “digital authoritarianism” in America’s schools. Public schools are increasingly adopting artificial intelligence to monitor students and shape curricula. This trend could ultimately have the effect of stifling education, invading privacy, and changing the attitude of adult American society about pervasive surveillance.

Civil rights attorney Clarence Okoh writes that “controversial, data-driven technologies are showing up in public schools nationwide at alarming rates.” These technologies include AI-enabled systems such as “facial recognition, predictive policing, geolocation tracking, student device monitoring and even aerial drones.” A report compiled by the Center for Democracy & Technology found that over 88 percent of schools use student device monitoring, 33 percent use facial recognition and 38 percent share student data with law enforcement. These surveillance technologies enable schools to punish students with greater frequency. A study conducted by Johns Hopkins University found that students at high schools with prominent security measures have lower math scores, are less likely to attend college, and are suspended more often compared to students in schools with less surveillance. The study claims to factor out social and economic background data. Okoh highlights a Florida case in which the sheriff’s office has purportedly used a secret predictive policing program against vulnerable schoolchildren. At some point, the punishments of “predictive” behavior could easily become a self-fulfilling prophecy. A group known as the People Against the Surveillance of Children and Overpolicing (PASCO) has found through litigation and open records requests that the Pasco, Florida, sheriff’s office has a secret youth database that contains the names of up to 18,000 children each academic year. According to PASCO, the sheriff’s office built this database using an algorithm that assessed confidential student records: everything from grades, attendance records, and histories of child abuse are used to assess a student’s risk of falling into “a life of crime.” Many programs directly target minority students. Wisconsin uses a dropout prevention algorithm that uses race as a risk factor. Such modeling, mixed with surveillance software in schools, could have a demonstrably harsher impact on minority students, leading to higher suspension rates. State legislators need to drill down into these reports and verify these claims. One avenue to explore is the role of parents in this process. Are they informed of these practices? Have they been sufficiently heard on them? We have sympathy for why some schools would feel the need to resort to such tactics. But if these facts pan out, then artificial intelligence has just opened up a new front – not just in the war on privacy, but one that could seal the fate of children’s future lives. It also could have an impact on adult society as well. An elementary school student might not understand what it means to be surveilled 24/7 and could become accustomed to it over time. This could lead to a generation of Americans who are inured to ever-present monitoring. If digital authoritarianism becomes the norm in school, it will soon become the norm in society. PPSA looks forward to further developments in this story. When Richard Nixon wanted his minions to run a super-secret surveillance operation that came to be known as the White House Plumbers, the president had it set up in Room 16 in the basement of the Executive Office Building. A recent White House memo obtained and reported by Wired shows that a massive dragnet surveillance program – warrantlessly scooping up phone records from Americans by the trillions – is now being run out of the White House today.

This program, currently called Data Analytical Services (DAS) allows federal, state, and local law enforcement to mine the details, though not the content, of Americans’ calls. As a study at Stanford University showed, metadata alone can reveal startling amounts of highly personal information. When the government adds “chain analysis” – moving outward from one target to the person he or she communicated with, and on to the next person – vast networks of associational groups, whether religious, political, or journalistic, can be X-rayed. “In response to a 2019 Freedom of Information Act request the Project for Privacy and Surveillance Accountability filed jointly with Demand Progress, we received a document from the Drug Enforcement Administration with a redaction into which one could easily fit the word ‘Hemisphere’” said Gene Schaerr, PPSA general counsel. “Hemisphere was the name of this warrantless surveillance program until it was rebranded as Data Analytical Services. Clearly, the government was holding on to something it didn’t want us to see. We had no idea, however, they were hiding it in the White House. With the ‘two-hop’ rule, government at all levels can not only target an individual, but also her spouse, children, parents, and friends. “This is nothing less than warrantless, dragnet surveillance at the national level,” Schaerr said. There is as of yet no evidence that implicates this program in political surveillance. But as with the Nixon Administration, running a program out of the White House has unique advantages. In the current era, a White House operation is not subject to the requirement to review its privacy impacts. It also cannot be subject to FOIA requests. Wired reports that the memo shows that over the years the White House has provided more than $6 million to target the records of any calls that cross AT&T’s infrastructure. Wired also reports that White House funding had intermittent starts and cancellations under the current and last two presidents. Still, the program seems to have been in continuous operation for over a decade. Internal records suggest that the government can access records held by AT&T for at least ten years. These records include the names of callers and recipients, the dates and times of their calls, and their location histories, although the 2018 Supreme Court opinion, Carpenter v. United States, established a warrant requirement for location data. On Sunday, Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR) fired off a letter to Attorney General Merrick Garland saying, “I have serious concerns about the legality of this surveillance program, and the materials provided by the DOJ contain troubling information that would justifiably outrage many Americans and other Members of Congress.” This breaking news story is certain to provide more momentum for the Government Surveillance Reform Act (GSRA), and the inclusion of a broad warrant requirement and other reforms within a House Judiciary Committee reform bill now being drafted. As this story makes clear, we must have these reforms before any extension of Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act can be contemplated. Every now and then, even with an outlook jaded by knowledge of the many ways we can be surveilled, we come across some new outrage and find ourselves shouting – “no, wait, they’re doing what?”

The final dismissal of a class-action lawsuit law by a federal judge in Seattle on Tuesday reveals a precise and disturbing way in which our cars are spying on us. Cars hold the contents of our texts messages and phone call records in a way that can be retrieved by the government but not by us. The judge in this case ruled that Honda, Toyota, Volkswagen, and General Motors did not meet the necessary threshold to be held in violation of a Washington State privacy law. The claim was that the onboard entertainment system in these vehicles record and intercept customers’ private text messages and mobile phone call logs. The class-action failed because the Washington Privacy Act’s standard requires a plaintiff to approve that “his or her business, his or her person, or his or her reputation” has been threatened. What emerged from this loss in court is still alarming. Software in cars made by Maryland-based Berla Corp. (slogan: “Staggering Amounts of Data. Endless Possibilities”) allows messages to be downloaded but makes it impossible for vehicle owners to access their communications and call logs. Law enforcement, however, can gain ready access to our data, while car manufacturers make extra money selling our data to advertisers. This brings to mind legislation proposed in 2021 by Sens. Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Cynthia Lummis (R-WY) along with Reps. Peter Meijer (R-MI) and Ro Khanna (D-CA). Under their proposal, law enforcement would have to obtain a warrant based on probable cause before searching data from any vehicle that does not require a commercial driver’s license. Under the “Closing the Warrantless Digital Car Search Loophole Act,” any vehicle data obtained in violation of this law would be inadmissible in court. Sen. Wyden in a statement at the time said: “Americans’ Fourth Amendment rights shouldn’t disappear just because they’ve stepped into a car.” They shouldn’t. But as this federal judge made clear, they do. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in March issued a controversial opinion in Twitter v. Garland that the Electronic Frontier Foundation calls “a new low in judicial deference to classification and national security, even against the nearly inviolable First Amendment right to be free of prior restraints against speech.”

X (née Twitter) is appealing this opinion before the U.S. Supreme Court. Whatever you think of X or Elon Musk, this case is an important inflection point for free speech and government surveillance accountability. Among many under-acknowledged aspects of our national security apparatus is the regularity with which the government – through FBI national security letters and secretive FISA orders – demands customer information from online platforms like Facebook and X. In 2014, Twitter sought to publish a report documenting the number of surveillance requests it received from the government the prior year. It was a commendable effort from a private actor to provide a limited measure of transparency in government monitoring of its customers, offering some much-needed public oversight in the process. The FBI and DOJ, of course, denied Twitter’s efforts, and over the past ten years the company has kept up the fight, continuing under its new ownership. At issue is X’s desire to publish the total number of surveillance requests it receives, omitting any identifying details about the targets of those requests. This purpose is noble. It would provide users an important metric in surveillance trends not found in the annual Statistical Transparency Report of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. Nevertheless, in April 2020, a federal district court ruled against the company’s efforts at transparency. In March 2023, the Ninth Circuit upheld the lower court’s ruling, sweeping away a substantial body of prior restraint precedent in the process. Specifically, the Ninth Circuit carved out a novel exemption to long established prior restraint limitations: “government restrictions on the disclosure of information transmitted confidentially as part of a legitimate government process.” The implications of this new category of censorable speech are incalculable. To quote the EFF amicus brief: “The consequences of the lower court’s decision are severe and far-reaching. It carves out, for the first time, a whole category of prior restraints that receive no more scrutiny than subsequent punishments for speech—expanding officials’ power to gag virtually anyone who interacts with a government agency and wishes to speak publicly about that interaction.” This is an existential speech issue, far beyond concerns of party or politics. If the ruling is allowed to stand, it sets up a convenient standard for the government to significantly expand its censorship of speech – whether of the left, right or center. Again, quoting EFF, “[i]ndividuals who had interactions with law enforcement or border officials—such as someone being interviewed as a witness to a crime or someone subjected to police misconduct—could be barred from telling their family or going to the press.” Moreover, the ruling is totally incongruous with a body of law that goes back a century. Prior restraints on speech are the most disfavored of speech restrictions because they freeze speech in its entirety (rather than subsequently punishing it). As such, prior restraint is typically subject to the most exacting level of judicial scrutiny. Yet the Ninth Circuit applied a lower level of strict scrutiny, while entirely ignoring the procedural protections typically afforded to plaintiffs in prior restraint cases. As such, the “decision enables the government to unilaterally impose prior restraints on speech about matters of public concern, while restricting recipients’ ability to meaningfully test these gag orders in court.” We stand with X and EFF in urging the Supreme Court to promptly address this alarming development. The Government Surveillance Reform Act (GSRA) Four bipartisan champions of civil liberties – Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR), Sen. Mike Lee (R-UT), Rep. Warren Davidson (R-OH) and Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-CA) – today introduced the Government Surveillance Reform Act (GSRA), legislation that restores force to overused Capitol Hill adjectives like “landmark,” “sweeping,” and “comprehensive.”

“The Government Surveillance Reform Act is ambitious in scope, thoughtful in its details, and wide-ranging in its application,” said Bob Goodlatte, former Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee and PPSA’s Senior Policy Advisor. “The GSRA is a once-in-a-generation opportunity for wide-ranging reform.” The GSRA curbs the warrantless surveillance of Americans by federal agencies, while restoring the principles of the Fourth Amendment and the policies that underlie it. The authors of this bill set out to achieve this goal by reforming how the government uses three mechanisms to surveil the American people.

The GSRA will rein in this ballooning surveillance system in many ways.

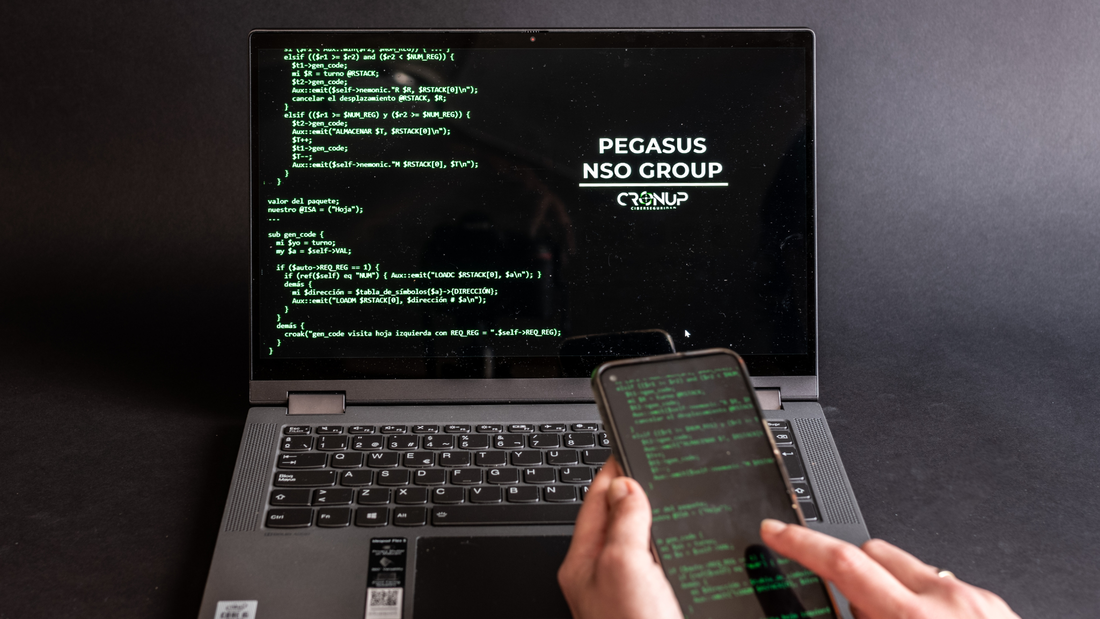

“The GSRA enjoys widespread bipartisan support because it represents the most balanced and comprehensive surveillance reform bill in 45 years,” Goodlatte said. “PPSA joins with a wide-ranging coalition of civil liberties organizations to urge Congress to make the most of this rare opportunity to put guardrails on federal surveillance of Americans. “We commend Senators Wyden and Lee, and Representatives Davidson and Lofgren, for writing such a thorough and precise bill in the protection of the constitutional rights of every American.” Apple Sends Notice of Hack Pegasus – the Israeli-made spyware – continues to proliferate and enable bad actors to persecute journalists, dissidents, opposition politicians, and crime victims around the world.

This spyware transforms a smartphone into the surveillance equivalent of a Swiss Army knife. Pegasus has a “zero-day” capability, able to infiltrate any Apple or Android phone remotely, without requiring the users to fall for a phishing scam or click on some other trick. Once uploaded, Pegasus turns the victim’s camera and microphone into a 24/7 surveillance device, while also hoovering up every bit of data that passes through the device – from location histories to text, email, and phone messages. We’ve written about how Mexican cartels have used Pegasus to track down and murder journalists. We’ve covered the role of Pegasus in the murder of Saudi dissident Adnan Khashoggi, and how an African government used it to spy on an American woman while she was receiving a briefing inside a State Department facility on her father’s abduction. Now fresh evidence from Apple alerts shows how Pegasus continues to be used by governments to spy on political opponents. Journalists have learned that the Israeli-based NSO Group has sold its spyware to at least 10 governments. Two years ago, it was revealed that a government had used Pegasus to surveil Spanish politicians, including the prime minister, as well as regional politicians. Now it is happening in India. On Oct. 31, just in time for Halloween, Apple sent notices to more than 20 prominent journalists, think tank officials, and politicians in opposition to Prime Minster Narenda Modi that hacking attempts had been made on their smartphones. In 2021, The Washington Post and other media organizations investigated a list obtained by Forbidden Stories, a Paris-based non-profit media outlet, tracking down more than 1,000 phone numbers of hundreds of prominent Indians who were set to be surveilled by Pegasus. This plan now seems to have been executed, at least in part. “Spyware technology has been used to clamp down on human rights and stifle freedom of assembly and expression,” said Likhita Banerj of Amnesty International. “In this atmosphere, the reports of prominent journalists and opposition leaders receiving the Apple notifications are particularly concerning in the months leading up to state and national elections.” Yesterday Spain, today India, tomorrow the United States? It is public knowledge that the FBI owns a copy of Pegasus and that a recent high-level government attorney from the intelligence community has signed on to represent the NSO Group. This is all the more reason for Congress to pass serious reforms to Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, to curtail all forms of illicit government surveillance of Americans. PPSA will continue to monitor this story. When FBI Director Christopher Wray came under heated questioning during his testimony Tuesday before the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, he let slip a remark likely to haunt him for the rest of the debate over proposed reforms to Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA).

Director Wray said, “With everything going on in the world, imagine if a foreign terrorist overseas directs an operative to carry out an attack here on our own backyard, but we’re not able to disrupt it because the FBI’s authorities have been so watered down.” By “watered down” Wray meant reformers’ proposal requiring the FBI to meet the Fourth Amendment’s requirement to obtain a probable cause warrant before accessing the private communications of Americans taken from Section 702. This authority was enacted by Congress to enable surveillance of foreign terrorists and spies located on foreign soil. There is no reason why Section 702 cannot be used to surveil “a foreign terrorist overseas.” The problem is that this authority has become a prime resource for the FBI and other agencies to warrantlessly review the information of Americans. Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY), Ranking Member on the committee, responded: “You would think we’d be going after foreigners, but we are using the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act to go after Americans.” In addition to skepticism from Sen. Paul and others on the committee, Director Wray’s assertions are contradicted by others with experience in FISA. In a recent editorial, Sharon Bradford Franklin, chair of the independent government watchdog group, the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board (PCLOB), with two other board members in a recent Washington Times editorial, supported requiring a court order or warrant before the government can review Americans’ Section 702 data. The PCLOB members noted that “the FBI has repeatedly violated querying rules to run searches on Americans. This includes impermissible searches for members of Congress, those who protested the murder of George Floyd, preachers, participants in an FBI community relations program, victims who reported crimes …The FBI has failed to get this right for more than a decade. The bureau’s persistent noncompliance over the years dramatically illustrates the need for independent, impartial, and external review. These compliance errors may also undermine the public’s trust in the FBI, raising real questions about its ability to police itself.” In his written testimony, Director Wray also informed the committee that a warrant requirement would amount to a “de facto ban” on U.S. person queries because warrants are so difficult to obtain from a court. Would a warrant requirement necessarily be a “ban” that would “water down” the FBI’s ability to protect Americans? David Aaron, who held several senior legal positions at the Department of Justice’s National Security Division, wrote in Just Security that “requiring the government to establish probable cause and obtain judicial approval before searching for U.S. person’s communications within previously collected material would bolster that confidence and is a relatively light burden on the government.” A majority in Congress clearly agree. None other than Senate Judiciary Chairman Dick Durbin (D-IL) has said he will only support Section 702 reauthorization if there are “significant reforms,” including “first and foremost, addressing the warrantless surveillance of Americans in violation of the Fourth Amendment.” Or, as Chair Franklin and her colleagues wrote: “We do not permit the police to break into a home without such court approval, and we should not permit government personnel to access our communications through U.S. person queries without court review. This is Civics 101.” Sen. Paul told Wray: ”I fear that our federal government is still undertaking many of the same tactics that the Church Committee found to be unworthy of democracy.” Perhaps it is the Fourth Amendment that has been watered down. Is the Executive Branch Targeting Oversight Committees? PPSA continues to press a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request seeking documents that would shed light on the extent to which the executive branch is spying on Members of Congress. We are asking the government for production of documents on “unmasking” and other forms of government surveillance of 48 current and former House and Senate Members on committees that oversee the intelligence community.

Now the court and Congress have fresh reason to give the issue of executive branch spying on Congress and its oversight committees renewed attention. Jason Foster, the former chief investigative counsel for Sen. Chuck Grassley – the Ranking Member of the Senate Judiciary Committee – recently learned that he is among numerous staffers, Democrats as well as Republicans, who had their personal phone and email records searched by the Department of Justice in 2017. A FOIA request filed by the nonprofit Empower Oversight, founded by Foster, seeks documents concerning the government’s reasons for compelling Google to reveal the names, addresses, local and long-distance telephone records, text message logs and other information about the accounts of congressional attorneys who worked for committees that oversee DOJ. The government’s subpoena also compelled the release of records indicating with whom each user was communicating. The Empower Oversight FOIA notes: “This raises serious public interest questions about the basis of such intrusion into the personal communications of attorneys advising congressional committees conducting oversight of the Department. Constitutional separation of powers and privilege issues raised by the Speech or Debate Clause of (U.S. Const. art I. § 6) and attorney-client communications of those targeted with these subpoenas should have triggered requirements for enhanced procedural protections and approvals.” As The Wall Street Journal noted in an editorial, these subpoenas coincided with leaks of classified information concerning a wiretapped phone call between incoming Trump national security adviser Michael Flynn and the Russian ambassador. This leak was investigated by the Senate Judiciary Committee. Many now wonder if DOJ’s dragnet of personal information of congressional staffers was an attempt at misdirection, perhaps a fishing expedition to find someone else to blame. Empower Oversight’s FOIA states: “If the only reason the Justice Department targeted the communications of these congressional attorneys was their access to classified information that was later published by the media, it raises the question of whether the Department also subpoenaed the personal phone and email records of every Executive Branch official who had access to the same information.” The Empower Oversight FOIA concludes about this surveillance of Congressional staff: “It begs the question whether DOJ was equally zealous in seeking the communications records of its own employees with access to any leaked document.” Sen. Grassley, who aggressively pursues government surveillance overreach, will likely want to follow up on these questions. In the meantime, PPSA petitions the D.C. Circuit Court for an en banc hearing on the possible unmasking and other surveillance of some of the elected bosses of these congressional attorneys. The Congressional debate over the reauthorization of Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) has mostly centered around the outrage of federal agencies using an authority meant for the surveillance of foreigners on foreign soil to warrantlessly collect the communications of hundreds of thousands of Americans every year.

But the Section 702 debate highlights an even greater outrage that needs to be addressed – the routine practice by federal agencies to purchase and access the private data of Americans scraped from our apps and devices without a warrant. While federal data purchases are not part of Section 702, history suggests that any reforms made to Section 702 to curtail the surveillance on Americans in the pool of “incidentally” collected communications will be futile if we don’t close this other loophole. Our data, freely collected and reviewed at will by the government, can be more personal than a diary – detailing our medical concerns, romantic lives, our daily movements, whom we associate with, our politics and religious beliefs. The Wall Street Journal shined a much-needed light on this practice. It reported on the relationship between U.S. government agencies and the shadowy world of data-broker middlemen who peddle our most sensitive personal information. The Journal reported that India-based Near Intelligence has been “surreptitiously obtaining data from numerous advertising exchanges” and selling this data to the NSA, Joint Special Operations Command, the Department of Defense, and U.S. Air Force Cyber Ops. The Journal accessed a memo from Jay Angelo, Near Intelligence general counsel and chief privacy officer, to CEO Anil Mathews about three privacy problems. First, Angelo wrote that Near Intelligence sells “geolocation data for which we do not have consent to do so.” Second, he wrote the company sells or shares “device ID data for which we do not have consent to do so.” And, finally, Angelo wrote, the company violates the privacy laws of Europe by selling Europeans’ data outside of Europe. Customers include agencies of the U.S. federal government, which “gets our illegal EU data twice per day.” It is unclear the extent to which this company sells Americans’ data, though it seems likely that the privacy of Americans is implicated given that the company boasts of having access to data from a billion devices. Near Intelligence is just one actor in this shadowy world of merchants of personal data. Congress should require government agencies to obtain a probable cause warrant to examine the private data of Americans, whether collected under Section 702 or through data purchases. The titles slapped on government reports are often meant to downplay or obfuscate. Not so the title of a report from the Inspector General of the Department of Homeland Security – CBP, ICE, and Secret Service Did Not Adhere to Privacy Policies or Develop Sufficient Policies Before Procuring and Using Commercial Telemetry Data.

The title may be lengthy, but it describes the alarming extent of lawless surveillance by federal agencies. For years, these three agencies freely accessed Americans’ location histories and other data collected from mobile device applications and sold by third-party data vendors to the government. The Department of Homeland Security Privacy Office itself “did not follow or enforce its own privacy policies and guidance.” The report notes that DHS itself has no department-wide policy regarding privacy. This negligence allowed DHS agencies to break the law and do so without any supervisory review. The law in this case is the E-Government Act of 2002, in which Congress mandated that agencies conduct a Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA) that requires the government to spell out what information it is collecting, why it is collecting it, how that information will be used, stored, and shared. The law also requires agencies to describe how this information will be protected from unauthorized use or disclosure, and how long it will be retained. Instead, CBP, ICE, and the Secret Service helped themselves to location data harvested from apps installed on Americans’ smartphones. One CBP official felt sufficiently comfortable with this technology to use it to track his coworkers’ daily movements, for what purpose only HR knows. Why might have DHS leaned away from adhering to the law? Nate Wessler, deputy project director of ACLU’s Speech, Privacy and Technology project told 404 Media that if the agencies had performed the required Privacy Impact Assessments “they could have reached only one reasonable conclusion: the privacy impact is extreme.” The unclassified DHS report is a thunderclap of candid accounting of government agencies bending or breaking the law. It follows the unsparing analysis of the Crossfire Hurricane investigation by the 2019 Department of Justice Inspector General and PCLOB’s recent analysis of Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, advocating for greater judicial oversight of that program’s use of Americans’ communication “incidentally” caught up in surveillance of foreign targets. The DHS report should especially be read in the light of a surprisingly frank report released by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence that commercially acquired data can be used to follow protestors, degrade First Amendment expression, and “facilitate blackmail, stalking, harassment, and public shaming.” The DHS report is just one more reason why Congress should take the pending reauthorization of Section 702 as a once-in-a-generation opportunity for reform. Congress should require federal agencies to obtain a probable cause warrant before examining Americans’ communications and data, whether obtained from Section 702 or through data purchases. Myths vs. Facts: Has the FBI Fixed What Is Wrong with Section 702 with Internal Procedures?10/10/2023

Intelligence Community MYTH: The FBI has new minimization procedures that have dramatically reduced the numbers of U.S. person queries in the Section 702 database and the potential for violations. No fixes in the law are needed.

FACT: Even FBI Director Christopher Wray’s brag that refinements in internal procedures have reduced the number of warrantless searches for Americans’ communications to approximately 204,000 queries of Americans’ personal communications per year is alarming. The number of people who have been victimized by these civil rights violations is equal to the population of many medium-sized U.S. cities. As Sen. Mike Lee says, “That number should be zero. Every ‘non-compliant’ search violates an American’s constitutional rights.” Jonathan Turley of the George Washington University Law School dismissed the FBI’s recent boasts about the reduced number of improper queries into Americans’ private information, likening that boast to “a bank robber saying we’re hitting smaller banks.” The many broken promises of the FBI should leave the bureau with little room for a “trust me” clean reauthorization of Section 702. Consider the government’s long history of abuses. In just the last few years, in violation of its own rules:

Other actions outside Section 702, such as the wide-ranging politically motivated investigation of “radical traditional Catholics,” further reveal an FBI appetite for playing politics. Nobody in their right mind should want the FBI to have warrantless access to their private sensitive personal communications and data. Congress passed a mandate in 2021 that will require all new cars sold later in this decade to have a built-in drunk driver detection system. This law, well-intentioned as it may be, is fraught with enormous risks to the privacy of any American who drives a car.

The vague goal this mandate sets out is: If your car thinks you’re overserved, your car won’t start. Or perhaps it will pull over and call the police. It is not clear, exactly, how this technology will work. In any event, this law promises to make every car a patrol car, with you inside it. Rep. Thomas Massie (R-KY), a long-time defender of civil liberties, is not having it. He is proposing an amendment to the Transportation, Housing and Urban Development (yes, the Washington acronym here is THUD) appropriations bill to safeguard Americans’ constitutional right to privacy by forbidding federal expenditures to implement this ill-conceived mandate. PPSA is proud to support this amendment and we stand together with other supporters, including FreedomWorks and the Due Process Institute. While aggressive action to curb impaired driving is appropriate, the privacy issues raised by Rep. Massie about the mandate for this “advanced drunk driving and impaired driving prevention technology” are impossible to ignore. They are ultimately of great consequence to the future of our country. First, consider that this technology will monitor the driving performance of millions of Americans who don’t drink and drive, potentially keeping many of them from operating their vehicles. While many states allow for court-mandated ignition interlock devices for people convicted of DUIs (requiring people under such an order to clear a self-administered breathalyzer test before their cars will start), these state restrictions are far more reasonably tailored than the broader and more intrusive federal mandate. Crucially, they make the necessary distinction between the irresponsible few who are under a court order, and the responsible many who are not. Additionally, the state regulations do not passively monitor drivers’ performance. What do the responsible many have to lose under the federal mandate? The driver detection mandate could violate your privacy and constitutional rights on a massive scale. Consider: Absent a breathalyzer, this technology might well – like some commercial delivery operators already do – use a camera and AI to passively monitor your body movements for signs of impairment. Moreover, would your video data be stored? And if it is stored, would camera data follow you and any passengers in the car – perhaps with a sound recording of anything that you might say to each other? (After all, analyzing voice data could be used by AI to look for the possible slurring of your words.) And if this video and/or voice data is stored, would these videos then be part of the enormous stream of data that federal agencies – from the IRS, to the FBI, to the DHS – now routinely purchase and access without a warrant? (This brings to mind an old joke: An FBI agent walks into a bar. The bartender says, “I’ve got a joke for you.” The agent replies, “heard it!”) Video analytics technology, like facial recognition software, is hardly foolproof. Would this yet-to-be-developed device read people with disabilities as being intoxicated? Would perfectly sober people register false positives and not be able to drive? Rep. Massie’s amendment would provide a much-needed sobriety check on the government’s foolhardy leap into mandating this technology. PPSA strongly urges Congress to pass the Massie amendment and protect the privacy and constitutional rights of millions of Americans. Intelligence Community MYTH: Warrantless access to Americans’ data is vital to defending people and companies against cyberattacks and ransomware. Otherwise, we’d be wide-open to cyberattacks from Russia and China.

FACT: Most cybersecurity experts disagree with the government’s argument. The Washington Post conducted a survey of “a group of high-level digital security experts from across government, the private sector and security research community.”

There is no “defensive” exception to the Fourth Amendment. The fact that the government claims to be doing something for our own good does not make it constitutional, nor does it mitigate the privacy intrusion or risk of abuse. If government agents want to access our private communications for our own good, they should simply ask our permission. Without that permission, they should get a probable cause warrant to spy on Americans’ communications. NYPD’s Angwang Case This week, Baimadajie Angwang, an officer of the New York Police Department, appears before an administrative judge to make a bid to remain on the force. The long journey of Angwang – from Tibetan refugee to U.S. Marine in Afghanistan, to police officer, to accused spy – shows how an American can have his reputation destroyed and his freedom threatened by secret charges.

As a teenager, Angwang visited the United States on a cultural exchange program only to be beaten by Chinese police on his return to his homeland. He fled the country and successfully sought asylum and citizenship in the United States, serving as a Marine. Angwang joined the NYPD in 2016, married, and became a father. On the morning of Sept. 21, 2020, Officer Angwang was confronted in front of his home by four souped-up pickup trucks squealing to a halt, half-a-dozen officers in tactical gear piling out, and rifles pointed inches from his face. Angwang was charged with spying for China on his fellow Tibetans in New York and lying on a security form. Angwang was held in the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn for five months. The conditions in that jail are wretched, far worse than those of most prisons. Angwang had to borrow underwear from another prisoner. The facility lost power, leaving desperate prisoners to suffer in the cold through a bitter January. When Angwang fell ill, guards ignored his pleas for help. What was Angwang’s alleged crime? It grew out of his quest to secure a long-term visa from the Chinese consulate to visit his elderly parents in Tibet and allow them to meet their granddaughter. In extensive conversations with a consular official, Angwang had tried to get this visa by demonstrating that he was friendly and apolitical. Angwang’s lawyer, John F. Carman, wrote to a federal judge that his client tried to strike a “solicitous tone and accommodating posture.” Prosecutors said that Angwang invited Chinese consular officials to NYPD events and reported on the activities of other Tibetans in New York. The prosecution’s case was based on calls and likely texts between Angwang and the consulate, all secretly recorded. To be fair, the government arguably has good reason to watch how Chinese diplomats try to convert American citizens into spies. Furthermore, the government did obtain a warrant to surveil Angwang. Carman said that evidence from these communications, however, was misinterpreted and taken out of context by prosecutors. In court, Angwang faced a dilemma shared with many charged with evidence they are not allowed to see. In such cases, when classified evidence is introduced in a trial, the judge and prosecutors secretly determine in a sealed court what evidence can be seen by the defense attorney and what can be presented in court. In August 2022, Carman read a single-page summary of these charges in the prosecutor’s office. “What I saw was so powerful, it caused me to write the judge and ask if that’s what they have, why hasn’t there been a motion to dismiss?” Carman told The New York Times. In January, prosecutors dropped the case, citing a “holistic” assessment of the evidence and “additional information bearing on the charges.” Now Angwang is asking an administrative court to let him keep his job as a New York City police officer. If he loses his job, Angwang will have to seek another job with a resume and a reputation forever under the shadow of secret evidence. “It creates a cloud of mystery,” Carman said. “You only have to assume that this guy did stuff that was bad for the country. Which is an inference that’s easily drawn, but in this case should not have been drawn.” And should a defendant like Angwang, who escapes the crosshairs of secret evidence, sue the government for compensation, the state secrets privilege will ensure that he cannot win. The evidence against the government, you see, must remain secret. The defamatory effect, however, lives on. Is there really a good justification – the protection of sources and methods – for withholding so much of a secret case? Can the government at least issue a note of exoneration for Angwang and others when secret charges are dropped? PCLOB Chair Ups Ante by Calling for Probable Cause Warrant for U.S. Person Queries What are the topline takeaways from the report from the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board (PCLOB) on Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA)?

A majority of board members of this government watchdog panel directly counter the claims of the Biden Administration and the intelligence community that a requirement for the government to seek judicial review of the private communications of Americans would be “operationally unworkable” and lead to extreme danger to national security. The report punctures the FBI’s frequent claims that having the ability to rifle through Americans’ communications without a warrant is essential to national security and protecting the United States from harm. The PCLOB majority endorses “individualized and particularized judicial review” by the FISA Court before the government can review data of U.S. citizens and legal residents. PCLOB is coming down firmly on the side of civil liberties organizations that have long argued against intelligence and law enforcement agencies being allowed to have ready access to Americans’ private data and communications, with little judicial oversight. Internal FBI Procedures Insufficient The PCLOB majority finds the internal changes by the FBI in its Section 702 procedures to be far less than what is needed to protect Americans from backdoor searches, the practice of using secretly derived information to develop a case. Moreover, these searches are generally useless, as are the FBI’s internal procedures. The report also rejects that broad categories of searches, such as so-called “defensive” searches for potential victims’ information, should be exempted from judicial review. Amici, Abouts and Unmasking The report endorses the proposal to require amici – or qualified civil liberties experts to advise the FISA Court whenever proposed investigations touch sensitive cases that implicate basic constitutional rights. The board would narrow the standards by which the government selects targets. And the board would formally restrict “abouts” collection – information in which a target is merely mentioned. Even the two board members who voted against the report found that “The U.S. Intelligence Community should adopt new rules to protect against the unmasking of U.S. Persons for political purposes.” The Chair’s Call for a Warrant Requirement Chair Sharon Bradford Franklin (see p. 226) writes that a “search through Section 702 communications data seeking information about a particular American constitutes a search under the Fourth Amendment, and current query standards are insufficient to meet constitutional requirements.” Chair Franklin notes that the FBI routinely runs searches of U.S. persons at a preliminary stages of an inquiry. The FBI “asserted that it could not meet a probable cause standard for such queries conducted at these early stages.” Nor could the FBI identify, outside the categories of “victim” or “defensive” queries, “a single criminal prosecution that relied on evidence identified through a U.S. person query.” Chair Franklin raises the ante on PCLOB’s recommendation that a FISA Court provide judicial review for U.S. person queries. “But I believe that Congress should also require a probable cause standard for FBI’s U.S. person queries conducted at least in part to seek evidence of a crime in order to fully protect Americans’ privacy and civil liberties.” Franklin writes that this is the only way to ensure such queries fully comply with the Fourth Amendment, while being consistent with criminal law in other contexts. She would explicitly adopt the standards of Carpenter v. United States (2018), in which the U.S. Supreme Court held that the police don’t need a warrant to seize a cellphone but do need a warrant to search the contents of that cellphone, which contain “the privacies of life.” She analogizes this case to the “seizure” of the incidental collection of Americans’ information under Section 702, and the need to have a warrant to search it. Chair Franklin’s conclusions, and the PCLOB’s full list of 19 recommendations, are included in the executive summary of its report. |

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed