|

PPSA has fired off a succession of Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to leading federal law enforcement and intelligence agencies. These FOIAs seek critical details about the government’s purchasing of Americans’ most sensitive and personal data scraped from apps and sold by data brokers.

PPSA’s FOIA requests were sent to the Department of Justice and the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security, the CIA, the Defense Intelligence Agency, the National Security Agency, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, asking these agencies to reveal the broad outlines of how they collect highly private information of Americans. These digital traces purchased by the government reveal Americans’ familial, romantic, professional, religious, and political associations. This practice is often called the “data broker loophole” because it allows the government to bypass the usual judicial oversight and Fourth Amendment warrant requirement for obtaining personal information. “Every American should be deeply concerned about the extent to which U.S. law enforcement and intelligence agencies are collecting the details of Americans’ personal lives,” said Gene Schaerr, PPSA general counsel. “This collection happens without individuals’ knowledge, without probable cause, and without significant judicial oversight. The information collected is often detailed, extensive, and easily compiled, posing an immense threat to the personal privacy of every citizen.” To shed light on these practices, PPSA is requesting these agencies produce records concerning:

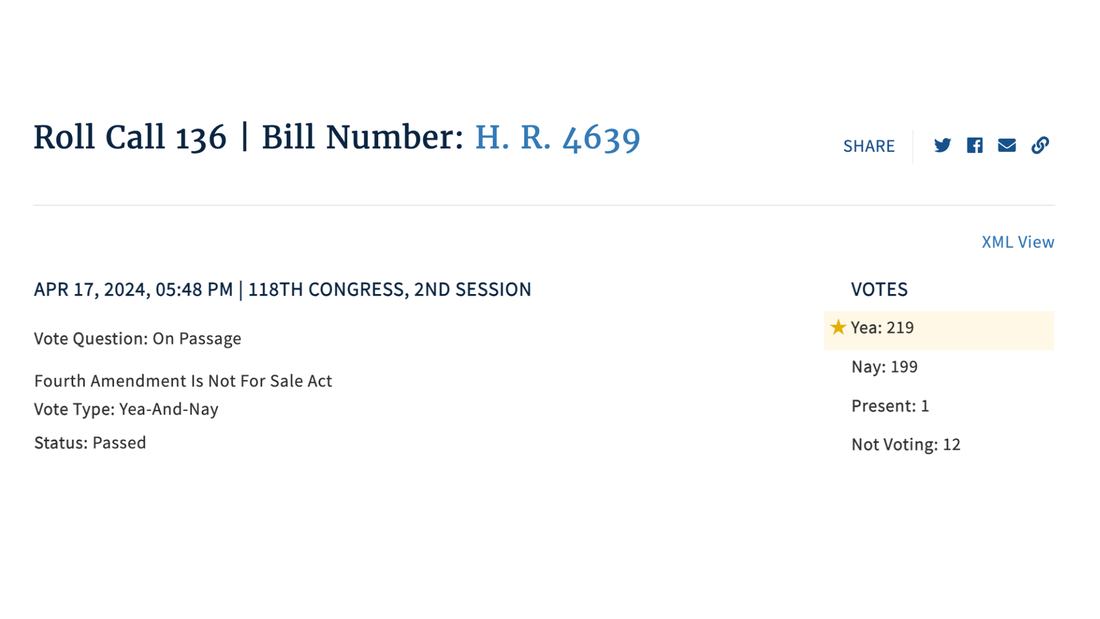

Shortly after the House passed the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, which would require the government to obtain probable cause warrants before collecting Americans’ personal data, Avril Haines, Director of National Intelligence, ordered all 18 intelligence agencies to devise safeguards “tailored to the sensitivity of the information.” She also directed them to produce an annual report on how each agency uses such data. PPSA believes that revealing, in broad categories, the size, scope, sources, and types of data collected by agencies, would be a good first step in Director Haines’ effort to provide more transparency on data purchases. “Curtilage” is a legal word that means the enclosed area around a home in which the occupant has an expectation of privacy. Within the zone of curtilage, the Fourth Amendment implications usually force law enforcement officers to obtain a warrant before they can enter. Where curtilage begins and ends has long been a matter of fine, Jesuitic distinctions, hotly contested in courts across the country.

Sometimes the boundaries are obvious. In a landmark case, the U.S. Supreme Court in 2021 held in Lange v. California that a police officer who followed a driver into his garage entered his curtilage. The officer had no right to do so without a warrant. PPSA was pleased to see the Court adopt logic similar to our amicus brief in Lange. So much for garages. Now what about doorknobs? Terrell McNeal Jr. of Mankato, Minnesota, was arrested after police obtained a probable cause warrant to enter his apartment and found controlled substances, cash, and guns. The evidence behind the warrant was derived from his doorknob. A police officer had earlier obtained a code from the apartment’s landlord to enter the structure’s interior communal space. He had proceeded to swab the doorknob of McNeal’s front door. It tested positive for two controlled substances. That was the basis of the warrant. The doorknob was tainted, to be sure. But that left a nagging legal question: Was the search warrant itself tainted by a violation of McNeal’s curtilage? A district court did not think so. It bought the prosecution’s argument that the door handle and lock were outside of McNeal’s home. A county prosecutor made this point on appeal: “If the court looks at the door itself, it prevents people from looking into the home. That doesn’t make the outside of the door curtilage.” Actually, it does, ruled the Minnesota Court of Appeals. On June 10, the appellate court found that officers have “no implied license to remove material from the door handle and lock for laboratory testing.” The court did distinguish this case from one in which a search warrant was obtained after a drug-sniffing dog found the aromatic traces of narcotics in the air in front of an apartment. But the officers in the McNeil case, the court ruled, “went a step further and collected a sample from a door handle and lock that were physically attached to and indivisible from appellant’s home.” The Minnesota Court of Appeals made the correct decision, voiding the conviction. As for McNeal, the authorities kept him in prison since his arrest more than two years ago, until the appellate court ruled in his favor. But at least the court recognized that swabbing any part of a home without a warrant is a violation of the Fourth Amendment. As the adoption of Automated License Plate Readers (ALPRs) creates ubiquitous surveillance of roads and highways, the uses and abuses of these systems – which capture and store license plate data – received fresh scrutiny by a Virginia court willing to question Supreme Court precedent.

In Norfolk, 172 such cameras were installed in 2023, generating data on just about every citizen’s movements available to Norfolk police and shared with law enforcement in neighboring jurisdictions. Enter Jayvon Antonio Bell, facing charges of robbery with a firearm. In addition to alleged incriminating statements, the key evidence against Bell includes photographs of his vehicle captured by Norfolk’s Flock ALPR system. Bell’s lawyers argued that the use of ALPR technology without a warrant violated Bell’s Fourth and Fourteenth Amendment rights, as well as several provisions of the Virginia Constitution. The Norfolk Circuit Court, in a landmark decision, granted Bell's motion to suppress the evidence obtained from the license plate reader. This ruling, rooted in constitutional protections, weighs in on the side of privacy in the national debate over data from roadway surveillance. The court was persuaded that constant surveillance and data retention by ALPRs creates, in the words of Bell’s defense attorneys, a “dragnet over the entire city.” This motion to dismiss evidence has the potential to reframe Fourth Amendment jurisprudence. The Norfolk court considered the implications of the Supreme Court opinion Katz v. United States (1967), which established that what a person knowingly exposes to the public is not protected by the Fourth Amendment. In its decision, the court boldly noted that technological advancements since Katz have expanded law enforcement's capabilities, making it necessary to re-evaluate consequences for Fourth Amendment protections. The court also referenced a Massachusetts case in which limited ALPR use was deemed not to violate the Fourth Amendment. The Norfolk Circuit Court’s approach was again pioneering. The court found that the extensive network of the 172 ALPR cameras in Norfolk, which far exceeded the limited surveillance in the Massachusetts case, posed unavoidable Fourth Amendment concerns. The Norfolk court also expressed concern about the lack of training requirements for officers accessing the system, and the ease with which neighboring jurisdictions could share data. Additionally, the court highlighted vulnerabilities in ALPR technology, citing research showing that these systems are susceptible to error and hacking. This is a bold decision by this state court, one that underscores the need for careful oversight and regulation of ALPR systems. As surveillance technology continues to evolve, this court’s decision to suppress evidence from a license plate reader is a sign that at least some judges are ready to draw a line around constitutional protections in the face of technological encroachment. In the early 1920s revenue agents staked out a South Carolina home the agents suspected was being used as a distribution center for moonshine whiskey. The revenue agents were in luck. They saw a visitor arrive to receive a bottle from someone inside the house. The agents moved in. The son of the home’s owner, a man named Hester, realized that he was about to be arrested and sprinted with the bottle to a nearby car, picked up a gallon jug, and ran into an open field.

One of the agents fired a shot into the air, prompting Hester to toss the jug, which shattered. Hester then threw the bottle in the open field. Officers found a large fragment of the broken jug and the discarded bottle both contained moonshine whiskey. This was solid proof that moonshine was being sold. But was it admissible as evidence? After all, the revenue agents did not have a warrant. This case eventually wound its way to the Supreme Court. In 1924, a unanimous Court, presided over by Chief Justice (and former U.S. President) William Howard Taft, held that the Fourth Amendment did not apply to this evidence. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, writing the Court’s opinion, declared that “the special protection accorded by the Fourth Amendment to the people in their ‘persons, houses, papers and effects,’ is not extended to the open field.” This principle was later extended to exclude any garbage that a person throws away from Fourth Amendment protections. As strange as it may seem, this case about broken jugs and moonshine from the 1920s, Hester v. United States, provides the principle by which law enforcement officers freely help themselves to the information inside a discarded or lost cellphone – text messages, emails, bank records, phone calls, and images. We reported a case in 2022 in which a Virginia man was convicted of crimes based on police inspection of a cellphone he had left behind in a restaurant. That man’s attorney, Brandon Boxler, told the Daily Press of Newport News that “cellphones are different. They have massive storage capabilities. A search of a cellphone involves a much deeper invasion of privacy. The depth and breadth of personal and private information they contain was unimaginable in 1924.” In Riley v. California, the Supreme Court in 2018 upheld that a warrant was required to inspect the contents of a suspect’s cellphone. But the Hester rule still applies to discarded and lost phones. They are still subject to what Justice Holmes called the rules of the open field. The American Civil Liberties Union, ACLU Oregon, the Electronic Privacy Information Center, and other civil liberties organizations are challenging this doctrine before the Ninth Circuit in Hunt v. United States. They told the court that it should not use the same reasoning that has historically applied to garbage left out for collection and items discarded in a hotel wastepaper basket. “Our cell phones provide access to information comparable in quantity and breadth to what police might glean from a thorough search of a house,” ACLU said in a posted statement. “Unlike a house, though, a cell phone is relatively easy to lose. You carry it with you almost all the time. It can fall between seat cushions or slip out of a loose pocket. You might leave it at the check-out desk after making a purchase or forget it on the bus as you hasten to make your stop … It would be absurd to suggest that a person intends to open up their house for unrestrained searches by police whenever they drop their house key.” Yet that is the government position on lost and discarded cellphones. PPSA applauds and supports the ACLU and its partners for taking a strong stand on cellphone privacy. The logic of extending special protections to cellphones, which the Supreme Court has held contain the “privacies of life,” is obvious. It is the government’s position that tastes like something cooked up in a still. State of Alaska v. McKelveyWe recently reported that the Michigan Supreme Court punted on the Fourth Amendment implications in a case involving local government’s warrantless surveillance of a couple’s property with drone cameras. This was a disappointing outcome, one in which we had filed an amicus brief on behalf of the couple.

But other states are taking a harder look at privacy and aerial surveillance. In another recent case, the Alaska Supreme Court in State v. McKelvey upheld an appeals court ruling that the police needed to obtain a warrant before using an aircraft with officers armed with telephoto lenses to see if a man was cultivating marijuana in his backyard at his home near Fairbanks. In a well-reasoned opinion, Alaska’s top court found that this practice was “corrosive to Alaskans’ sense of security.” The state government had argued that the observations did not violate any reasonable expectation of privacy because they were made with commercially available, commonly used equipment. “This point is not persuasive,” the Alaska justices responded. “The commercial availability of a piece of technology is not an appropriate measure of whether the technology’s use by the government to surveil violates a reasonable expectation of privacy.” The court’s reasoning is profound and of national significance: “If it is not a search when the police make observations using technology that is commercially available, then the constitutional protection against unreasonable searches will shrink as technology advances … As the Seventh Circuit recently observed, that approach creates a ‘precarious circularity.’ Adoption of new technologies means ‘society’s expectations of privacy will change as citizens increasingly rely on and expect these new technologies.’” That is as succinct a description of the current state of privacy as any we’ve heard. The court found that “few of us anticipated, when we began shopping for things online, that we would receive advertisements for car seats and burp cloths before telling anyone there was a baby on the way.” We would add that virtually no one in the early era of social media anticipated that federal agencies would use it to purchase our most intimate and sensitive information from data brokers without warrants. The Alaska Supreme Court sees the danger of technology expansion with drones, which it held is corrosive to Alaskans’ sense of privacy. As we warned, drones are becoming ever cheaper, sold with combined sensor packages that can be not only deeply intrusive across a property, but actually able to penetrate into the interior of a home. The Alaska opinion is an eloquent warning that when it comes to the loss of privacy, we’ve become the proverbial frog, allowing ourselves to become comfortable with being boiled by degrees. This opinion deserves to be nationally recognized as a bold declaration against the trend of ever-more expanding technology and ever-more shrinking zones of privacy. Now that the House has passed the Fourth Amendment Is Not for Sale Act, senators would do well to review new concessions from the intelligence community on how it treats Americans’ purchased data. This is progress, but it points to how much more needs to be done to protect privacy.

Avril Haines, Director of National Intelligence (DNI), released a “Policy Framework for Commercially Available Information,” or CAI. In plain English, CAI is all the digital data scraped from our apps and sold to federal agencies, ranging from the FBI to the IRS, Department of Homeland Security, and Department of Defense. From purchased digital data, federal agents can instantly access almost every detail of our personal lives, from our relationships to our location histories, to data about our health, financial stability, religious practices, and politics. Federal purchases of Americans’ data don’t merely violate Americans’ privacy, they kick down any semblance of it. There are signs that the intelligence community itself is coming to realize just how extreme its practices are. Last summer, Director Haines released an unusually frank report from an internal panel about the dangers of CAI. We wrote at the time: “Unlike most government documents, this report is remarkably self-aware and willing to explore the dangers” of data purchases. The panel admitted that this data can be used to “facilitate blackmail, stalking, harassment, and public shaming.” Director Haines’ new policy orders all 18 intelligence agencies to devise safeguards “tailored to the sensitivity of the information” and produce an annual report on how each agency uses such data. The policy also requires agencies:

Details for how each of the intelligence agencies will fulfill these aspirations – and actually handle “sensitive CAI” – is left up to them. Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR) acknowledged that this new policy marks “an important step forward in starting to bring the intelligence community under a set of principles and polices, and in documenting all the various programs so that they can be overseen.” Journalist and author Byron Tau told Reason that the new policy is a notable change in the government’s stance. Earlier, “government lawyers were saying basically it’s anonymized, so no privacy problem here.” Critics were quick to point out that any of this data could be deanonymized with a few keystrokes. Now, Tau says, the new policy is “sort of a recognition that this data is actually sensitive, which is a bit of change.” Tau has it right – this is a bit of a change, but one with potentially big consequences. One of those consequences is that the public and Congress will have metrics that are at least suggestive of what data the intelligence community is purchasing and how it uses it. In the meantime, Sen. Wyden says, the framework of the new policy has an “absence of clear rules about what commercially available information can and cannot be purchased by the intelligence community.” Sen. Wyden adds that this absence “reinforces the need for Congress to pass legislation protecting the rights of Americans.” In other words, the Senate must pass the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, which would subject purchased data to the same standard as any other personal information – a probable cause warrant. That alone would clarify all the rules of the intelligence community. The risks and benefits of reverse searches are revealed in the capital murder case of Aaron Rayshan Wells. Although a security camera recorded a number of armed men entering a home in Texas where a murder took place, the lower portions of the men’s faces were covered. Wells was identified in this murder investigation by a reverse search enabled by geofencing.

A lower court upheld the geofence in this case as sufficiently narrow. It was near the location of a homicide and was within a precise timeframe on the day of the crime, 2:45-3:10 a.m. But ACLU in a recent amicus brief identifies dangers with this reverse search, even within such strict limits. What are the principles at stake in this practice? Let’s start with the Fourth Amendment, which places hurdles government agents must clear before obtaining a warrant for a search – “no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.” The founders’ tight language was formed by experience. In colonial times, the King’s agents could act on a suspicion of smuggling by ransacking the homes of all the shippers in Boston. Forcing the government to name a place, and a person or thing to be seized and searched, was the founders’ neat solution to outlawing such general warrants altogether. It was an ingenious system, and it worked well until Michael Dimino came along. In 1995, this inventor received a patent for using GPS to locate cellphones. Within a few years, geofencing technology could instantly locate all the people with cellphones within a designated boundary at a specified time. This was a jackpot for law enforcement. If a bank robber was believed to have blended into a crowd, detectives could geofence that area and collect the phone numbers of everyone in that vicinity. Make a request to a telecom service provider, run computer checks on criminals with priors, and voilà, you have your suspect. Thus the technology-enabled practice of conducting a “reverse search” kicked into high gear. Multiple technologies assist in geofenced investigations. One is a “tower dump,” giving law enforcement access to records of all the devices connected to a specified cell tower during a period of time. Wi-Fi is also useful for geofencing. When people connect their smartphones to Wi-Fi networks, they leave an exact log of their physical movements. Our Wi-Fi data also record our online searches, which can detail our health, mental health, and financial issues, as well intimate relationships, and political and religious activities and beliefs. A new avenue for geofencing was created on Monday by President Biden when he signed into a law a new measure that will give the government the ability to tap into data centers. The government can now enlist the secret cooperation of the provider of “any” service with access to communications equipment. This gives the FBI, U.S. intelligence agencies, and potentially local law enforcement a wide, new field with which to conduct reverse searches based on location data. In these ways, modern technology imparts an instant, all-around understanding of hundreds of people in a targeted area, at a level of intimacy that Colonel John André could not have imagined. The only mystery is why criminals persist in carrying their phones with them when they commit crimes. Google was law enforcement’s ultimate go-to in geofencing. Warrants from magistrates authorizing geofence searches allowed the police to obtain personal location data from Google about large numbers of mobile-device users in a given area. Without any further judicial oversight, the breadth of the original warrant was routinely expanded or narrowed in private negotiations between the police and Google. In 2023, Google ended its storage of data that made geofencing possible. Google did this by shifting the storage of location data from its servers to users’ phones. For good measure, Google encrypted this data. But many avenues remain for a reverse search. On one hand, it is amazing that technology can so rapidly identify suspects and potentially solve a crime. On the other, technology also enables dragnet searches that pull in scores of innocent people, and potentially makes their personal lives an open book to investigators. ACLU writes: “As a category, reverse searches are ripe for abuse both because our movements, curiosity, reading, and viewing are central to our autonomy and because the process through which these searches are generally done is flawed … Merely being proximate to criminal activity could make a person the target of a law enforcement investigation – including an intrusive search of their private data – and bring a police officer knocking on their door.” Virginia judge Mary Hannah Lauck in 2022 recognized this danger when she ruled that a geofence in Richmond violated the Fourth Amendment rights of hundreds of people in their apartments, in a senior center, people driving by, and in nearby stores and restaurants. Judge Lauck wrote “it is difficult to overstate the breadth of this warrant” and that an “innocent individual would seemingly have no realistic method to assert his or her privacy rights tangled within the warrant. Geofence warrants thus present the marked potential to implicate a ‘right without a remedy.’” ACLU is correct that reverse searches are obvious violations of the plain meaning of the Fourth Amendment. If courts continue to uphold this practice, however, strict limits need to be placed on the kinds of information collected, especially from the many innocent bystanders routinely caught up in geofencing and reverse searches. And any change in the breadth of a warrant should be determined by a judge, not in a secret deal with a tech company. PPSA Calls on Senate to End Data Purchases The House voted 219-199 to pass the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, which requires the FBI and other federal agencies to obtain a warrant before they can purchase Americans’ personal data, including internet records and location histories.

“Every American should celebrate this strong victory in the House of Representatives today,” said Bob Goodlatte, former House Judiciary Chairman and PPSA Senior Policy Advisor. “We commend the House for stepping up to protect Americans from a government that asserts a right to purchase the details of our daily lives from shady data brokers. This vote serves notice on the government that a new day is dawning. It is time for the intelligence community to respect the will of the American people and the authority of the Fourth Amendment.” Federal agencies, from the FBI to the IRS, ATF, and the Departments of Defense and Homeland Security, for years have purchased Americans’ sensitive, personal information scraped from apps and sold by data brokers. This practice is authorized by no specific statute, nor conducted under any judicial oversight. “The Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act puts an end to the peddling of Americans’ private lives to the government,” said Gene Schaerr, general counsel of PPSA. “Eighty percent of the American people in a recent YouGov poll say they believe warrants are absolutely necessary before their digital lives can be reviewed by the government. It is now the duty of the U.S. Senate to finish the job and express the will of the people.” PPSA is grateful to Rep. Warren Davidson, House Judiciary Chairman Jim Jordan, Ranking Member Jerry Nadler, Reps. Andy Biggs, Rep. Pramila Jayapal, Rep. Zoe Lofgren, Rep. Thomas Massie, Rep. Sara Jacobs, and many others who worked to persuade Members to pass this bill in such a strong bipartisan victory. Much of the credit also goes to PPSA’s followers, thousands of whom called and emailed Members of the House at a critical time. “We will need you again when the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act goes to the Senate,” Schaerr said. “Stay tuned.” Forbes reports that federal authorities were granted a court order to require Google to hand over the names, addresses, phone numbers, and user activities of internet surfers who were among the more than 30,000 viewers of a post. The government also obtained access to the IP addresses of people who weren’t logged onto the targeted account but did view its video.

The post in question is suspected of being used to promote the sale of bitcoin for cash, which would be a violation of money-laundering rules. The government likely had good reason to investigate that post. But did it have to track everyone who came into contact with it? This is a prime example of the government’s street-sweeper shotgun approach to surveillance. We saw this when law enforcement in Virginia tracked the location histories of everyone in the vicinity of a robbery. A state judge later found that search meant that everyone in the area, from restaurant patrons to residents of a retirement home, had “effectively been tailed.” We saw the government shotgun approach when the FBI secured the records of everyone in the Washington, D.C., area who used their debit or credit cards to make Bank of America ATM withdrawals between Jan. 5 and Jan. 7, 2021. We also saw it when the FBI, searching for possible foreign influence in a congressional campaign, used FISA Section 702 data – meant to surveil foreign threats on foreign soil – to pull the data of 19,000 political donors. Surfing the web is not inherently suspicious. What we watch online is highly personal, potentially revealing all manner of social, romantic, political, and religious beliefs and activities. The Founders had such dragnet-style searches precisely in mind when they crafted the Fourth Amendment. Simply watching a publicly posted video is not by itself probable cause for search. It should not compromise one’s Fourth Amendment rights. Byron Tau – journalist and author of Means of Control, How the Hidden Alliance of Tech and Government Is Creating a New American Surveillance State – discusses the details of his investigative reporting with Liza Goitein, senior director of the Brennan Center for Justice's Liberty & National Security Program, and Gene Schaerr, general counsel of the Project for Privacy and Surveillance Accountability.

Byron explains what he has learned about the shadowy world of government surveillance, including how federal agencies purchase Americans’ most personal and sensitive information from shadowy data brokers. He then asks Liza and Gene about reform proposals now before Congress in the FISA Section 702 debate, and how they would rein in these practices. “I Have to Pull Down My Pants in Order to Exercise a Constitutional Right"When Joseph Kamenshchik, an attorney in Nassau County, New York, sought a pistol license from the Nassau County Police Department, he faced an application process he described as “subjective, duplicative, overly broad and burdensome.” One requirement was for Kamenshchik to be subjected to a urinalysis test to screen for illicit drug abuse.

“I have to pull down my pants in order to exercise a constitutional right,” Kamenshchik told Samantha Max of non-profit news site Gothamist. Officials also demanded a list of Kamenshchik’s social media accounts. Ever since the U.S. Supreme Court struck down New York State’s restrictive gun permitting scheme in 2020 (New York State Rifle & Pistol Association Inc. v. Bruen), officials in that state have thrown up one roadblock after another in the application process, in an apparent effort to discourage New Yorkers from becoming legal, licensed gunowners. One state judge on Long Island didn’t buy that the state’s process was constitutionally justified. Justice James P. McCormack ruled that the Nassau County Police Department cannot require Kamenshchik to undergo testing of his urine or be forced to turn over a list of his social media accounts. “Irreparable harm exists because Kamenshchik is being denied a constitutional right,” Justice McCormack ruled. We would add that in fact two constitutional rights were violated – the imposition of an unreasonable search contrary to the Fourth Amendment, as well as discouragement of the exercise of Second Amendment rights. Even reasonable conditions for applicants in New York State are being applied in an unreasonable manner. The judge’s order asks the county to explain why it takes up to eight months to fingerprint an applicant. Justice McCormack declared: “This court wanted, and continues to want, an explanation as to why it takes so long, and why fingerprinting cannot take place at any precinct (like it can and does for other reasons.) Absent a valid reason, the court could be constrained to find the wait unreasonable and unconstitutional.” Officials in New York have every right to conduct background checks of applicants, as well as to have their fingerprints on file. But their actions show that it is their disagreement with the Supreme Court’s ruling that inspires the slow-walking of gun permit applications. Such practices veer perilously close to the old Confederacy’s doctrine of nullification. Most of all, imposing an unreasonable search of an applicant’s body chemistry or asking for access to all his or her social media activities shows blatant disrespect for the spirit and perhaps the letter of the Fourth Amendment. A federal court has given the go-ahead for a lawsuit filed by Just Futures Law and Edelson PC against Western Union for its involvement in a dragnet surveillance program called the Transaction Record Analysis Center (TRAC).

Since 2022, PPSA has followed revelations on a unit of the Department of Homeland Security that accesses bulk data on Americans’ money wire transfers above $500. TRAC is the central clearinghouse for this warrantless information, recording wire transfers sent or received in Arizona, California, New Mexico, Texas, and Mexico. These personal, financial transactions are then made available to more than 600 law enforcement agencies – almost 150 million records – all without a warrant. Much of what we know about TRAC was unearthed by a joint investigation between ACLU and Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR). In 2023, Gene Schaerr, PPSA general counsel, said: “This purely illegal program treats the Fourth Amendment as a dish rag.” Now a federal judge in Northern California determined that the plaintiffs in Just Future’s case allege plausible violations of California laws protecting the privacy of sensitive financial records. This is the first time a court has weighed in on the lawfulness of the TRAC program. We eagerly await revelations and a spirited challenge to this secretive program. The TRAC intrusion into Americans’ personal finances is by no means the only way the government spies on the financial activities of millions of innocent Americans. In February, a House investigation revealed that the U.S. Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) has worked with some of the largest banks and private financial institutions to spy on citizens’ personal transactions. Law enforcement and private financial institutions shared customers’ confidential information through a web portal that connects the federal government to 650 companies that comprise two-thirds of the U.S. domestic product and 35 million employees. TRAC is justified by being ostensibly about the border and the activities of cartels, but it sweeps in the transactions of millions of Americans sending payments from one U.S. state to another. FinCEN set out to track the financial activities of political extremists, but it pulls in the personal information of millions of Americans who have done nothing remotely suspicious. Groups on the left tend to be more concerned about TRAC and groups on the right, led by House Judiciary Chairman Jim Jordan, are concerned about the mass extraction of personal bank account information. The great thing about civil liberties groups today is their ability to look beyond ideological silos and work together as a coalition to protect the rights of all. For that reason, PPSA looks forward to reporting and blasting out what is revealed about TRAC in this case in open court. Any revelations from this case should sink in across both sides of the aisle in Congress, informing the debate over America’s growing surveillance state. The reauthorization of FISA Section 702, which allows federal agencies to conduct international surveillance for national security purposes, has languished in Congress like an old Spanish galleon caught in the doldrums. This happened after opponents of reform pulled Section 702 reauthorization from the House floor rather than risk losing votes on popular measures, such as requiring government agencies to obtain warrants before surveilling Americans’ communications.

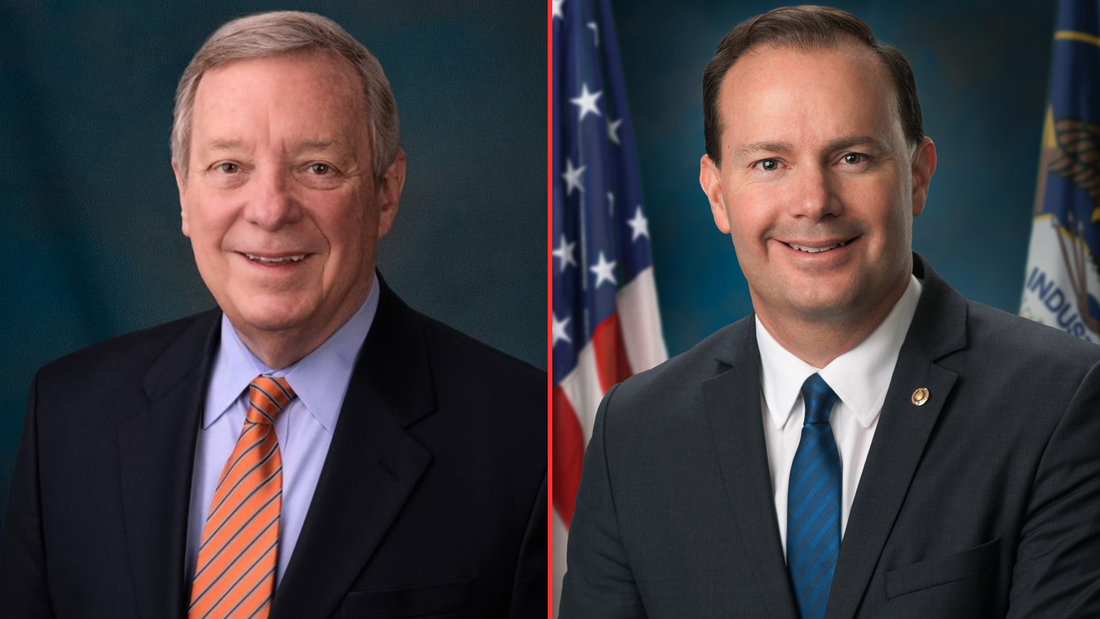

But the winds are no longer becalmed. They are picking up – and coming from the direction of reform. Sen. Dick Durbin (D-IL), Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, and fellow committee member Sen. Mike Lee (R-UT), today introduced the Security and Freedom Enhancement (SAFE) Act. This bill requires the government to obtain warrants or court orders before federal agencies can access Americans’ personal information, whether from Section 702-authorized programs or purchased from data brokers. Enacted by Congress to enable surveillance of foreign targets in foreign lands, Section 702 is used by the FBI and other federal agencies to justify domestic spying. According to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) Court, under Section 702 government “batch” searches have included a sitting U.S. Congressman, a U.S. Senator, journalists, political commentators, a state senator, and a state judge who reported civil right violations by a local police chief to the FBI. It has even been used by government agents to stalk online romantic prospects. Millions of Americans in recent years have had their communications compromised by programs under Section 702. The reforms of the SAFE Act promise to reverse this trend, protecting Americans’ privacy and constitutional rights from the government. The SAFE Act requires:

Durbin-Lee is a pragmatic bill. It lifts warrants and other requirements in emergency circumstances. The SAFE Act allows the government to obtain consent for surveillance if the subject of the search is a potential victim or target of a foreign plot. It allows queries designed to identify targets of cyberattacks, where the only content accessed and reviewed is malicious software or cybersecurity threat signatures. The SAFE Act is a good-faith effort to strike a balance between national security and Americans’ privacy. It should break the current stalemate, renewing the push for debate and votes on amendments to the reauthorization of Section 702. While Congress debates adding reforms to FISA Section 702 that would curtail the sale of Americans’ private, sensitive digital information to federal agencies, the Federal Trade Commission is already cracking down on companies that sell data, including their sales of “location data to government contractors for national security purposes.”

The FTC’s words follow serious action. In January, the FTC announced proposed settlements with two data aggregators, X-Mode Social and InMarket, for collecting consumers’ precise location data scraped from mobile apps. X-Mode, which can assimilate 10 billion location data points and link them to timestamps and unique persistent identifiers, was targeted by the FTC for selling location data to private government contractors without consumers’ consent. In February, the FTC announced a proposed settlement with Avast, a security software company, that sold “consumers’ granular and re-identifiable browsing information” embedded in Avast’s antivirus software and browsing extensions. What is the legal basis for the FTC’s action? The agency seems to be relying on Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act, which grants the FTC power to investigate and prevent deceptive trade practices. In the case of X-Mode, the FTC’s proposed complaint highlight’s X-Mode’s statement that their location data would be used solely for “ad personalization and location-based analytics.” The FTC alleges X-Mode failed to inform consumers that X-Mode “also sold their location data to government contractors for national security purposes.” The FTC’s evolving doctrine seems even more expansive, weighing the stated purpose of data collection and handling against its actual use. In a recent blog, the FTC declares: “Helping people prepare their taxes does not mean tax preparation services can use a person’s information to advertise, sell, or promote products or services. Similarly, offering people a flashlight app does not mean app developers can collect, use, store, and share people’s precise geolocation information. The law and the FTC have long recognized that a need to handle a person’s information to provide them a requested product or service does not mean that companies are free to collect, keep, use, or share that’s person’s information for any other purpose – like marketing, profiling, or background screening.” What is at stake for consumers? “Browsing and location data paint an intimate picture of a person’s life, including their religious affiliations, health and medical conditions, financial status, and sexual orientation.” If these cases go to court, the tech industry will argue that consumers don’t sign away rights to their private information when they sign up for tax preparation – but we all do that routinely when we accept the terms and conditions of our apps and favorite social media platforms. The FTC’s logic points to the common understanding that our data is collected for the purpose of selling us an ad, not handing over our private information to the FBI, IRS, and other federal agencies. The FTC is edging into the arena of the Fourth Amendment Is Not for Sale Act, which targets government purchases and warrantless inspection of Americans’ personal data. The FTC’s complaints are, for the moment, based on legal theory untested by courts. If Congress attaches similar reforms to the reauthorization of FISA Section 702, it would be a clear and hard to reverse protection of Americans’ privacy and constitutional rights. Ken Blackwell, former ambassador and mayor of Cincinnati, has a conservative resume second to none. He is now a senior fellow of the Family Research Council and chairman of the Conservative Action Project, which organizes elected conservative leaders to act in unison on common goals. So when Blackwell writes an open letter in Breitbart to Speaker Mike Johnson warning him not to try to reauthorize FISA Section 702 in a spending bill – which would terminate all debate about reforms to this surveillance authority – you can be sure that Blackwell was heard.

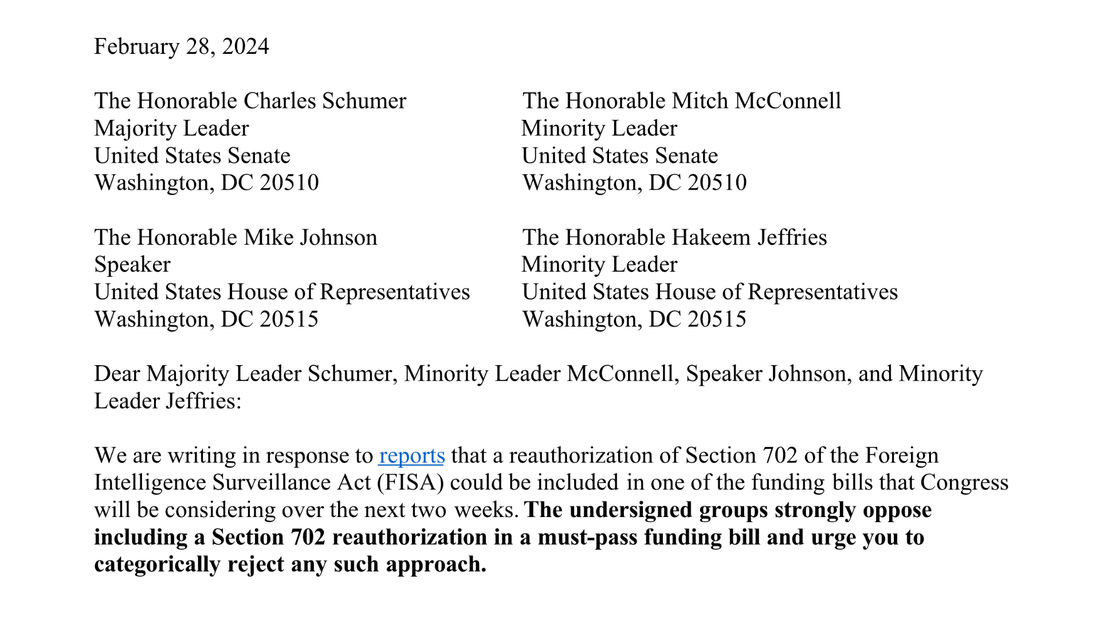

“The number of FISA searches has skyrocketed with literally hundreds of thousands of warrantless searches per year – many of which involve Americans,” Blackwell wrote. “Even one abuse of a citizen’s constitutional rights must not be tolerated. When that number climbs into the thousands, Congress must step in.” What makes Blackwell’s appeal to Speaker Johnson unique is he went beyond including the reform efforts from conservative stalwarts such as House Judiciary Committee Chairman Jim Jordan and Rep. Andy Biggs of the Freedom Caucus. Blackwell also cited the support from the committee’s Ranking Member, Rep. Jerry Nadler, and Rep. Pramila Jayapal, who heads the House Progressive Caucus. Blackwell wrote: “Liberal groups like the ACLU support reforming FISA, joining forces with conservatives civil rights groups. This reflects a consensus almost unseen on so many other important issues of our day. Speaker Johnson needs to take note of that as he faces pressure from some in the intelligence community and their overseers in Congress, who are calling for reauthorizing this controversial law without major reforms and putting that reauthorization in one of the spending bills that will work its way through Congress this month.” That is sound advice for all Congressional leaders on Section 702, whichever side of the aisle they are on. In December, members of this left-right coalition joined together to pass reform measures out of the House Judiciary Committee by an overwhelming margin of 35 to 2. This reform coalition is wide-ranging, its commitment is deep, and it is not going to allow a legislative maneuver to deny Members their right to a debate. PPSA, in concert with a coalition of major civil liberties groups from the left, right, and center, is appealing to Members of Congress “to oppose any legislative end-run that allows the FBI and other intelligence agencies to continue to spy on Americans without giving Congress the opportunity to vote on reforms.”

The word from Capitol Hill is that the intelligence community is now lobbying to attach a reauthorization of FISA Section 702 to a “must-pass” spending measure. Such a maneuver would cement the intelligence community’s strategy of denying Members of Congress a chance to have a debate and to vote on reforms to this surveillance authority. Our letter, which includes Americans for Prosperity, the Brennan Center for Justice, Demand Progress, FreedomWorks, and the Wikimedia Foundation, warns Congress: “The Fourth Amendment will become a constitutional dead letter if the government can continue to track our every movement, communications, where we worship, our financial and health issues, what we believe, and our political activity without warrants.” Our letter concludes: “Congress must be able to vote on reforms rather than being faced with a ‘take-it-or-leave-it’ choice between funding the government and protecting Americans’ liberties.” Our FISA Reform Coalition letter ended by urging Congress to stand up for Americans’ privacy, the Constitution, and against the insulting premise that Members of Congress should not be allowed to vote on surveillance reform. When we covered a Michigan couple suing their local government for sending a drone over their property to prove a zoning violation, we asked if there are any legal limits to aerial surveillance of your backyard.

In this case before the Michigan Supreme Court, Maxon v. Long Lake Township, counsel for the local government said that the right to inspect our homes goes all the way to space. He described the imaging capability of Google Earth satellites, asking: “If you want to know whether it’s 50 feet from this house to this barn, or 100 feet from this house to this barn, you do that right on the Google satellite imagery. And so given the reality of the world we live in, how can there be a reasonable expectation of privacy in aerial observations of property?” One justice reacted to the assertion that if Google Earth could map a backyard as closely and intimately as a drone, that would be a search. “Technology is rapidly changing,” the justice responded. “I don’t think it is hard to predict that eventually Google Earth will have that capacity.” Now William J. Broad of The New York Times reports that we’re well beyond Google Earth’s imaging of barns and houses. Try dinner plates and forks. Albedo Space of Denver is making a fleet of 24 small, low orbit satellites that will use imagery to guide responders in disasters, such as wildfires and other public emergencies. It will improve the current commercial standard of satellite imaging from a focal length of about a foot to about four inches. A former CIA official with decades of satellite experience told Broad that it will be a “big deal” when people realize that anything they are trying to hide in their backyards will be visible. Skinny-dipping in the pool will only be for the supremely confident. To his credit, Albedo chief Topher Haddad said, “we’re acutely aware of the privacy implications,” promising that management will be selective in their choice of clients on a case-by-case basis. It is good to know that Albedo likely won’t be using its technology to catch zone violators or backyard sunbathers. We’ve seen, however, that what is cutting-edge technology today will be standard tomorrow. This is just one more way in which the velocity of technology is outpacing our ability to adjust. There is, of course, one effective response. We can reject the Michigan town’s counsel argument who said, essentially, that privacy’s dead and we should just get over it. Courts and Congress should define orbital and aerial surveillance as searches requiring a probable cause warrant, as defined by the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, before our homes and backyards can be invaded by eyes from above. The greatest danger to privacy is not that Albedo will allow government snoops to watch us in real time. The real threat is a satellite company’s ability to collect private images by the tens of millions. Such a database could then be sold to the government just as so much commercial digital information is now being sold to the government by data brokers. This is all the more reason for Congress to import the privacy-protecting warrant provisions of the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act into the reauthorization of FISA Section 702. Just in time for the Section 702 debate, Emile Ayoub and Elizabeth Goitein of the Brennan Center for Justice have written a concise and easy to understand primer on what the data broker loophole is about, why it is so important, and what Congress can do about it.

These authors note that in this age of “surveillance capitalism” – with a $250 billion market for commercial online data – brokers are compiling “exhaustive dossiers” that “reveal the most intimate details of our lives, our movements, habits, associations, health conditions, and ideologies.” This happens because data brokers “pay app developers to install code that siphons users’ data, including location information. They use cookies or other web trackers to capture online activity. They scrape from information public-facing sites, including social media platforms, often in violation of those platforms’ terms of service. They also collect information from public records and purchase data from a wide range of companies that collect and maintain personal information, including app developers, internet service providers, car manufacturers, advertisers, utility companies, supermarkets, and other data brokers.” Armed with all this information, data brokers can easily “reidentify” individuals from supposedly “anonymized” data. This information is then sold to the FBI, IRS, the Drug Enforcement Administration, the Department of Defense, the Department of Homeland Security, and state and local law enforcement. Ayoub and Goitein examine how government lawyers employ legal sophistry to evade a U.S. Supreme Court ruling against the collection of location data, as well as the plain meaning of the U.S. Constitution, to access Americans’ most personal and sensitive information without a warrant. They describe the merits of the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, and how it would shut down “illegitimately obtained information” from companies that scrape photos and data from social media platforms. The latter point is most important. Reformers in the House are working hard to amend FISA Section 702 with provisions from the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, to require the government to obtain warrants before inspecting our commercially acquired data. While the push is on to require warrants for Americans’ data picked up along with international surveillance, the job will be decidedly incomplete if the government can get around the warrant requirement by simply buying our data. Ayoub and Goitein conclude that Congress must “prohibit government agencies from sidestepping the Fourth Amendment.” Read this paper and go here to call your House Member and let them know that you demand warrants before the government can access our sensitive, personal information. The word from Capitol Hill is that Speaker Mike Johnson is scheduling a likely House vote on the reauthorization of FISA’s Section 702 this week. We are told that proponents and opponents of surveillance reform will each have an opportunity to vote on amendments to this statute.

It is hard to overstate how important this upcoming vote is for our privacy and the protection of a free society under the law. The outcome may embed warrant requirements in this authority, or it may greatly expand the surveillance powers of the government over the American people. Section 702 enables the U.S. intelligence community to continue to keep a watchful eye on spies, terrorists, and other foreign threats to the American homeland. Every reasonable person wants that, which is why Congress enacted this authority to allow the government to surveil foreign threats in foreign lands. Section 702 authority was never intended to become what it has become: a way to conduct massive domestic surveillance of the American people. Government agencies – with the FBI in the lead – have used this powerful, invasive authority to exploit a backdoor search loophole for millions of warrantless searches of Americans’ data in recent years. In 2021, the secret Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court revealed that such backdoor searches are used by the FBI to pursue purely domestic crimes. Since then, declassified court opinions and compliance reports reveal that the FBI used Section 702 to examine the data of a House Member, a U.S. Senator, a state judge, journalists, political commentators, 19,000 donors to a political campaign, and to conduct baseless searches of protesters on both the left and the right. NSA agents have used it to investigate prospective and possible romantic partners on dating apps. Any reauthorization of Section 702 must include warrants – with reasonable exceptions for emergency circumstances – before the data of Americans collected under Section 702 or any other search can be queried, as required by the U.S. Constitution. This warrant requirement must include the searching of commercially acquired information, as well as data from Americans’ communications incidentally caught up in the global communications net of Section 702. The FBI, IRS, Department of Homeland Security, the Pentagon, and other agencies routinely buy Americans’ most personal, sensitive information, scraped from our apps and sold to the government by data brokers. This practice is not authorized by any statute, or subject to any judicial review. Including a warrant requirement for commercially acquired information as well as Section 702 data is critical, otherwise the closing of the backdoor search loophole will merely be replaced by the data broker loophole. If the House declines to impose warrants for domestic surveillance, expect many politically targeted groups to have their privacy and constitutional rights compromised. We cannot miss the best chance we’ll have in a generation to protect the Constitution and what remains of Americans’ privacy. Copy and paste the message below and click here to find your U.S. Representative and deliver it: “Please stand up for my privacy and the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Vote to reform FISA’s Section 702 with warrant requirements, both for Section 702 data and for our sensitive, personal information sold to government agencies by data brokers.” Late last year, Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR) put a hold on the appointment of Lt. Gen. Timothy Haugh to replace outgoing National Security Agency director Gen. Paul Nakasone. Late Thursday, Sen. Wyden’s pressure campaign yielded a stark result – a frank admission from Gen. Nakasone that, as long suspected, the NSA purchases Americans’ sensitive, personal online activities from commercial data brokers.

The NSA admitted it buys netflow data, which records connections between computers and servers. Even without the revelation of messages’ contents, such tracking can be extremely personal. A Stanford University study of telephone metadata showed that a person’s calls and texts can reveal connections to sensitive life issues, from Alcoholics Anonymous to abortion clinics, gun stores, mental and health issues including sexually transmitted disease clinics, and connections to faith organizations. Gen. Nakasone’s letter to Sen. Wyden states that NSA works to minimize the collection of such information. He writes that NSA does not buy location information from phones inside the United States, or purchase the voluminous information collected by our increasingly data-hungry automobiles. It would be a mistake, however, to interpret NSA’s internal restrictions too broadly. While NSA is generally the source for signals intelligence for the other agencies, the FBI, IRS, and the Department of Homeland Security are known to make their own data purchases. In 2020, PPSA reported on the Pentagon purchasing data from Muslim dating and prayer apps. In 2021, Sen. Wyden revealed that the Defense Intelligence Agency was purchasing Americans’ location data from our smartphones without a warrant. How much data, and what kinds of data, are purchased by the FBI is not clear. Sen. Wyden did succeed in a hearing last March in prompting FBI Director Christopher Wray to admit that the FBI had, in some period in the recent past, purchased location data from Americans’ smartphones without a warrant. Despite a U.S. Supreme Court opinion, Carpenter (2018), which held that the U.S. Constitution requires a warrant for the government to compel telecom companies to turn over Americans’ location data, federal agencies maintain that the Carpenter standard does not curb their ability to purchase commercially available digital information. In a press statement, Sen. Wyden hammers home the point that a recent Federal Trade Commission order bans X-Mode Social, a data broker, and its successor company, from selling Americans’ location data to government contractors. Another data broker, InMarket Media, must notify customers before it can sell their precise location data to the government. We now have to ask: was Wednesday’s revelation that the Biden Administration is drafting rules to prevent the sale of Americans’ data to hostile foreign governments an attempt by the administration to partly get ahead of a breaking story? For Americans concerned about privacy, the stakes are high. “Geolocation data can reveal not just where a person lives and whom they spend time with but also, for example, which medical treatments they seek and where they worship,” FTC Chair Lina Khan said in a statement. “The FTC’s action against X-Mode makes clear that businesses do not have free license to market and sell Americans’ sensitive location data. By securing a first-ever ban on the use and sale of sensitive location data, the FTC is continuing its critical work to protect Americans from intrusive data brokers and unchecked corporate surveillance.” As Sen. Wyden’s persistent digging reveals more details about government data purchases, Members of Congress are finding all the more reason to pass the Protect Liberty Act, which enforces the Constitution’s Fourth Amendment warrant requirement when the government inspects Americans’ purchased data. This should also put Members of the Senate and House Intelligence Committees on the spot. They should explain to their colleagues and constituents why they’ve done nothing about government purchases of Americans’ data – and why their bills include exactly nothing to protect Americans’ privacy under the Fourth Amendment. More to come … No sooner did the Protect Liberty and End Warrantless Surveillance Act pass the House Judiciary Committee with overwhelming bipartisan support than the intelligence community began to circulate what Winston Churchill in 1906 politely called “terminological inexactitudes.”

The Protect Liberty Act is a balanced bill that respects the needs of national security while adding a warrant requirement whenever a federal agency inspects the data or communications of an American, as required by the Fourth Amendment. This did not stop defenders of the intelligence community from claiming late last year that Section 702 reforms would harm the ability of the U.S. government to fight fentanyl. This is remarkable, given that the government hasn’t cited a single instance in which warrantless searches of Americans’ communications proved useful in combating the fentanyl trade. Nothing in the bill would stop surveillance of factories in China or cartels in Mexico. If an American does become a suspect in this trafficking, the government can and should seek a probable cause warrant, as is routinely done in domestic law enforcement cases. No sooner did we bat that one away than we heard about fresh terminological inexactitudes. Here are two of the latest bits of disinformation being circulated on Capitol Hill about the Protect Liberty Act. Intelligence Community Myth: Members of Congress are being told that under the Protect Liberty Act, the FBI would be forced to seek warrants from district court judges, who might or might not have security clearances, in order to perform U.S. person queries. Fact: The Protect Liberty Act allows the FBI to conduct U.S. person queries if it has either a warrant from a regular federal court or a probable cause order from the FISA Court, where judges have high-level security clearances. The FBI will determine which type of court order is appropriate in each case. Intelligence Community Myth: Members are being told that under the Protect Liberty Act, terrorists can insulate themselves from surveillance by including a U.S. person in a conversation or email thread. Fact: Under the Protect Liberty Act, the FBI can collect any and all communications of a foreign target, including their communications with U.S. persons. Nothing in the bill prevents an FBI agent from reviewing U.S. person information the agent encounters in the course of reviewing the foreign target’s communications. In other words, if an FBI agent is reading a foreign target’s emails and comes across an email to or from a U.S. person, the FBI agent does not need a warrant to read that email. The bill’s warrant requirement applies in one circumstance only: when an FBI agent runs a query designed to retrieve a U.S. person’s communications or other Fourth Amendment-protected information. That is as it should be under the U.S. Constitution. As we face the renewed debate over Section 702 – which must be reauthorized in the next few months – expect the parade of untruths to continue. As they do, PPSA will be here to call them out. The American Civil Liberties Union, its Northern California chapter, and the Brennan Center, are calling on the Federal Trade Commission to investigate whether Meta and X have broken commitments they made to protect customers from data brokers and government surveillance.

This concern goes back to 2016 when it came to light that Facebook and Twitter helped police target Black Lives Matter activists. As a result of protests by the ACLU of Northern California and other advocacy groups, both companies promised to strengthen their anti-surveillance policies and cut off access to social media surveillance companies. Their privacy promises even became points of pride in these companies’ advertising. Now ACLU and Brennan say they have uncovered commercial documents from data brokers that seem to contradict these promises. They point to a host of data companies that publicly claim they have access to data from Meta and/or X, selling customers’ information to police and other government agencies. ACLU writes: “These materials suggest that law enforcement agencies are getting deep access to social media companies’ stores of data about people as they go about their daily lives.” While this case emerged from left-leaning organizations and concerns, organizations and people on the right have just as much reason for concern. The posts we make, what we say, who our friends are, can be very sensitive and personal information. “Something’s not right,” ACLU writes. “If these companies can really do all that they advertise, the FTC needs to figure out how.” At this point, we simply don’t know with certainty which, if any, social media platforms are permitting data brokers to obtain personal information from their platforms – information that can then be sold to the government. Regardless of the answer to that question, PPSA suggests that a thorough way to short-circuit any extraction of Americans’ most sensitive and personal information from data sales (at least at the federal level) would be to pass the strongly bipartisan Protect Liberty and End Warrantless Surveillance Act. This measure would force federal government agencies to obtain a warrant – as they should anyway under the Fourth Amendment – to access the data of an American citizen. A letter of protest sent by the lawyers of Rabbi Levi Illulian in August alleged that city officials of Beverly Hills, California, had investigated their client’s home for hosting religious gatherings for his family, neighbors, and friends. Worse, the city used increasingly invasive means, including surveilling people visiting the rabbi’s home, and flying a surveillance drone over his property.

A “notice of violation” from the city specifically threatened Illulian with civil and criminal proceedings for “religious activity” at his home. The notice further prohibited all religious activity at Illulian’s home with non-residents. With support from First Liberty Institute, the rabbi’s lawyers sent another letter detailing an egregious use of city resources to launch a “full-scale investigation against Rabbi Illulian” in which “city personnel engaged in multiple stakeouts of the home over many hours, effectively maintaining a governmental presence outside Rabbi Illulian’s home.” The rabbi’s Orthodox Jewish friends and family who visited his home had also received parking citations. The rabbi began to receive visits from the police for noise disturbances, such as on Halloween when other houses on the street were sources of noise as well. Police even threatened to charge Rabbi Illulian with a misdemeanor, confiscate his music equipment, and cite a visiting musician for violating the city’s noise ordinance, despite the obvious double-standard. First Liberty was active in publicizing the city’s actions. In the face of bad publicity about this aggressive enforcement, the city withdrew its violation notice late last year. That the city of Beverly Hills would blatantly monitor and harass a household over Shabbat prayers and religious holidays, particularly at a time of rising antisemitism, is made all the worse by sophisticated forms of surveillance aimed at the free exercise of religion. So city officials managed to abuse the Fourth Amendment to impinge on the First Amendment. This case is reminiscent of the surveillance of a church, Calvary Chapel San Jose, by Santa Clara, California, county officials, over its Covid-19 policies. Is there something about religious observances that attracts the ire of some local officials? Whatever their reasons, this story is the latest example of the need for local officials who are better acquainted with the Constitution. Just before Congress punted – delaying debate over reform proposals to Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Act – Sen. Mike Lee (R-UT) took to the Senate floor to describe how much is at stake for Americans.

Sen. Lee did not mince his words, saying Section 702 “is widely, infamously, severely abused” as “hundreds of thousands of American citizens have become victims of …warrantless backdoor searches.” The senator’s frustration boiled over when he spoke of questioning FBI directors in hearings, being told by them “don’t worry” because the FBI has strong procedures in place to prevent abuses. “We’re professionals,” they said. These promises from FBI directors, Sen. Lee said, are “like a curse,” an indication that the violation of Americans’ civil rights “gets worse every single time they say it.” The good news is that, although champions of reform fell short in Thursday’s vote, 35 senators in both parties were so bothered by the extension of Section 702 in its current form that they voted against its inclusion in the National Defense Authorization Act. What appears to be a temporary extension of Section 702 leaves the door open, we hope, for a fuller debate and vote on reform provisions early next year. When that happens, Sen. Lee will surely be in the lead. Here is the bipartisan honor roll of senators who voted in favor of surveillance reform. Tammy Baldwin (D-WI), Marsha Blackburn (R-TN), Cory Booker (D-NJ), Mike Braun (R-IN), Sherrod Brown (D-OH), Maria Cantwell (D-WA), Kevin Cramer (R-ND), Steve Daines (R-MT), Dick Durbin (D-IL), Chuck Grassley (R-IA), Bill Hagerty (R-TN), Josh Hawley (R-MO), Martin Heinrich (D-NM), Mazie Hirono (D-HI), John Hoeven (R-ND), Ron Johnson (R-WI), Mike Lee (R-UT), Ben Ray Lujan (D-NM), Cynthia Lummis (R-WY), Ed Markey (D-MA), Roger Marshall (R-KS), Robert Menendez (D-NJ), Jeff Merkley (D-OR), Rand Paul (R-KY), Bernie Sanders (I-VT), Eric Schmitt (R-MO), Rick Scott (R-FL), John Tester (D-MT),Tommy Tuberville (R-AL), Chris Van Hollen (D-MD), J.D. Vance (R-OH), Raphael Warnock (D-GA), Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), Peter Welch (D-VT), and Ron Wyden (D-OR). The House Judiciary Committee today passed the Protect Liberty and End Warrantless Surveillance Act with an overwhelmingly bipartisan vote.

Unlike competing proposals – such as the FISA Reform and Reauthorization Act now before the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (HPSCI) – the Protect Liberty Act mandates a robust warrant requirement for U.S. person searches under FISA Section 702. It curtails the common government surveillance technique of “reverse targeting” – using FISA’s Section 702 authority to work backwards to target Americans without a warrant. The Protect Liberty Act adopts language from the Fourth Amendment Is Not for Sale Act. This language closes the loophole that allows government agencies to buy access to Americans’ most sensitive and personal information scraped from apps and sold by data brokers. The Protect Liberty Act also requires amicus participation in FISA cases to protect the public and the Constitution, ensuring that the secret FISA Court will hear from civil liberties experts as well as government attorneys. And the bill would require FBI agents seeking search orders to testify to the accuracy of their reasons for bringing the search. In contrast, the competing FISA Reform and Reauthorization Act emerging from HPSCI has a weak warrant requirement that would not stop the widespread practice of backdoor searches of Americans’ information. And it does not address the outrageous practice of federal agencies buying up Americans’ most sensitive and private information from data brokers. The contrast between these two bills could not be starker. Ranking Member Jerry Nadler (D-NY) said the Protect Liberty Act is the only one of these two bills “that can pass on a floor vote.” House Judiciary Chairman Jim Jordan says he expects a floor vote next week. PPSA applauds the committee for passing this bill with such strong, bipartisan support. We are grateful to committee Chairman Jim Jordan (R-OH), Ranking Member Jerry Nadler (D-NY), Rep. Andy Biggs (R-AZ) (who introduced the bill), Rep. Sara Jacobs (D-CA), Rep. Russell Fry (R-SC), Rep. Ted Lieu (D-CA), Rep. Eli Crane (R-AZ), as well as leaders of the House Freedom Caucus and Progressive Caucus, Reps Warren Davidson (R-OH) and Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA). PPSA is also grateful to all the Members of the House Judiciary Committee who offered helpful amendments to strengthen the bill. PPSA will follow this fast-moving story. |

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed