|

Wired reports that police in northern California asked Parabon NanoLabs to run a DNA sample from a cold case murder scene to identify the culprit. Police have often run DNA against the vast database of genealogical tests, cracking cold cases like the Golden State Killer, who murdered at least 13 people.

But what Parabon NanoLabs did for the police in this case was something entirely different. The company produced a 3D rendering of a “predicted face” based on the genetic instructions encoded in the sample’s DNA. The police then ran it against facial recognition software to look for a match. Scientists are skeptical that this is an effective tool given that Parabon’s methods have not been peer-reviewed. Even the company’s director of bioinformatics, Ellen Greytak, told Wired that such face predictions are closer in accuracy to a witness description rather than the exact replica of a face. With the DNA being merely suggestive – Greytak jokes that “my phenotyping can tell you if your suspect has blue eyes, but my genealogist can tell you the guy’s address” – the potential for false positives is enormous. Police multiply that risk when they run a predicted face through the vast database of facial recognition technology (FRT) algorithms, technology that itself is far from perfect. Despite cautionary language from technology producers and instructions from police departments, many detectives persist in mistakenly believing that FRT returns matches. Instead, it produces possible candidate matches arranged in the order of a “similarity score.” FRT is also better with some types of faces than others. It is up to 100 times more likely to misidentify Asian and Black people than white men. The American Civil Liberties Union, in a thorough 35-page comment to the federal government on FRT, biometric technologies, and predictive algorithms, noted that defects in FRT are likely to multiply when police take a low-quality image and try to brighten it, or reduce pixelation, or otherwise enhance the image. We can only imagine the Frankenstein effect of mating a predicted face with FRT. As PPSA previously reported, rights are violated when police take a facial match not as a clue, but as evidence. This is what happened when Porcha Woodruff, a 32-year-old Black woman and nursing student in Detroit, was arrested on her doorstep while her children cried. Eight months pregnant, she was told by police that she had committed recent carjackings and robberies – even though the woman committing the crimes in the images was not visibly pregnant. Woodruff went into contractions while still in jail. In another case, local police executed a warrant by arresting a Georgia man at his home for a crime committed in Louisiana, even though the arrestee had never set foot in Louisiana. The only explanation for such arrests is sheer laziness, stupidity, or both on the part of the police. As ACLU documents, facial recognition forms warn detectives that a match “should only be considered an investigative lead. Further investigation is needed to confirm a match through other investigative corroborated information and/or evidence. INVESTIGATIVE LEAD, NOT PROBABLE CAUSE TO MAKE AN ARREST.” In the arrests made in Detroit and Georgia, police had not performed any of the rudimentary investigative steps that would have immediately revealed that the person they were investigating was innocent. Carjacking and violent robberies are not typically undertaken by women on the verge of giving birth. The potential for replicating error in the courtroom would be multiplied by showing a predicted face to an eyewitness. If a witness is shown a predicted face, that could easily influence the witness’s memory when presented with a line-up. We understand that an investigation might benefit from knowing that DNA reveals that a perp has blue eyes, allowing investigators to rule out all brown- and green-eyed suspects. But a predicted face should not be enough to search through a database of innocent people. In fact, any searches of facial recognition databases should require a warrant. As technology continues to push the boundaries, states need to develop clear procedural guidelines and warrant requirements that protect constituents’ constitutional rights. While Congress is locked in spirited debate over the limits of surveillance in America, large technology companies are responding to growing consumer concerns about privacy by reducing government’s warrantless access to data.

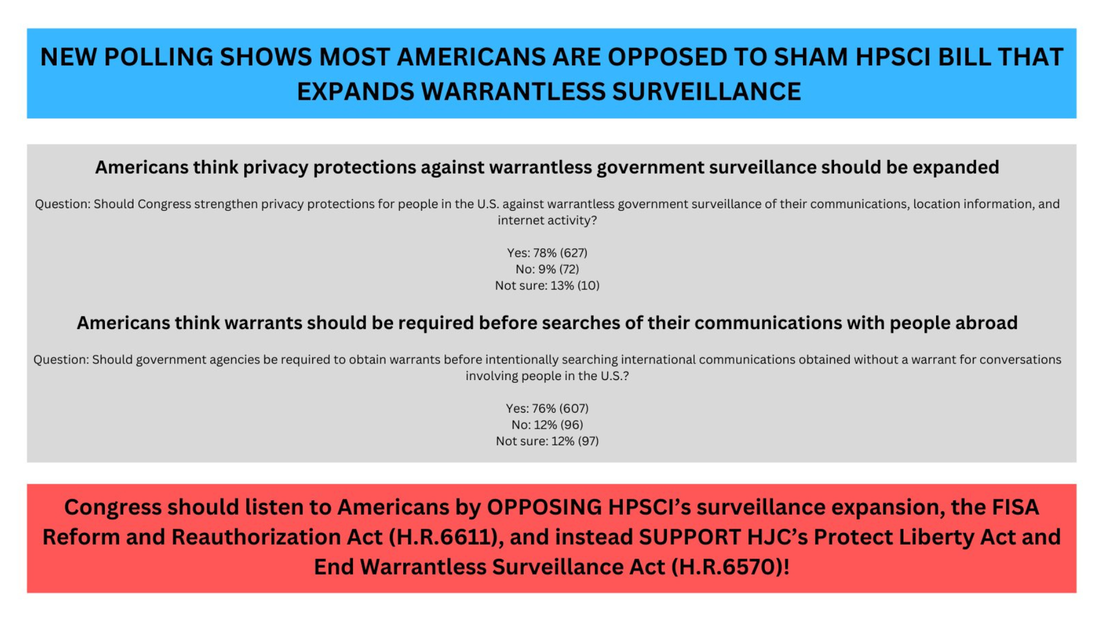

For years, police had a free hand in requesting from Google the location histories of groups of people in a given vicinity recorded on Google Maps. Last month, Google altered the Location History feature on Google Maps. For users who enable this feature to track where they’ve been, their location histories will now be saved on their smartphone or other devices, not on Google servers. As a result of this change, Google will be unable to respond to geofenced warrants. “Your location information is personal,” Google announced. “We’re committed to keeping it safe, private and in your control.” This week, Amazon followed Google’s lead by disabling its Request for Access tool, a feature that facilitated requests from law enforcement to ask Ring camera owners to give up video of goings on in the neighborhood. We reported three years ago that Amazon had cooperative agreements with more than 2,000 police and fire departments to solicit Ring videos for neighborhood surveillance from customers. By clicking off Request for Access, Amazon is now closing the channel for law enforcement to ask Ring customers to volunteer footage about their neighbors. PPSA commends Google and Amazon for taking these steps. But they wouldn’t have made these changes if consumers weren’t clamoring for a restoration of the expectation of privacy. These changes are a sure sign that the mounting complaints of civil liberties advocates are moving the needle of public opinion. Corporations are exquisitely attuned to consumer attitudes, and so they are listening and acting. In the wake of Thursday’s revelation that the National Security Agency is buying Americans’ location data, we urge Congress to show similar sensitivity. With polls showing that nearly four out of five Americans support strong surveillance reform, Congress should respond to public opinion by passing The Protect Liberty Act, which imposes a warrant requirement on all personal information purchased by government agencies. Late last year, Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR) put a hold on the appointment of Lt. Gen. Timothy Haugh to replace outgoing National Security Agency director Gen. Paul Nakasone. Late Thursday, Sen. Wyden’s pressure campaign yielded a stark result – a frank admission from Gen. Nakasone that, as long suspected, the NSA purchases Americans’ sensitive, personal online activities from commercial data brokers.

The NSA admitted it buys netflow data, which records connections between computers and servers. Even without the revelation of messages’ contents, such tracking can be extremely personal. A Stanford University study of telephone metadata showed that a person’s calls and texts can reveal connections to sensitive life issues, from Alcoholics Anonymous to abortion clinics, gun stores, mental and health issues including sexually transmitted disease clinics, and connections to faith organizations. Gen. Nakasone’s letter to Sen. Wyden states that NSA works to minimize the collection of such information. He writes that NSA does not buy location information from phones inside the United States, or purchase the voluminous information collected by our increasingly data-hungry automobiles. It would be a mistake, however, to interpret NSA’s internal restrictions too broadly. While NSA is generally the source for signals intelligence for the other agencies, the FBI, IRS, and the Department of Homeland Security are known to make their own data purchases. In 2020, PPSA reported on the Pentagon purchasing data from Muslim dating and prayer apps. In 2021, Sen. Wyden revealed that the Defense Intelligence Agency was purchasing Americans’ location data from our smartphones without a warrant. How much data, and what kinds of data, are purchased by the FBI is not clear. Sen. Wyden did succeed in a hearing last March in prompting FBI Director Christopher Wray to admit that the FBI had, in some period in the recent past, purchased location data from Americans’ smartphones without a warrant. Despite a U.S. Supreme Court opinion, Carpenter (2018), which held that the U.S. Constitution requires a warrant for the government to compel telecom companies to turn over Americans’ location data, federal agencies maintain that the Carpenter standard does not curb their ability to purchase commercially available digital information. In a press statement, Sen. Wyden hammers home the point that a recent Federal Trade Commission order bans X-Mode Social, a data broker, and its successor company, from selling Americans’ location data to government contractors. Another data broker, InMarket Media, must notify customers before it can sell their precise location data to the government. We now have to ask: was Wednesday’s revelation that the Biden Administration is drafting rules to prevent the sale of Americans’ data to hostile foreign governments an attempt by the administration to partly get ahead of a breaking story? For Americans concerned about privacy, the stakes are high. “Geolocation data can reveal not just where a person lives and whom they spend time with but also, for example, which medical treatments they seek and where they worship,” FTC Chair Lina Khan said in a statement. “The FTC’s action against X-Mode makes clear that businesses do not have free license to market and sell Americans’ sensitive location data. By securing a first-ever ban on the use and sale of sensitive location data, the FTC is continuing its critical work to protect Americans from intrusive data brokers and unchecked corporate surveillance.” As Sen. Wyden’s persistent digging reveals more details about government data purchases, Members of Congress are finding all the more reason to pass the Protect Liberty Act, which enforces the Constitution’s Fourth Amendment warrant requirement when the government inspects Americans’ purchased data. This should also put Members of the Senate and House Intelligence Committees on the spot. They should explain to their colleagues and constituents why they’ve done nothing about government purchases of Americans’ data – and why their bills include exactly nothing to protect Americans’ privacy under the Fourth Amendment. More to come … Well, better late than never. Bloomberg reports that the Biden Administration is preparing new rules to direct the U.S. Attorney General and Department of Homeland Security to restrict data transactions that sells our personal information – and even our DNA – to “countries of concern.”

Consider that much of the U.S. healthcare system relies on Chinese companies to sequence patients’ genomes. Under Chinese law, such companies are required to share their data with the government. The Office of the Director of National Intelligence warns that “Losing your DNA is not like losing a credit card. You can order a new credit card, but you cannot replace your DNA. The loss of your DNA not only affects you, but your relatives and, potentially, generations to come.” The order is also expected to crack down on data broker sales that could facilitate espionage or blackmail of key individuals serving in the federal government; it could be used to panic or distract key personnel in the event of a crisis; and collection of data on politicians, journalists, academics, and activists could deepen the impact of influence campaigns across the country. PPSA welcomes the development of this Biden rule. We note, however, that just like China, our own government routinely purchases Americans’ most sensitive and personal information from data brokers. These two issues – foreign access to commercially acquired data, and the access to this same information by the FBI, IRS, Department of Homeland Security, and other agencies – are related but separate issues that need to be addressed separately, the latter in the legislative process. The administration’s position on data purchases is contradictory. The administration also opposes closing the data-broker loophole in the United States. In the Section 702 debate, Biden officials say we would be at a disadvantage against China and other hostile countries that could still purchase Americans’ data. This new Biden Administration effort undercuts its argument. We should not emulate China’s surveillance practices any more than we practice their crackdowns against freedom of speech, religion, and other liberties. Still, this proposed rule against foreign data purchases is a step in the right direction, in itself and for highlighting the dire need for legislation to restrict the U.S. government’s purchase of its own citizens’ data. The Protect Liberty Act, which passed by the House Judiciary Committee by an overwhelming 35-2 vote to reauthorize Section 702, closes this loophole at home just as the Biden Administration seeks to close it abroad. So when the new Biden rule is promulgated, it should serve as a reminder to Congress that we have a problem with privacy at home as well. No sooner did the Protect Liberty and End Warrantless Surveillance Act pass the House Judiciary Committee with overwhelming bipartisan support than the intelligence community began to circulate what Winston Churchill in 1906 politely called “terminological inexactitudes.”

The Protect Liberty Act is a balanced bill that respects the needs of national security while adding a warrant requirement whenever a federal agency inspects the data or communications of an American, as required by the Fourth Amendment. This did not stop defenders of the intelligence community from claiming late last year that Section 702 reforms would harm the ability of the U.S. government to fight fentanyl. This is remarkable, given that the government hasn’t cited a single instance in which warrantless searches of Americans’ communications proved useful in combating the fentanyl trade. Nothing in the bill would stop surveillance of factories in China or cartels in Mexico. If an American does become a suspect in this trafficking, the government can and should seek a probable cause warrant, as is routinely done in domestic law enforcement cases. No sooner did we bat that one away than we heard about fresh terminological inexactitudes. Here are two of the latest bits of disinformation being circulated on Capitol Hill about the Protect Liberty Act. Intelligence Community Myth: Members of Congress are being told that under the Protect Liberty Act, the FBI would be forced to seek warrants from district court judges, who might or might not have security clearances, in order to perform U.S. person queries. Fact: The Protect Liberty Act allows the FBI to conduct U.S. person queries if it has either a warrant from a regular federal court or a probable cause order from the FISA Court, where judges have high-level security clearances. The FBI will determine which type of court order is appropriate in each case. Intelligence Community Myth: Members are being told that under the Protect Liberty Act, terrorists can insulate themselves from surveillance by including a U.S. person in a conversation or email thread. Fact: Under the Protect Liberty Act, the FBI can collect any and all communications of a foreign target, including their communications with U.S. persons. Nothing in the bill prevents an FBI agent from reviewing U.S. person information the agent encounters in the course of reviewing the foreign target’s communications. In other words, if an FBI agent is reading a foreign target’s emails and comes across an email to or from a U.S. person, the FBI agent does not need a warrant to read that email. The bill’s warrant requirement applies in one circumstance only: when an FBI agent runs a query designed to retrieve a U.S. person’s communications or other Fourth Amendment-protected information. That is as it should be under the U.S. Constitution. As we face the renewed debate over Section 702 – which must be reauthorized in the next few months – expect the parade of untruths to continue. As they do, PPSA will be here to call them out. National Rifle Association v. Vullo In this age of “corporate social responsibility,” can a government regulator mount a pressure campaign to persuade businesses to blacklist unpopular speakers and organizations? Would such pressure campaigns force banks, cloud storage companies, and other third parties that hold targeted organizations’ data to compromise their clients’ Fourth as well as their First Amendment rights?

These are just some of the questions PPSA is asking the U.S. Supreme Court to weigh in National Rifle Association v. Vullo. Here's the background on this case: Maria Vullo, then-superintendent of the New York Department of Financial Services, used her regulatory clout over banks and insurance companies in New York to strongarm them into denying financial services to the National Rifle Association. This campaign was waged under an earnest-sounding directive to consider the “reputational risk” of doing business with the NRA and firearms manufacturers. Vullo imposed consent orders on three insurers that they never again provide policies to the NRA. She issued guidance that encouraged financial services firms to “sever ties” with the NRA and to “continue evaluating and managing their risks, including reputational risks” that could arise from their dealings with the NRA or similar gun promotion organizations. “When a regulator known to slap multi-million fines on companies issues ‘guidance,’ it is not taken as a suggestion,” said Gene Schaerr, PPSA general counsel. “It’s sounds more like, ‘nice store you’ve got here, it’d be shame if anything happened to it.’” The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit reversed a lower court’s decision that found that Vullo used threats to force the companies she regulates to cut ties with the NRA. The Second Circuit reasoned that: “The general backlash against gun promotion groups and businesses … could (and likely does) directly affect the New York financial markets; as research shows, a business's response to social issues can directly affect its financial stability in this age of enhanced corporate social responsibility.” You don’t have to be an enthusiast of the National Rifle Association to see the problems with the Second Circuit’s reasoning. Aren’t executives of New York’s financial services firms better qualified to determine what does and doesn’t “directly affect financial stability” than a regulator in Albany? How aggressive will government become in using its almost unlimited access to buy or subpoena data of a target organization to get its way? We told the Court: “Even the stability of a single company is not enough; the government cannot override the Bill of Rights to slightly reduce the rate of corporate bankruptcies.” In our brief, PPSA informs the U.S. Supreme Court about the dangers of a nebulous, government-imposed “corporate social responsibility standard.” We write: “Using CSR – a controversial theory positing that taking popular or ‘socially responsible’ stances may increase corporate profits – to justify infringement of First Amendment rights poses a grave threat to all Constitutionally-protected individual rights.” PPSA is reminding the Court that the right to free speech and the right to be protected from government surveillance are intwined. “Once again, the House has passed the Protect Reporters from Exploitive State Spying (PRESS) Act with unanimous, bipartisan support. Forty-nine states have press shield laws protecting journalists and their sources from the prying eyes of prosecutors. The federal government does not. From Fox News to The New York Times, government has surveilled journalists in order to catch their sources. Journalists have been held in contempt and even jailed for bravely safeguarding the trust of their sources.

“The PRESS Act corrects this by granting a privilege to protect confidential news sources in federal legal proceedings, while offering reasonable exceptions for extreme situations. Such laws work well for the states and would safeguard Americans’ right to evaluate claims of secret wrongdoing for themselves. “Great credit goes to Rep. Kevin Kiley and Rep. Jamie Raskin for lining up bipartisan support for this reaffirmation of the First Amendment. As in 2022, the last time the House passed this act, the duty now shifts to the U.S. Senate to respond to this display of unanimous, bipartisan support. I am optimistic. At a time of gridlock, enacting this bill into law would be a positive message that would reflect well on every Senator.” CVS, Kroger, and Rite Aid Hand Over Americans’ Prescriptions Records to Police Upon Request1/17/2024

Three of the largest pharmaceutical chains – CVS Health, Kroger, and Rite Aid – routinely hand over the prescription and medical records of Americans to police and government agencies upon request, no warrant required.

“Americans' prescription records are among the most private information the government can obtain about a person,” Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR), and Reps. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) and Sara Jacobs (D-CA) wrote in a letter to HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra revealing the results of a congressional investigation into this practice. “They can reveal extremely personal and sensitive details about a person’s life, including prescriptions for birth control, depression or anxiety medications, or other private medical conditions.” The Washington Post reports that because the chains often share records across all locations, a pharmacy in one state can access a person’s medical history from states with more restrictive laws. Five pharmacies – Amazon, Cigna, Optum Rx, Walmart, and Walgreens Boots Alliance – require demands for pharmacy records by law enforcement to be reviewed by legal professionals. One of them, Amazon, informs consumers of the request unless hit with a gag order. All the major pharmacies will release customer records, however, if they are merely given a subpoena issued by a government agency rather than a warrant issued by a judge. This could be changed by corporate policy. Sen. Wyden and Reps. Jayapal and Jacobs urge pharmacies to insist on a warrant rather than comply with a request or a subpoena. Most Americans are familiar with the strict privacy provisions of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) from filling out forms in the doctor’s office. Most will surely be surprised how HIPAA, as strict as it is for physicians and hospitals, is wide open for warrantless inspection by the government. This privacy vulnerability is just one more example of the generous access government agencies have to almost all of our information. Intelligence and law enforcement agencies can know just about everything about us through purchases of our most sensitive and personal information reaped by our apps and sold to the government by data brokers. As privacy champions in Congress press HHS to revise its HIPAA regulations to protect Americans’ medical data from warrantless inspection, Congress should also close all the loopholes by passing the Protect Liberty and End Warrantless Surveillance Act. The Federal Reserve Board is publicly weighing whether or not to ask Congress to allow it to establish a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC), replacing paper dollars with government-issued electrons.

Given the growth of computing, a digital national currency may seem inevitable. But it would be a risky proposition from the standpoint of cybersecurity, national security, and unintended consequences for the economy. A CBDC would certainly pose a significant threat to Americans’ privacy. A factsheet on the Federal Reserve website says, “Any CBDC would need to strike an appropriate balance between safeguarding the privacy rights of consumers and affording the transparency necessary to deter criminal activity.” The Fed imagines that such a scheme would rely on privacy-sector intermediaries to create digital wallets and protect consumers’ privacy. Given the hunger that officialdom in Washington, D.C., has shown for pulling in all our financial information – including a serious proposal to record transactions from bank accounts, digital wallets, and apps – the Fed’s balancing of our privacy against surveillance of the currency is troubling. With digital money, government would have in its hands the ability to surveil all transactions, tracing every dollar from recipient to spender. Armed with such power, the government could debank any number of disfavored groups or individuals. If this sounds implausible, consider that debanking was exactly the strategy the Canadian government used against the trucker protestors two years ago. Enter H.R. 1122 – the CBDC Anti-Surveillance State Act – which sets down requirements for a digital currency. This bill would prohibit the Federal Reserve from using CBDC to implement monetary policy. It would require the Fed to report the results of a study or pilot program to Congress on a quarterly basis and consult with the brain trust of the Fed’s regional banks. Though this bill prevents the Fed from issuing CBDC accounts to individuals directly, there is a potential loophole in this bill – the Fed might still maintain CBDC accounts for corporations (the “intermediaries” the Fed refers to). The sponsors may want to close any loopholes there. That’s a quibble, however. This bill, sponsored by Rep. Tom Emmer (R-MO), Majority Whip of the House, with almost 80 co-sponsors, is a needed warning to the Fed and to surveillance hawks that a financial surveillance state is unacceptable. The American Civil Liberties Union, its Northern California chapter, and the Brennan Center, are calling on the Federal Trade Commission to investigate whether Meta and X have broken commitments they made to protect customers from data brokers and government surveillance.

This concern goes back to 2016 when it came to light that Facebook and Twitter helped police target Black Lives Matter activists. As a result of protests by the ACLU of Northern California and other advocacy groups, both companies promised to strengthen their anti-surveillance policies and cut off access to social media surveillance companies. Their privacy promises even became points of pride in these companies’ advertising. Now ACLU and Brennan say they have uncovered commercial documents from data brokers that seem to contradict these promises. They point to a host of data companies that publicly claim they have access to data from Meta and/or X, selling customers’ information to police and other government agencies. ACLU writes: “These materials suggest that law enforcement agencies are getting deep access to social media companies’ stores of data about people as they go about their daily lives.” While this case emerged from left-leaning organizations and concerns, organizations and people on the right have just as much reason for concern. The posts we make, what we say, who our friends are, can be very sensitive and personal information. “Something’s not right,” ACLU writes. “If these companies can really do all that they advertise, the FTC needs to figure out how.” At this point, we simply don’t know with certainty which, if any, social media platforms are permitting data brokers to obtain personal information from their platforms – information that can then be sold to the government. Regardless of the answer to that question, PPSA suggests that a thorough way to short-circuit any extraction of Americans’ most sensitive and personal information from data sales (at least at the federal level) would be to pass the strongly bipartisan Protect Liberty and End Warrantless Surveillance Act. This measure would force federal government agencies to obtain a warrant – as they should anyway under the Fourth Amendment – to access the data of an American citizen. A letter of protest sent by the lawyers of Rabbi Levi Illulian in August alleged that city officials of Beverly Hills, California, had investigated their client’s home for hosting religious gatherings for his family, neighbors, and friends. Worse, the city used increasingly invasive means, including surveilling people visiting the rabbi’s home, and flying a surveillance drone over his property.

A “notice of violation” from the city specifically threatened Illulian with civil and criminal proceedings for “religious activity” at his home. The notice further prohibited all religious activity at Illulian’s home with non-residents. With support from First Liberty Institute, the rabbi’s lawyers sent another letter detailing an egregious use of city resources to launch a “full-scale investigation against Rabbi Illulian” in which “city personnel engaged in multiple stakeouts of the home over many hours, effectively maintaining a governmental presence outside Rabbi Illulian’s home.” The rabbi’s Orthodox Jewish friends and family who visited his home had also received parking citations. The rabbi began to receive visits from the police for noise disturbances, such as on Halloween when other houses on the street were sources of noise as well. Police even threatened to charge Rabbi Illulian with a misdemeanor, confiscate his music equipment, and cite a visiting musician for violating the city’s noise ordinance, despite the obvious double-standard. First Liberty was active in publicizing the city’s actions. In the face of bad publicity about this aggressive enforcement, the city withdrew its violation notice late last year. That the city of Beverly Hills would blatantly monitor and harass a household over Shabbat prayers and religious holidays, particularly at a time of rising antisemitism, is made all the worse by sophisticated forms of surveillance aimed at the free exercise of religion. So city officials managed to abuse the Fourth Amendment to impinge on the First Amendment. This case is reminiscent of the surveillance of a church, Calvary Chapel San Jose, by Santa Clara, California, county officials, over its Covid-19 policies. Is there something about religious observances that attracts the ire of some local officials? Whatever their reasons, this story is the latest example of the need for local officials who are better acquainted with the Constitution. Agencies Must Release Policy Documents About Purchase of the Personal Data of 145 Members of Congress Late last week, Judge Rudolph Contreras ordered the NSA, the CIA, the FBI, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence to respond to a PPSA Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. The government now has two weeks to schedule the production of “policy documents” regarding the intelligence community’s acquisition and use of commercially available information regarding 145 current and former Members of Congress.

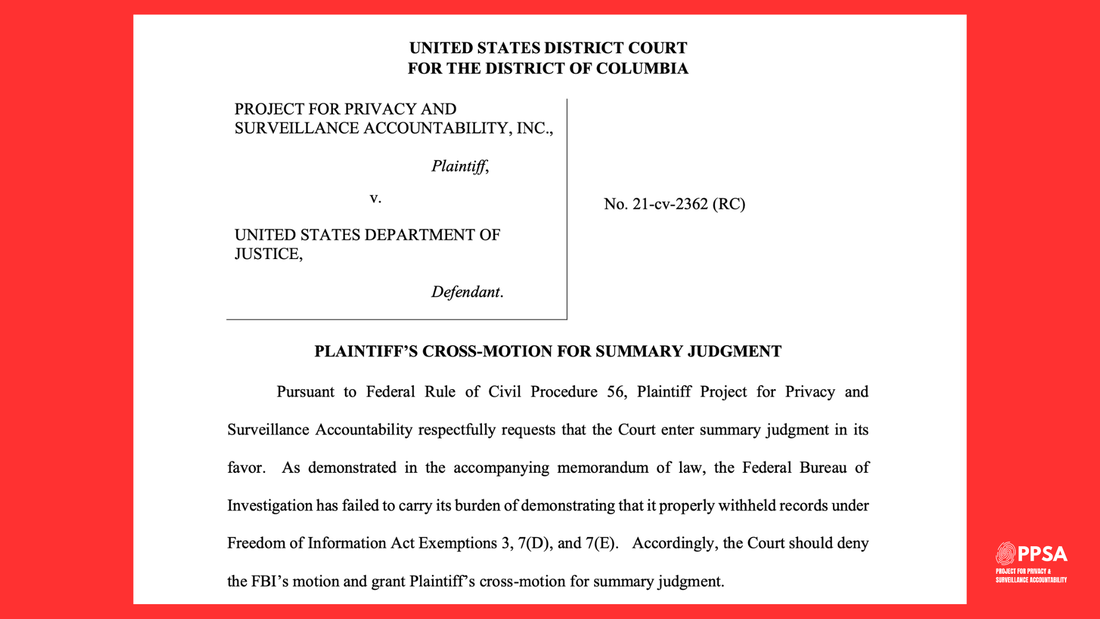

This is the second time Judge Contreras has had to tell federal agencies to respond to a FOIA request PPSA submitted. In late 2022, Judge Contreras rejected in part the FBI’s insistence that the Glomar doctrine allowed it to ignore FOIA’s requirement to search for responsive records. Despite that clear holding, the FBI – joined this time by several other agencies – again refused to search for records in response to PPSA’s FOIA request. And Judge Contreras had to remind the agencies again that FOIA’s search obligations cannot be ducked so easily. Instead, Judge Contreras found that PPSA “logically and plausibly” requested the policy documents about the acquisition of commercially available information. And Judge Contreras concluded that a blanket Glomar response, in which the government neither confirms nor denies the existence of the requested documents, is appropriate only when a Glomar response is justified for all categories of responsive records. The judge then described a hypothetical letter from a Member of Congress to the NSA that clarifies the distinction between operational and policy documents. He considered that such a letter might ask if the NSA “had purchased commercially available information on any of the listed Senators or Congresspeople” without revealing whether the NSA (or any other of the defendant agencies) “had a particular interest in surveilling the individual.” Judge Contreras decided that “it is difficult to see how a document such as this would reveal sensitive information about Defendants’ intelligence activities, sources, or methods.” It is on this reasoning that the judge ordered these agencies to produce these policies documents. We eagerly awaits the delivery of these documents in both cases. Stay tuned. PPSA today announced that it is asking the District Court for the District of Columbia to force the FBI to produce two records about communications between government agencies and Members of Congress concerning their possible “unmasking” in secretly intercepted foreign conversations under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA).

PPSA’s request to the court involves the practice of naming Americans – in this case, Members of the House and Senate – who are caught up in foreign surveillance summaries. In 2017, Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) said he had reason to believe his identify had been unmasked and that he had written to the FBI about it. Similar statements have been made by other Members of Congress of both parties. The matter seemed to have been settled in October 2022 when Judge Rudolph Contreras of the U.S. District Court of the District of Columbia declared that “communications between the FBI and Congress are a degree removed from FISA-derived documents and which discuss congressional unmasking as a matter of legislative interest, policy, or oversight … the FBI must conduct a search for any ‘policy documents’ in its possession.” The FBI had first refused to release these documents under a broad and untenable interpretation of the Glomar doctrine, under which the government asserts it can neither confirm nor deny the existence of such records for national security reasons. After Judge Contreras swept that excuse away, the FBI in October 2023 asserted that three FOIA exemptions allow it to withhold requested documents. The FBI has gone from obfuscation to outright defiance of the plain text of the law. It still claims that releasing correspondence with Congress would, somehow, endanger intelligence sources and methods. It is time for the court to step in and issue a legal order the FBI cannot openly defy. Thus PPSA’s cross motion for summary judgment knocks down the FBI’s rationale and asks Judge Contreras to order the FBI to produce all FBI records reflecting communications between the government and Members of Congress on their “unmasking.” Earlier, the FBI had searched under a court order to find two relevant policy documents. These unreleased records include a four-page email between FBI employees and an FBI Intelligence Program Policy Guide. Significant portions of both documents are being withheld by the FBI because, the Bureau now asserts, of the three exemptions. It claims the disclosure can be withheld because it could implicate sources and methods, the records were created for law enforcement purposes, and because of confidentiality. None of these excuses meet the laugh test for correspondence with Members of Congress. PPSA is optimistic the court will end the FBI’s two years of foot-dragging and order it to produce. PPSA has long warned that most drivers don’t realize that a modern car is a digital recording device. It tracks our travels, call logs, private text messages, even the impression our weight makes on our seat. Our car knows if we’re driving alone or with someone else. In all, a contemporary car accumulates vast amounts of data every day, much of it about us, where we’re going, and sometimes with whom.

Kashmir Hill in a recent New York Times piece described how a car can be turned into a digital weapon by a stalker or abusive partner. In one instance, a woman in divorce proceedings realized that her husband was tracking her through the location-based service in her Mercedes. When the woman visited a male friend, her husband sent the man a message with a thumbs-up emoji. Another woman, also estranged from her spouse, found that he was remotely causing her parked Tesla to turn on with heat blasting on hot days, and cold air streaming on cold days. Hill memorably wrote: “A car, to its driver, can feel like a sanctuary. A place to sing favorite songs off key, to cry, to vent or to drive somewhere no one knows you’re going.” That sanctuary, of course, is an illusion. Hill’s piece pointed not just to stalkers, but to the sharing of drivers’ consumer data with insurance companies and car companies. PPSA has long warned of yet another sinister use of car-generated data. About a dozen federal law enforcement and intelligence agencies make free use of the data broker loophole to purchase consumer data scraped from our apps. There is no law or rule that forbids them from purchasing car-generated data as well. This vulnerability will only get worse if a Congressional mandate for a built-in drunk driver detection system leads to cameras and microphones allowing AI to passively monitor drivers’ movements and speech for signs of impairment. Sens. Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Cynthia Lummis (R-WY), and Rep. Ro Khanna (D-CA), have addressed what government can do with car data under proposed legislation, “Closing the Warrantless Digital Car Search Loophole Act.” This bill would require law enforcement to obtain a warrant based on probable cause before searching data from any vehicle that does not require a commercial license. Another similar solution for all purchased commercial data is contained in the Protect Liberty and End Warrantless Surveillance Act, which passed the House Judiciary Committee with overwhelming bipartisan support. The most maddening thing about all this car-generated data is that much of it is off-limits to the drivers themselves, especially if someone else (like an ex-spouse) owns the car’s title. Cars are driving the expectation of privacy off the road. It is time for Congress to act. Man proposes, God disposes, but Congress often just kicks the can down the road.

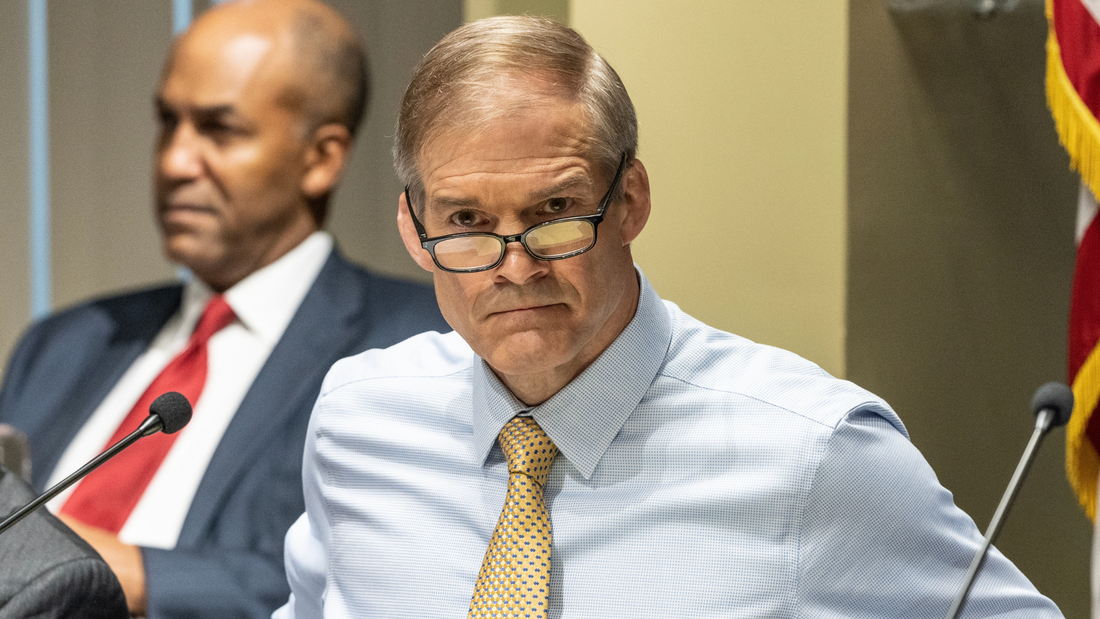

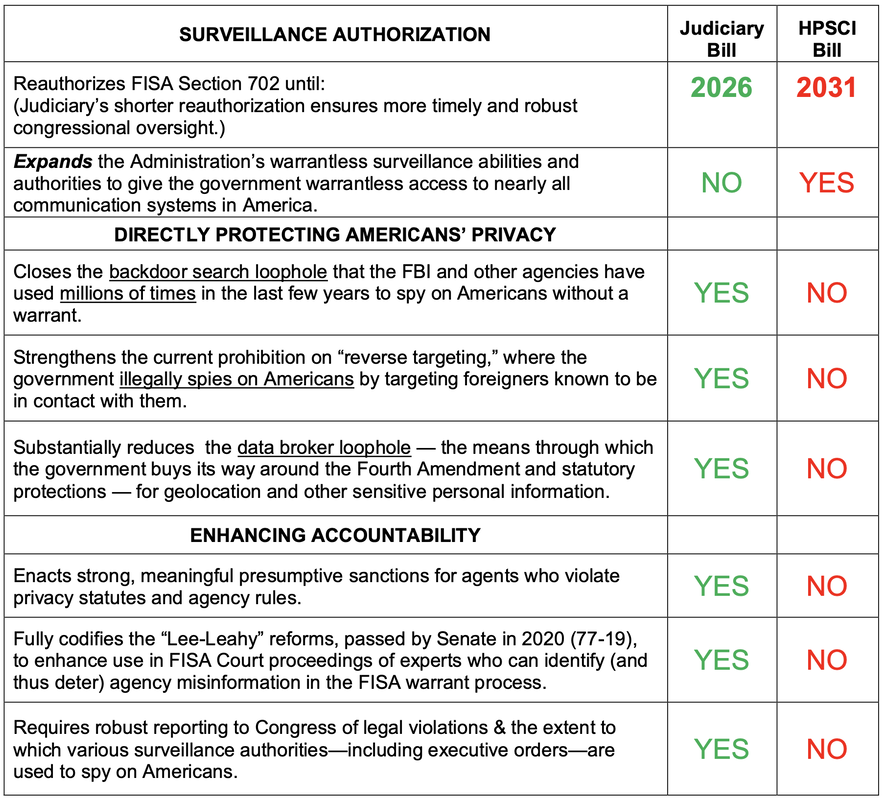

Throughout 2023, PPSA and our civil liberties allies made the case that Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act – enacted by Congress to give federal intelligence agencies the authority to surveil foreign threats abroad – has become a convenient excuse for warrantless domestic surveillance of millions of Americans in recent years. With Section 702 set to expire, the debate over reauthorizing this authority necessarily involves reforms and fixes to a law that functions in a radically different way than its Congressional authors imagined. In December, a strong bipartisan majority in the House Judiciary Committee passed a well-crafted bill to reauthorize FISA Section 702 – the Protect Liberty and End Warrantless Surveillance Act. This bill mandates a robust warrant requirement for U.S. person searches. It curtails the common government surveillance technique of “reverse targeting,” which uses Section 702 to work backwards to target Americans without a warrant. It also closes the loophole that allows government agencies to buy access to Americans’ most sensitive and personal information scraped from our apps and sold by data brokers. And the Protect Liberty Act requires the inclusion of lawyers with high-level clearances who are experts in civil liberties to ensure the secret FISA Court hears from them as well as from government attorneys. The FISA Reform and Reauthorization Act from the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence would not stop the widespread practice of backdoor searches of Americans’ information. And it does not address the outrageous practice of federal agencies buying up Americans’ most sensitive and private information from data brokers. In the crush of business, the deadline for reauthorizing Section 702 was delayed until early spring. Now the contest between the two approaches to Section 702 reauthorization begins in earnest. With a recent FreedomWorks/Demand Progress poll showing that 78 percent of Americans support strengthening privacy protections along the lines of those in the Protect Liberty Act, reformers go into the year with a strong tailwind. While we should never underestimate the guile of the intelligence community, reformers look to the debate ahead with hopefulness and eagerness to win this debate to protect the privacy of all Americans. In July, we wrote about revelations that the U.S. Department of Justice subpoenaed Google for the private data of House Intel staffers looking into the origins of the FBI’s Russiagate investigation. Then, in October, we wrote about a FOIA request from Empower Oversight seeking documents shedding light on the extent to which the executive branch is spying on Members of Congress. Now, following the launch of an official inquiry, Rep. Jim Jordan has issued a subpoena to Attorney General Merrick Garland for further information on the DOJ’s efforts to surveil Congress and congressional staff.

On Halloween, Jordan launched his inquiry into the DOJ’s apparent attempts to spy on Congress, sending letters to the CEOs of Alphabet, Apple, AT&T, T-Mobile, and Verizon requesting, for example, “[a]ll documents and communications between or among Apple employees and Justice Department employees referring or relating to subpoenas or requests issued by the Department of Justice to Apple for personal or official records or communications of Members of Congress or congressional staff….” Jordan also sent a letter to Garland, asserting that “[t]he Justice Department’s efforts to obtain the private communications of congressional staffers, including staffers conducting oversight of the Department, is wholly unacceptable and offends fundamental separation of powers principles as well as Congress’s constitutional authority to conduct oversight of the Justice Department.” Nearly two months later, according to Jordan, the DOJ’s response has been insufficient. In a letter to Garland dated December 19, 2023, Jordan says that the “Committee must resort to compulsory process” due to “the Department’s inadequate response to date.” That response, to be fair, did include a letter to Jordan dated December 4 conveying that the legal process used related to an investigation “into the unauthorized disclosure of classified information in a national media publication. Jordan, citing news reports, contends that the investigation actually “centered on FISA warrants obtained by the Justice Department on former Trump campaign associate Carter Page” (which the Justice Department Inspector General faulted for “significant inaccuracies and omissions”). Whatever the underlying motivation, Jordan is right to find DOJ’s explanation to date unsatisfying. Spying on Congress not only brings with it tremendous separation of powers concerns but raises a broader question about FISA and other processes that would reveal Americans’ personal information without sufficient predication. We need answers. Who authorized these DOJ subpoenas? And how can we make sure this kind of thing doesn’t happen again? PPSA looks forward to further developments in this story. Less consumer tracking leads to less fraud. That’s the key takeaway from a new study conducted by the National Bureau of Economic Research in its working paper, “Consumer Surveillance and Financial Fraud.”

Using data obtained from the Federal Trade Commission and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, as well as the geospatial data firm Safegraph, the authors looked at the correlation between Apple’s App Tracking Transparency framework and consumer fraud reports. Apple’s ATT policy requires user authorization before other apps can track and share customer data. In April 2021, Apple made this the default setting on all iPhones, ensuring that users would no longer be automatically tracked when they visit websites or use apps. This in turn dealt a hefty financial blow to companies like Snap, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, which collectively lost about $10 billion after implementation. The authors of the paper obtained fraud complaint figures from the FTC and the CFPB, then employed machine learning and targeted keyword searches to isolate complaints stemming from data privacy issues. They then cross-referenced those complaints with data acquired by Safegraph showing the number of iPhone users in a given ZIP code. According to the paper, a 10% increase in Apple users within a given ZIP code leads to a 3.21% reduction in financial fraud complaints. As the Electronic Frontier Foundation points out in a recent article about the study: “While the scope of the data is small, this is the first significant research we’ve seen that connects increased privacy with decreased fraud. This should matter to all of us. It reinforces that when companies take steps to protect our privacy, they also help protect us from financial fraud.” Obviously, more companies should follow Apple’s lead in implementing ATT-like policies. More than that, however, we need better and more robust laws on the books protecting consumer privacy. California has passed a number of related bills in recent years, most recently creating a one-stop opt-out mechanism for data collection. Colorado did the same. As other states and nations (and even CIA agents) wake up to the dangers of data tracking, this new study can serve as compelling, direct evidence showing why more restrictive settings – and consumer privacy – should always be the default. With Congress extending the reauthorization of FISA Section 702 until April, the debate over surveillance can be expected to fire up again when Members return in January. As Members relax and reorient over the holidays, we urge them to take a moment to listen to what the American people are saying.

The conservative FreedomWorks and the progressive Demand Progress, both highly respected advocacy organizations with deep grassroots, came together to conduct a national poll on the public’s approval of specific measures. Some of these measures are in the FISA Reform and Reauthorization Act passed by the House Intelligence Committee, and some in the Protect Liberty and End Warrantless Surveillance Act, passed 35-2 by the House Judiciary Committee. Across the board, Americans overwhelmingly support the provisions in the Protect Liberty Act.

House Judiciary Chairman Jim Jordan, writing in The Wall Street Journal, declared that, “in the wake of serious FISA abuses, our fidelity must be to the Constitution, not the surveillance state.” The FreedomWorks/Demand Progress poll shows that the American people agree. Just before Congress punted – delaying debate over reform proposals to Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Act – Sen. Mike Lee (R-UT) took to the Senate floor to describe how much is at stake for Americans.

Sen. Lee did not mince his words, saying Section 702 “is widely, infamously, severely abused” as “hundreds of thousands of American citizens have become victims of …warrantless backdoor searches.” The senator’s frustration boiled over when he spoke of questioning FBI directors in hearings, being told by them “don’t worry” because the FBI has strong procedures in place to prevent abuses. “We’re professionals,” they said. These promises from FBI directors, Sen. Lee said, are “like a curse,” an indication that the violation of Americans’ civil rights “gets worse every single time they say it.” The good news is that, although champions of reform fell short in Thursday’s vote, 35 senators in both parties were so bothered by the extension of Section 702 in its current form that they voted against its inclusion in the National Defense Authorization Act. What appears to be a temporary extension of Section 702 leaves the door open, we hope, for a fuller debate and vote on reform provisions early next year. When that happens, Sen. Lee will surely be in the lead. Here is the bipartisan honor roll of senators who voted in favor of surveillance reform. Tammy Baldwin (D-WI), Marsha Blackburn (R-TN), Cory Booker (D-NJ), Mike Braun (R-IN), Sherrod Brown (D-OH), Maria Cantwell (D-WA), Kevin Cramer (R-ND), Steve Daines (R-MT), Dick Durbin (D-IL), Chuck Grassley (R-IA), Bill Hagerty (R-TN), Josh Hawley (R-MO), Martin Heinrich (D-NM), Mazie Hirono (D-HI), John Hoeven (R-ND), Ron Johnson (R-WI), Mike Lee (R-UT), Ben Ray Lujan (D-NM), Cynthia Lummis (R-WY), Ed Markey (D-MA), Roger Marshall (R-KS), Robert Menendez (D-NJ), Jeff Merkley (D-OR), Rand Paul (R-KY), Bernie Sanders (I-VT), Eric Schmitt (R-MO), Rick Scott (R-FL), John Tester (D-MT),Tommy Tuberville (R-AL), Chris Van Hollen (D-MD), J.D. Vance (R-OH), Raphael Warnock (D-GA), Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), Peter Welch (D-VT), and Ron Wyden (D-OR). PPSA has often covered abuses of the geolocation tracking common to cellphones – from local governments in California spying on church-goers, to “warrant factories” in Virginia in which police obtain hundreds of warrants for thousands of surveillance days, often for minor infractions.

Geolocation tracking can be among the most pernicious compromises of personal privacy. In Carpenter v. United States (2018), the U.S. Supreme Court held that warrants are needed to inspect cellphone records extracted from cell-site towers, recognizing just how personal a target’s movements can be. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote: “Unlike the nosy neighbor who keeps an eye on comings and goings, they [new technologies] are ever alert, and memory is nearly infallible.” The narrowness of Carpenter has not, however, prevented the FBI and other federal agencies from tracking people’s movements without a warrant by merely buying their data from third-party data brokers. The FBI may soon, however, have much less to buy. Orin Kerr, writing in the Volokh Conspiracy in Reason, informs us that “Google will no longer keep location history even for the users who opted to have it turned on. Instead, the location history will only be kept on the user’s phones.” Kerr adds: “If Google doesn’t keep the records, Google will have no records to turn over.” A corporate decision in Silicon Valley has thus removed a major pillar of government surveillance. It says something about the current state of this country when a Big Tech giant is more responsive to consumers than government is to its citizens. But don’t be surprised if the feds start to pressure Google to reverse its decision. The Project for Privacy and Surveillance Accountability (PPSA) will be scoring this week’s votes on each of the two competing bills to reauthorize Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. For our followers, PPSA will positively score Members who vote in favor of the Protect Liberty and End Warrantless Surveillance Act, which passed the House Judiciary Committee this week in an overwhelming bipartisan 35-2 vote. We will negatively score Members who vote in favor of the FISA Reform and Reauthorization Act from the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence. PPSA supports the Protect Liberty bill because it places critical guardrails and limits on warrantless FBI and other government surveillance of Americans, while reauthorizing Section 702 to protect national security. PPSA opposes the HPSCI bill because it rubberstamps the FBI’s and other agencies’ warrantless surveillance of Americans for years to come, while actually expanding the ability of the government to spy on Americans. The table below highlights the key differences between the two bills. Judiciary’s Protect Liberty and End Warrantless Surveillance Act

|

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed