|

We’ve long chronicled the downward trajectory of EO 13526, President Barack Obama’s 2009 executive order that boldly sought to stem the tide of excessive government secrecy. President Obama imposed checks on the government by forbidding classification decisions that are made to prevent embarrassment to a person, organization, or agency, and by boosting the ability of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) to lead a declassification program.

“My administration is committed to operating with an unprecedented level of openness,” the president declared. At the time President Obama swept his pen over this order, there were 55 million classified documents. And how has that worked out? Today 75 million classified documents have piled up. Some of them date back to the Truman administration. A report released Tuesday by the National Coalition for History makes public the inside grips of NARA in trying to fulfill its mission. The report states that NARA’s flatlined budget leaves its National Declassification Center (NDC) short-staffed and unable to cope with thousands of pending Freedom of Information Act requests. We filed one such FOIA of our own asking a slew of federal agencies in effect if “they’ve done anything to comply with President Obama’s executive order?” Some FOIAs, the History Coalition reports, sit in 12-year queues. But the bigger problems for declassification involve perverse incentives. The History Coalition reports: “Even highly skilled and experienced NDC staffers lack the authority to reverse agency decisions that they disagree with, a dynamic that perpetuates the over-classification problem.” No one ever got fired for refusing to declassify something. No one should be surprised, then, that when you ask the agency that classified a document if it should remain classified, the answer will almost always be “yes.” Another revelation from the History Coalition’s report is that the NDC lacks a secure electronic transmittal system to send classified records for agency referrals. Instead, they are sent on digitized diskettes through regular U.S. mail. You would think that if a document is so sensitive it must remain secret that sending it back with a postage stamp would be a non-starter. That laxity, more than anything, is a sure sign that what is at work isn’t the protection of vital national secrets, but bureaucratic backside covering, the only perpetual motion machine known to physics. What can be done? A good place to start is the History Coalition’s reform proposal to vest the NDC “with the authority to declassify information subject to automatic declassification without having to refer the records back to the originating agency.” Sounds like a good idea to us. The Quick Unlocking of Would-Be Trump Assassin’s Phone Reveals Power of Commercial Surveillance7/18/2024

Since 2015, Apple’s refusal to grant the FBI a backdoor to its encrypted software on the iPhone has been a matter of heated debate. When William Barr was the U.S. Attorney General, he accused Apple of failing to provide “substantive assistance” in the aftermath of mass shootings by helping the FBI break into the criminals’ phones.

Then in a case in 2020, the FBI announced it had broken into an Apple phone in just such a case. Barr said: “Thanks to the great work of the FBI – and no thanks to Apple …” Clearly, the FBI had found a workaround, though it took the bureau months to achieve it. Gaby Del Valle in The Verge offers a gripping account of the back-and-forth between law enforcement and technologists resulting, she writes, in the widespread adoption of mobile device extraction tools that now allow police to easily break open mobile phones. It was known that this technology, often using Israeli-made Cellebrite software, was becoming ever-more prolific. Still, observers did a double-take when the FBI announced that its lab in Quantico, Virginia, was able to break into the phone of Thomas Matthew Crooks, who tried to assassinate former President Trump on Saturday, in just two days. More than 2,000 law enforcement agencies in every state had access to such mobile device extraction tools as of 2020. The most effective of these tools cost between $15,000 and $30,000. It is likely, as with cell-site simulators that can spoof cellphones into giving up their data, that these phone-breaking tools are purchased by state and local law enforcement with federal grants. We noticed recently that Tech Dirt reported that for $100,000 you could have purchased a cell-site simulator of your very own on eBay. The model was old, vintage 2004, and is not likely to work well against contemporary phones. No telling what one could buy in a more sophisticated market. The takeaway is that the free market created encryption and privacy for customer safety, privacy, and convenience. The ingenuity of technologists responding to market demand from government agencies is now being used to tear down consumer encryption, one of their greatest achievements. Last year, we reported on “mail covers” – the practice of the U.S. Postal Service producing for other government agencies images of the exterior portions of envelopes to track communications between Americans. Now an exclusive in The Washington Post puts some meat on those bones.

Since 2015, postal inspectors have approved over 60,000 requests from federal agents and police officers to monitor snail mail. The Post Office approves these surveillance requests, issued without a court order, 97 percent of the time. Most of the requests come from the FBI, the IRS, and the Department of Homeland Security. Things could be worse: at one time, the Church Committee investigations of the 1970s found that the CIA had photographed the exterior portions of 2 million letters, and opened hundreds of thousands of them. In the early days of the Republic, Thomas Jefferson had so little trust in the post office that he devised an encryption scheme, which was used to share early drafts of the Bill of Rights with James Madison. The government stoutly defends this program today as legal. An 1879 U.S. Supreme Court ruling held that a warrant is needed to open an envelope, leaving open the inference that what is written on the surface of an envelope itself is fair game. This ongoing practice underscores a critical gap in privacy protections, where even the exteriors of our letters and packages can reveal much about our personal lives. Eight senators wrote the inspector general of the postal service last year objecting to this practice. “While mail covers do not reveal the contents of correspondence, they can reveal deeply personal information about Americans’ political leanings, religious beliefs, or causes they support,” the senators wrote. Senators ranging from Ron Wyden (D-OR) to Rand Paul (R-KY) are pushing for judicial oversight for these operations, aligning mail surveillance with the safeguards already required for monitoring digital communications. PPSA will track and report on their progress. The Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board (PCLOB), an independent agency since 2007, is a watchdog tasked with ensuring that federal counterterrorism programs have adequate safeguards for privacy and civil liberties.

It was only a few years ago that PCLOB was criticized for appearing more like a lapdog than a watchdog. After taking six years to study Executive Order 12333, which authorizes limited forms of surveillance outside of any statutory authority, PCLOB produced a public paper in 2021 that read like a high school book report. But under Sharon Bradford Franklin, Chair since February 2022, PCLOB has been a source of active inquiry and pinpoint distinctions that inform and enrich public debate on government surveillance. “Chair Bradford Franklin’s service is marked by balance,” said Bob Goodlatte, former Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee and Senior Policy Advisor for PPSA. “She has been a strong advocate for transparency in intelligence operations while respecting the need to enable classified programs that protect our homeland.” It was under Bradford Franklin’s leadership that the PCLOB Board reviewed the government's implementation of Presidential Policy Directive No. 28 (PPD-28), providing critical insights into how the intelligence community collects foreign intelligence. Her reports have been used by agencies as active guides on how to be both effective and compliant with the law. With the expiration of Bradford Franklin’s term as Chair, both the civil liberties community and the intelligence community should want her to be re-nominated. Her absence could disrupt critical reviews and oversight functions important to the United States and our European allies, including the review of privacy and civil liberties safeguards under Executive Order 14086 and the EU-US Data Privacy Framework. Some of our colleagues warn that the European Commission particularly values PCLOB’s oversight, and the absence of a Chair could jeopardize trans-Atlantic data flows. This one’s a no-brainer: The re-nomination of Sharon Bradford Franklin would ensure that PCLOB remains an independent watchdog that strengthens both civil liberties and national security. State financial officials in 23 states have fired off a letter to House Speaker Mike Johnson expressing strong opposition to a new Security and Exchange Commission program that grants 3,000 government employees real-time access to every equity, option trade, and quote from every account of every broker by every investor.

“Traditionally, Americans’ financial holdings are kept between them and their broker, not them, their broker, and a massive government database,” the state auditors and treasurers wrote. “The only exception has been legal investigations with a warrant." The state financial officers contend that the SEC's move undermines the principles of federalism by imposing a one-size-fits-all solution without considering the unique regulatory environments of individual states. They asked Speaker Johnson to support a bill sponsored by Rep. Barry Loudermilk (R-GA), the Protecting Investors' Personally Identifiable Information Act. This proposed legislation would restrict the SEC's ability to collect and centralize such vast amounts of personal financial data. As is so common with recent efforts at financial surveillance, the SEC justifies this data collection to combat insider trading, market manipulation, and to identify suspicious activities. Similar excuses are offered for the new “beneficial ownership” requirement that is forcing millions of Americans who own small businesses to send the ownership details of their businesses to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) of the U.S. Treasury. But such increased vigilance comes at the expense of the privacy of millions of Americans. The sheer volume of data accessible to government employees raises concerns about potential misuse and unauthorized access. “The Securities and Exchange Commission has been barreling forward with a new system – the Consolidated Audit Trail (CAT) – which tracks every trade an individual investor makes and links it to their identity through a centralized system,” Rep. Loudermilk said. “Not only is collecting all this information unnecessary, regulators already have similar systems that don’t easily match identities with transactions, but it also creates another security vulnerability and a target for hackers.” While the SEC assures lawmakers that strict safeguards are in place – given recent high-profile hacks and All the more reason for Speaker Johnson to give Rep. Loudermilk’s bill a big push on the House floor. The doxing of donors is a danger to our democracy.

When donors give to a controversial cause, they count on anonymity to protect them from public backlash. This is a principle enshrined in law since 1958, when the U.S. Supreme Court protected donors to the NAACP from forcible disclosure by the State of Alabama. Undeterred by this precedent, California tried to enforce a measure to capture the identities of donors and hold them in the office of that state’s attorney general, despite the fact that the California AG’s office has a history of leaks and data breaches. Surprisingly, the federal Ninth Circuit upheld that plan. The Project for Privacy and Surveillance Accountability filed a brief before the U.S. Supreme Court arguing that this policy is dangerous, not just to the robust practice of democracy, but to human lives. Citizens have lost their jobs, had their businesses threatened, and even been targeted for physical violence, all because they donated to a political or cultural cause. In 2021, the Supreme Court agreed with PPSA, reversing a Ninth Circuit opinion in Americans for Prosperity v. Bonta. Still, the drive to expose donors – whether progressives going after gun rights organizations or conservatives going after protest organizations – remains a hot-button issue in state politics across the country. Politicians and groups are eager to know: Is George Soros or the Koch Foundation or name-your-favorite-nemesis giving money to a cause you oppose? Thanks to the work of the People United For Privacy (PUFP) foundation, that push to expose is now stopped cold in 20 states. With help from PUFP, bipartisan coalitions in 20 states have adopted the Personal Privacy Protection Act (PPPA) to provide a shield for donor privacy by protecting their anonymity. This movement is spreading across the country, with Alabama, Colorado, and Nebraska having passed some version of this law just this year. “Every American has the right to support causes they believe in without fear of harassment or abuse of their personal information,” says Heather Lauer, who heads People United for Privacy. “The PPPA is a commonsense measure embraced by lawmakers in both parties across the ideological spectrum.” Supporters have ranged from state chapters of the ACLU, NAACP, and Planned Parenthood to pro-life groups, gun rights groups, and free market think tanks. Thanks to this campaign, 40 percent of states now protect donors. For the remaining 60 percent, the power of the internet can expose donors’ home addresses, places of work, family members, and other private information to harassers. The need to enact this law in the remaining 30 states is urgent. Still, securing donor protection in 20 states is a remarkable record given that People United for Privacy was only founded in 2018. We look forward to supporting their efforts and seeing more wins for privacy in the next few years. George Orwell wrote that in a time of deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act.

Revolutionary acts of truth-telling are becoming progressively more dangerous around the world. This is especially true as autocratic countries and weak democracies purchase AI software from China to weave together surveillance technology to comprehensively track individuals, following them as they meet acquaintances and share information. A piece by Abi Olvera posted by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists describes this growing use of AI to surveil populations. Olvera reports that by 2019, 56 out of 176 countries were already using artificial intelligence to weave together surveillance data streams. These systems are increasingly being used to analyze the actions of crowds, track individuals across camera views, and pierce the use of masks or scramblers intended to disguise faces. The only impediment to effective use of this technology is the frequent Brazil-like incompetence of domestic intelligence agencies. Olvera writes: “Among other things, frail non-democratic governments can use AI-enabled monitoring to detect and track individuals and deter civil disobedience before it begins, thereby bolstering their authority. These systems offer cash-strapped autocracies and weak democracies the deterrent power of a police or military patrol without needing to pay for, or manage, a patrol force …” Olvera quotes AI surveillance expert Martin Beraja that AI can enable autocracies to “end up looking less violent because they have better technology for chilling unrest before it happens.” Olivia Solon of Bloomberg reports on the uses of biometric identifiers in Africa, which are regarded by the United Nations and World Bank as a quick and easy way to establish identities where licenses, passports, and other ID cards are hard to come by. But in Uganda, Solon reports, President Yoweri Museveni – in power for 40 years – is using this system to track his critics and political opponents of his rule. Used to catch criminals, biometrics is also being used to criminalize Ugandan dissidents and rival politicians for “misuse of social media” and sharing “malicious information.” The United States needs to lead by example. As our facial recognition and other systems grow in ubiquity, Congress and the states need to demonstrate our ability to impose limits on public surveillance, and legal guardrails for the uses of the sensitive information they generate. In the early 1920s revenue agents staked out a South Carolina home the agents suspected was being used as a distribution center for moonshine whiskey. The revenue agents were in luck. They saw a visitor arrive to receive a bottle from someone inside the house. The agents moved in. The son of the home’s owner, a man named Hester, realized that he was about to be arrested and sprinted with the bottle to a nearby car, picked up a gallon jug, and ran into an open field.

One of the agents fired a shot into the air, prompting Hester to toss the jug, which shattered. Hester then threw the bottle in the open field. Officers found a large fragment of the broken jug and the discarded bottle both contained moonshine whiskey. This was solid proof that moonshine was being sold. But was it admissible as evidence? After all, the revenue agents did not have a warrant. This case eventually wound its way to the Supreme Court. In 1924, a unanimous Court, presided over by Chief Justice (and former U.S. President) William Howard Taft, held that the Fourth Amendment did not apply to this evidence. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, writing the Court’s opinion, declared that “the special protection accorded by the Fourth Amendment to the people in their ‘persons, houses, papers and effects,’ is not extended to the open field.” This principle was later extended to exclude any garbage that a person throws away from Fourth Amendment protections. As strange as it may seem, this case about broken jugs and moonshine from the 1920s, Hester v. United States, provides the principle by which law enforcement officers freely help themselves to the information inside a discarded or lost cellphone – text messages, emails, bank records, phone calls, and images. We reported a case in 2022 in which a Virginia man was convicted of crimes based on police inspection of a cellphone he had left behind in a restaurant. That man’s attorney, Brandon Boxler, told the Daily Press of Newport News that “cellphones are different. They have massive storage capabilities. A search of a cellphone involves a much deeper invasion of privacy. The depth and breadth of personal and private information they contain was unimaginable in 1924.” In Riley v. California, the Supreme Court in 2018 upheld that a warrant was required to inspect the contents of a suspect’s cellphone. But the Hester rule still applies to discarded and lost phones. They are still subject to what Justice Holmes called the rules of the open field. The American Civil Liberties Union, ACLU Oregon, the Electronic Privacy Information Center, and other civil liberties organizations are challenging this doctrine before the Ninth Circuit in Hunt v. United States. They told the court that it should not use the same reasoning that has historically applied to garbage left out for collection and items discarded in a hotel wastepaper basket. “Our cell phones provide access to information comparable in quantity and breadth to what police might glean from a thorough search of a house,” ACLU said in a posted statement. “Unlike a house, though, a cell phone is relatively easy to lose. You carry it with you almost all the time. It can fall between seat cushions or slip out of a loose pocket. You might leave it at the check-out desk after making a purchase or forget it on the bus as you hasten to make your stop … It would be absurd to suggest that a person intends to open up their house for unrestrained searches by police whenever they drop their house key.” Yet that is the government position on lost and discarded cellphones. PPSA applauds and supports the ACLU and its partners for taking a strong stand on cellphone privacy. The logic of extending special protections to cellphones, which the Supreme Court has held contain the “privacies of life,” is obvious. It is the government’s position that tastes like something cooked up in a still. Katie King in the Virginian-Pilot reports an in-depth account about the growing dependency of local law enforcement agencies on Flock Safety cameras, mounted on roads and intersections to catch drivers suspected of crimes. With more than 5,000 police agencies across the nation using these devices, the privacy implications are enormous.

Surveillance cameras have been in the news at lot lately, often in a positive light. Local news is consumed by murder suspects and porch pirates alike captured on video. The recently released video of a physical attack by rapper Sean “Diddy” Combs on a girlfriend several years ago has saturated media, reminding us that surveillance can protect the vulnerable. The crime-solving potential of license plate readers is huge. Flock’s software runs license plate numbers through law enforcement databases, allowing police to quickly track a stolen car, locate suspects fleeing a crime, or find a missing person. With such technologies, Silver and Amber alerts might one day become obsolete. As with facial recognition technology, however, license plate readers can produce false positives, ensnaring innocent people in the criminal justice system. King recounts the ordeal of an Ohio man who was arrested by police with drawn guns and a snarling dog. Flock’s license plate reader had falsely flagged his vehicle as having stolen tags. The good news is that Flock insists it is not even considering combining its network with facial recognition technology – reducing the possibility of both technologies flagging someone as dangerous. As with so many surveillance technologies, the greater issue in license-plate readers is not the technology itself, but how it might be used in a network. “There’s a simple principle that we’ve always had in this country, which is that the government doesn’t get to watch everybody all the time just in case somebody commits a crime – the United States is not China,” Jay Stanley, a senior analyst with the American Civil Liberties Union, told King. “But these cameras are being deployed with such density that it’s like GPS-tracking everyone.” License plate readers could, conceivably, be networked to track everywhere that everyone goes – from trips to mental health clinics, to gun stores, to houses of worship, and protests. With so many federal agencies already purchasing Americans’ sensitive data from data brokers, creating a national network of drivers’ whereabouts is just one more addition to what is already becoming a national surveillance system. With apologies to Jay Stanley, we are in serious danger of becoming China. As massive databases compile facial recognition, location data, and now driving routes, we need more than ever to head off the combination of all these measures. A good place to start would be for the U.S. Senate follow the example of the House by passing the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act. The City of Denver is reversing its previous stance against the use of police drones. The city is now buying drones to explore the effectiveness of replacing many police calls with remote aerial responses. A Denver police spokesman said that on many calls the police department will send drones first, officers second. When operators of drones see that a call was a false alarm, or that a traffic issue has been resolved, the police department will be free to devote scarce resources to more urgent priorities.

Nearby Arapahoe County already has a fleet of 20 such drones operated by 14 pilots. Arapahoe has successfully used drones to follow suspects fleeing a crime, provide live-streamed video and mapping of a tense situation before law enforcement arrives, and to look for missing people. In Loveland, Colorado, a drone was used to deliver a defibrillator to a patient before paramedics were able to get to the scene. The use of drones by local law enforcement as supplements to patrol officers is likely to grow. And why not? It makes sense for a drone to scout out a traffic accident or a crime scene for police. But as law enforcement builds more robust fleets of drones, they could be used not just to assess the seriousness of a 911 call, but to provide the basis for around-the-clock surveillance. Modern drones can deliver intimate surveillance that is more invasive than traditional searches. They can be packed with cell-simulator devices to extract location and other data from cellphones in a given area. They can loiter over a home or peek in someone’s window. They can see in the dark. They can track people and their activities through walls by their heat signatures. Two or more cameras combined can work in stereo to create 3D maps inside homes. Sensor fusion between high definition, fully maneuverable cameras can put all these together to essentially give police an inside look at a target’s life. Drones with such high-tech surveillance packages can be had on the market for around $6,000. As with so many other forms of surveillance, the modest use of this technology sounds sensible, until one considers how many other ways they can be used. Local leaders at the very least need to enact policies that put guardrails on these practices before we learn, the hard way, how drones and the data they generate can be misused. The House of Representatives on Thursday passed the CBDC Anti-Surveillance State Act, 216-192, a measure sponsored by House Majority Whip Tom Emmer (R-MN) that would prohibit the Federal Reserve from issuing a central bank digital currency (CBDC) that would give the federal government the ability to monitor and control individual Americans’ spending habits.

“A digital dollar could give the FBI and other federal agencies instant, warrantless access to every transaction of any size made between Americans,” said Bob Goodlatte, former congressman and PPSA Senior Policy Advisor. “This would be an alarming and unacceptable invasion of our Fourth Amendment right to privacy. The CBDC Anti-Surveillance State Act takes a critical step to prevent this from happening. We applaud Rep. Emmer for his leadership in protecting Americans against pervasive government surveillance of our financial data.” Perhaps next the House will consider measures to rein in financial surveillance by the U.S. Treasury and the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN). Passage by the House of the CBDC Anti-Surveillance State Act is an encouraging sign that more Members and their constituents are learning about the government’s financial surveillance and are ready to push back. Suspect: “We Have to Follow the Law. Why Don’t They?" Facial recognition software is useful but fallible. It often leads to wrongful arrests, especially given the software’s tendency to produce false positives for people of color.

We reported in 2023 on the case of Randall Reid, a Black man in Georgia, arrested and held for a week by police for allegedly stealing $10,000 of Chanel and Louis Vuitton handbags in Louisiana. Reid was traveling to a Thanksgiving dinner near Atlanta with his mother when he was arrested. He was three states and seven hours away from the scene of this crime in a state in which he had never set foot. Then there is the case of Portia Woodruff, a 32-year-old Black woman, who was arrested in her driveway for a recent carjacking and robbery. She was eight months pregnant at the time, far from the profile of the carjacker. She suffered great emotional distress and suffered spasms and contractions while in jail. Some jurisdictions have reacted to the spotty nature of facial recognition by requiring every purported “match” to be evaluated by a large team to reduce human bias. Other jurisdictions, from Boston to Austin and San Francisco, responded to the technology’s flaws by banning the use of this technology altogether. The Washington Post’s Douglas MacMillan reports that officers of the Austin Police Department have developed a neat workaround for the ban. Austin police asked law enforcement in the nearby town of Leander to conduct face searches for them at least 13 times since Austin enacted its ban. Tyrell Johnson, a 20-year-old man who is a suspect in a robbery case due to a facial recognition workaround by Austin police told MacMillan, “We have to follow the law. Why don’t they?” Other jurisdictions are accused of working around bans by posting “be on the lookout” flyers in other jurisdictions, which critics say is meant to be picked up and run through facial recognition systems by other police departments or law enforcement agencies. MacMillian’s interviews with defense lawyers, prosecutors, and judges revealed the core problem with the use of this technology – employing facial recognition to generate leads but not evidence. They told him that prosecutors are not required in most jurisdictions to inform criminal defendants they were identified using an algorithm. This highlights the larger problem with high-tech surveillance in all its forms: improperly accessed data, reviewed without a warrant, can allow investigators to work backwards to incriminate a suspect. Many criminal defendants never discover the original “evidence” that led to their prosecution, and thus can never challenge the basis for their case. This “backdoor search loophole” is the greater risk, whether one is dealing with databases of mass internet communications or facial recognition. Thanks to this loophole, Americans can be accused of crimes but left in the dark about how the cases against them were started. Now that the House has passed the Fourth Amendment Is Not for Sale Act, senators would do well to review new concessions from the intelligence community on how it treats Americans’ purchased data. This is progress, but it points to how much more needs to be done to protect privacy.

Avril Haines, Director of National Intelligence (DNI), released a “Policy Framework for Commercially Available Information,” or CAI. In plain English, CAI is all the digital data scraped from our apps and sold to federal agencies, ranging from the FBI to the IRS, Department of Homeland Security, and Department of Defense. From purchased digital data, federal agents can instantly access almost every detail of our personal lives, from our relationships to our location histories, to data about our health, financial stability, religious practices, and politics. Federal purchases of Americans’ data don’t merely violate Americans’ privacy, they kick down any semblance of it. There are signs that the intelligence community itself is coming to realize just how extreme its practices are. Last summer, Director Haines released an unusually frank report from an internal panel about the dangers of CAI. We wrote at the time: “Unlike most government documents, this report is remarkably self-aware and willing to explore the dangers” of data purchases. The panel admitted that this data can be used to “facilitate blackmail, stalking, harassment, and public shaming.” Director Haines’ new policy orders all 18 intelligence agencies to devise safeguards “tailored to the sensitivity of the information” and produce an annual report on how each agency uses such data. The policy also requires agencies:

Details for how each of the intelligence agencies will fulfill these aspirations – and actually handle “sensitive CAI” – is left up to them. Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR) acknowledged that this new policy marks “an important step forward in starting to bring the intelligence community under a set of principles and polices, and in documenting all the various programs so that they can be overseen.” Journalist and author Byron Tau told Reason that the new policy is a notable change in the government’s stance. Earlier, “government lawyers were saying basically it’s anonymized, so no privacy problem here.” Critics were quick to point out that any of this data could be deanonymized with a few keystrokes. Now, Tau says, the new policy is “sort of a recognition that this data is actually sensitive, which is a bit of change.” Tau has it right – this is a bit of a change, but one with potentially big consequences. One of those consequences is that the public and Congress will have metrics that are at least suggestive of what data the intelligence community is purchasing and how it uses it. In the meantime, Sen. Wyden says, the framework of the new policy has an “absence of clear rules about what commercially available information can and cannot be purchased by the intelligence community.” Sen. Wyden adds that this absence “reinforces the need for Congress to pass legislation protecting the rights of Americans.” In other words, the Senate must pass the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, which would subject purchased data to the same standard as any other personal information – a probable cause warrant. That alone would clarify all the rules of the intelligence community. The federal government’s hunger for financial surveillance is boundless. A central bank digital currency (CBDC) would completely satisfy it. Under a CBDC, all transactions would be recorded, giving federal agencies the means to review any Americans’ income and expenditures at a glance. Financial privacy would not be compromised: it would be dead.

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell says this country is “nowhere near” establishing a digital currency. To be sure, such an undertaking would take years. But Nigeria, Jamaica, and the Bahamas already have digital currencies. China is well along in a pilot program for a digital yuan. The U.S. government is actively exploring this as an option. It is not too early to consider the consequences of a digital dollar. Such a digital currency would create a presumably unbreakable code, or “blocks” linked together by cryptographic algorithms, to connect computers to create a digital ledger to record transactions. Some risks of a CBDC are obvious – from the breaking of “unbreakable” codes by criminals and hostile foreign governments, to the temptation for Washington, D.C., to expand the currency with a few clicks, making it all the easier to inflate the currency. House Majority Whip, Rep. Tom Emmer (R-MN), is especially concerned about the privacy implications of a digital currency. “If not designed to be open, permissionless, and private – emulating cash – a government-issued CBDC is nothing more than a CCP-style (Chinese Communist Party) surveillance tool that would be used to undermine the American way of life,” Rep. Emmer said. He is expected to soon reintroduce a bill that would require any central bank digital currency to require authorizing legislation from Congress before it could be enacted. Emmer’s stand is prescient, not premature. From the new requirement for “beneficial ownership” forms by small businesses, to the revelation from House hearings of warrantless, dragnet surveillance through credit card and ATM transactions, the federal government is inventing new ways to track our every financial move. Rep. Emmer is right to head this one off at the pass. PPSA endorses this bill and urges Emmer’s colleagues to pass it into law. A new fiat currency should have the permission of Congress and the American people. The Federal Government’s “Beneficial Ownership” Snoop Millions of small business owners are about to be hit with a nasty surprise. The Corporate Transparency Act, which passed Congress as part of the must-pass National Defense Authorization Act of 2021, goes into effect this year. Advertised as a way to combat money laundering, this new law now requires small businesses to report their “beneficial owners” to the U.S. Department of Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN).

This reporting requirement falls on any small business with fewer than 20 employees to reveal its “beneficial owner.” In plain English, this means a small business must give the government the name of anyone who controls or has a 25 percent or greater interest in that business. By Jan. 1, 2025, small businesses must submit the full legal name, date of birth, current residential or business address, and a unique identifier from a government ID of all its beneficial owners. There are significant privacy risks at stake in this seemingly innocuous law, beginning with the widespread access multiple federal agencies will have to this new database. This law, which covers 32 million existing companies and will suck in an additional 5 million new companies every year, threatens anyone who makes a mistake or files an incomplete submission with up to $10,000 in fines and up to two years in prison. “The CTA will potentially make a felon out of any unsuspecting person who is simply trying to make a living in his or her own lawful business or who is trying to start one and makes a simple mistake for violations,” says the National Small Business Association (NSBA). The “beneficial ownership” provision is one more way for the federal government to break down the walls of financial privacy in its quest to comprehensively track Americans’ finances. Consider another big bill, the recent Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021, which requires $10,000 or more in cryptocurrency transactions to be reported to the government within 15 days. Incorrect or missing information may result in a $25,000 fine or five years in prison. In addition, the CATO Institute reports that new regulations under consideration would hold financial advisors accountable to “elements of the Bank Secrecy Act, which currently compels banks to turn over certain financial data to the feds.” It is likely that your financial advisor will soon be required to snitch on you. This undermines the whole concept of a fiduciary, someone who is by law supposed to be loyal to your interests. All of these measures are justified by the quest to track the money networks of criminals, terrorists, and drug dealers. But the data these authorities generate will be available, without a warrant, to the IRS, the FBI, the ATF, the Department of Homeland Security, and just about any agency that wants to investigate you for your personal activities or statements that some official deems suspicious. The CTA’s “beneficial ownership” provision represents a new assertion by the federal government over small business. Since before the Constitution, the regulation of small business has been under the purview of the states. Now Washington is assembling a database with which it can heap new regulations on small business regardless of state policies. The NSBA, which is challenging this law in court, estimates that complexities in business ownership will require companies to spend an average of $8,000 a year to comply with this law. NSBA’s lawsuit is moving forward with a named plaintiff, Huntsville business owner Isaac Winkles, in a federal lawsuit. NSBA and Winkles won summary judgment from Judge Liles Burke of the U.S. District Court of the Northern District of Alabama, who held the beneficial owner requirement to be unconstitutional because it exceeds the enumerated powers of Congress. While the government appeals its case to the Eleventh Circuit, FinCEN maintains that it will only exclude small businesses from this requirement if they were members of NSBA on or before March 1. These encroachments are steady and their champions on the Hill are growing bolder in financial surveillance. The good news is that privacy activists have just acquired 32 million new allies. Well, that didn’t take long.

A little more than three weeks ago Congress reauthorized FISA Section 702, a surveillance program enacted to authorize foreign surveillance but which is often used by the FBI to snoop on Americans’ communications caught up in the NSA’s global data trawl. Central to that debate was whether 702 should be made to conform to the Fourth Amendment’s bar against unreasonable searches. The House and Senate fiercely debated late into the night over whether to reauthorize this flawed program. Supporters said it is vital to national security. Critics said that is no excuse for the FBI using Section 702 to surveil large numbers of Americans in recent years, including sitting Members of the House and Senate, journalists, politicians, a state judge, and 19,000 donors to a Congressional campaign. In the House that debate culminated in a 212 to 212 tie vote. That’s how close advocates of privacy and freedom for law-abiding citizens from warrantless government surveillance came to victory. The intelligence establishment and its champions on Capitol Hill won many votes with promises. They included in their bill a codification of a list of new internal FBI procedures that they promised would curb any abuses of Americans’ privacy. FBI Director Christopher Wray promised that agents would be “good stewards” who would protect the homeland “while safeguarding civil rights and liberties.” On April 19, the Senate finalized the reauthorization of Section 702 and sent it to President Biden to be signed into law. On April 20, FBI deputy director Paul Abbate emailed Bureau employees, stating: “To continue to demonstrate why tools like this [Section 702] are essential, we need to use them, while also holding ourselves accountable for doing so properly and in compliance with legal requirements.” He added, “I urge everyone to continue to look for ways to appropriately use US person queries to advance the mission …” Wired, which obtained a copy of the memo, quoted Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-CA), who said that Deputy Director Abbate’s email directly contradicted earlier assertions from the FBI made during the debate over Section 702’s reauthorization. “The deputy director’s email seems to show that the FBI is actively pushing for more surveillance of Americans, not out of necessity but as a default,” Rep. Lofgren said. The FBI reports it has drawn down the number of such U.S. person queries from about 3 million in 2021 to 57,094 in 2023. As Wired notes, however, the FBI methodology counts multiple accessing of Americans’ personal identifier, such as phone numbers, as just a single search. As Wired reports, the FBI’s proud assertion that its compliance rate of 98 percent with its more stringent rules would still leave it with more than 1,000 violations of its own policies. With the deputy director arrogantly pushing the Bureau to make greater use of Section 702 for the warrantless surveillance of Americans, we can only wonder what the numbers of U.S. person searches will be in the next few years. Whatever happens, the more than 150 civil liberties organizations, including PPSA, will be back when Section 702 is next up for reauthorization in less than two years. The Constitution’s protections of the people cannot be ignored. A recent House hearing on the protection of journalistic sources veered into startling territory.

As expected, celebrated investigative journalist Catherine Herridge spoke movingly about her facing potential fines of up to $800 a day and a possible lengthy jail sentence as she faces a contempt charge for refusing to reveal a source in court. Herridge said one of her children asked, “if I would go to jail, if we would lose our house, and if we would lose our family savings to protect my reporting source.” Herridge later said that CBS News’ seizure of her journalistic notes after laying her off felt like a form of “journalistic rape.” Witnesses and most members of the House Judiciary subcommittee on the Constitution and Limited Government agreed that the Senate needs to act on the recent passage of the bipartisan Protect Reporters from Exploitative State Spying (PRESS) Act. This bill would prevent federal prosecutors from forcing journalists to burn their sources, as well to bar officials from surveilling phone and email providers to find out who is talking to journalists. Sharyl Attkisson, like Herridge a former CBS News investigative reporter, brought a dose of reality to the proceeding, noting that passing the PRESS Act is just the start of what is needed to protect a free press. “Our intelligence agencies have been working hand in hand with the telecommunications firms for decades, with billions of dollars in dark contracts and secretive arrangements,” Attkisson said. “They don’t need to ask the telecommunications firms for permission to access journalists’ records, or those of Congress or regular citizens.” Attkisson recounted that 11 years ago CBS News officially announced that Attkisson’s work computer had been targeted by an unauthorized intrusion. “Subsequent forensics unearthed government-controlled IP addresses used in the intrusions, and proved that not only did the guilty parties monitor my work in real time, they also accessed my Fast and Furious files, got into the larger CBS system, planted classified documents deep in my operating system, and were able to listen in on conversations by activating Skype audio,” Attkisson said. If true, why would the federal government plant classified documents in the operating system of a news organization unless it planned to frame journalists for a crime? Attkisson went to court, but a journalist – or any citizen – has a high hill to climb to pursue an action against the federal government. Attkisson spoke of the many challenges in pursuing a lawsuit against the Department of Justice. “I’ve learned that wrongdoers in the federal government have their own shield laws that protect them from accountability,” Attkisson said. “Government officials have broad immunity from lawsuits like mine under a law that I don’t believe was intended to protect criminal acts and wrongdoing but has been twisted into that very purpose. “The forensic proof and admission of the government’s involvement isn’t enough,” she said. “The courts require the person who was spied on to somehow produce all the evidence of who did what – prior to getting discovery. But discovery is needed to get more evidence. It’s a vicious loop that ensures many plaintiffs can’t progress their case even with solid proof of the offense.” Worse, Attkisson testified that a journalist “who was spied on has to get permission from the government agencies involved in order to question the guilty agents or those with information, or to access documents. It’s like telling an assault victim that he has to somehow get the attacker’s permission in order to obtain evidence. Obviously, the attacker simply says no. So does the government.” This hearing demonstrated how important Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable searches and seizures are to the First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of the press. If Attkisson’s claims are true, the government explicitly violated a number of laws, not the least of which is mishandling classified documents and various cybercrimes. And it relies on specious immunities and privileges to avoid any accountability for its apparent crimes. Two proposed laws are a good way to start reining in such government misconduct. The first is the PRESS Act, which would protect journalists’ sources against being pressured by prosecutors in federal court to reveal their sources. The second proposed law is the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, which passed the House last week. This bill would require the government to get a warrant before it can inspect our personal, digital information sold by data brokers. And, of course, these and other laws limiting government misconduct need genuine remedies and consequences for misconduct, not the mirage of remedies enfeebled by improper immunities. Five Maine lobstermen are suing Maine’s Department of Marine Resources after the agency issued regulations requiring electronic tracking of vessels fishing in federal waters. The plaintiffs allege such tracking violates privacy rights, due process, and equal protection under the Constitution. It’s a red-hot, lobster pot controversy with significant implications on the ever-evolving body of law surrounding geolocation tracking and surveillance.

Maine adopted the tracking regulation in December to comply with a requirement issued by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, whose overarching policy objective here is to help protect the North Atlantic right whale. This is certainly a noble objective, but it brings with it troubling implications. Maine Department of Marine Resources Commissioner Patrick Keliher makes the argument that because lobstermen work in a “closely regulated industry,” they have “a greatly reduced expectation of privacy.” It’s a common refrain for those seeking to impose new surveillance measures. But as attorney John Vecchione of the New Civil Liberties Alliance once said, “the expansion of closely regulated-industry theory is a huge, huge danger to liberties for everybody.” Indeed, as society, the economy, and ensuing regulations grow, simply having to get a license could subject any business to warrantless inspections. Such an argument could be used to attach trackers to realtors as they move around from house to house, salespersons, contractors, or any other group of mobile professionals. The U.S. District Court for the District of Maine, where the case was filed, might take a page from the Fifth Circuit, which in 2023 struck down a U.S. Department of Commerce requirement that would have forced charter boat owners to install, at their own expense, a “vessel monitoring system” that would continuously transmit their boats’ location, regardless of whether it was being used for commercial or personal purposes. In that case, the court found that it “borders on incredible” that the government claimed it failed to notice personal privacy concerns in public comments to its rule. The court, further, found that discovery of prime fishing spots in the Gulf would constitute a hardship for many charter operators. Similarly, attorneys for the suing lobstermen argue that they “jealously guard the whereabouts and the techniques they use to place their traps. This is directly correlated to their ability to make a living.” It’s not just fishing locations that are at risk, however. The U.S. Supreme Court has repeatedly held that warrantless GPS tracking constitutes an unlawful search. Tracking someone’s movements, it needn’t be emphasized, can reveal quite a lot about their personal and private lives. As the Maine federal court considers these issues, we side unequivocally with the lobstermen. Simply put, there must be a way to balance the privacy interests of fishermen and the policy objective of protecting marine life. Top-down surveillance mandates seem a poor fit. Forbes reports that federal authorities were granted a court order to require Google to hand over the names, addresses, phone numbers, and user activities of internet surfers who were among the more than 30,000 viewers of a post. The government also obtained access to the IP addresses of people who weren’t logged onto the targeted account but did view its video.

The post in question is suspected of being used to promote the sale of bitcoin for cash, which would be a violation of money-laundering rules. The government likely had good reason to investigate that post. But did it have to track everyone who came into contact with it? This is a prime example of the government’s street-sweeper shotgun approach to surveillance. We saw this when law enforcement in Virginia tracked the location histories of everyone in the vicinity of a robbery. A state judge later found that search meant that everyone in the area, from restaurant patrons to residents of a retirement home, had “effectively been tailed.” We saw the government shotgun approach when the FBI secured the records of everyone in the Washington, D.C., area who used their debit or credit cards to make Bank of America ATM withdrawals between Jan. 5 and Jan. 7, 2021. We also saw it when the FBI, searching for possible foreign influence in a congressional campaign, used FISA Section 702 data – meant to surveil foreign threats on foreign soil – to pull the data of 19,000 political donors. Surfing the web is not inherently suspicious. What we watch online is highly personal, potentially revealing all manner of social, romantic, political, and religious beliefs and activities. The Founders had such dragnet-style searches precisely in mind when they crafted the Fourth Amendment. Simply watching a publicly posted video is not by itself probable cause for search. It should not compromise one’s Fourth Amendment rights. Byron Tau – journalist and author of Means of Control, How the Hidden Alliance of Tech and Government Is Creating a New American Surveillance State – discusses the details of his investigative reporting with Liza Goitein, senior director of the Brennan Center for Justice's Liberty & National Security Program, and Gene Schaerr, general counsel of the Project for Privacy and Surveillance Accountability.

Byron explains what he has learned about the shadowy world of government surveillance, including how federal agencies purchase Americans’ most personal and sensitive information from shadowy data brokers. He then asks Liza and Gene about reform proposals now before Congress in the FISA Section 702 debate, and how they would rein in these practices. Just as the government hates encryption, so too does it hate encryption’s physical analogue in the form of safety deposit boxes.

The mere existence of US Private Vaults – a company in Beverly Hills that could not reveal customers’ names because it did not collect them and could not open the vaults it provided because it did not keep duplicate keys – was prima facie evidence to the FBI of wrongdoing. Seeking to expose what it believed would be a nest of drug dealer cash, the FBI persuaded a magistrate to allow agents to open these vaults with the express purpose of checking the identities of account holders on sheets taped to the inside of the vault’s safety deposit boxes. FBI agents took this warrant as an excuse to seize assets over $5,000 – though the owners were charged with no crime. In 2021, Reason documented in stills taken from surveillance footage how agents rampaged through the vaults and boxes in a frenzy, ripping open a heavy-duty envelope full of gold coins kept by an 80-year-old woman for her retirement savings. Coins fell to the floor, which the FBI cannot account for now. Some $2,000 in cash seemingly “disappeared.” The woman and other victims, with the help of the Institute for Justice, mounted a class-action lawsuit against the FBI. While US Private Vaults later pled guilty to money laundering charges, these plaintiffs had a host of mundane reasons for turning to its services. Reasons varied from distrust of the stability of banks during the Covid era, to transferring assets from a bank in a wildfire zone, to finding that safety deposit boxes at other institutions had long waiting lists. The Ninth Circuit unanimously reversed a lower court verdict and rebuked the FBI for a lawless search. Judge Milan Smith Jr. said the government had opened the door to the “limitless searches of an individual’s personal belongings” reminiscent of the agents of the British crown in ransacking colonial America. The Ninth’s strong stand for the Fourth Amendment is good news. But, as we have seen in governments’ war on encryption, there is a mindset shared by many in law enforcement that something private is inherently suspicious and worthy of warrantless examination. The reform coalition on Capitol Hill remains determined to add strong amendments to Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). But will they get the chance before an April 19th deadline for FISA Section 702’s reauthorization?

There are several possible scenarios as this deadline closes. One of them might be a vote on the newly introduced “Reforming Intelligence and Securing America” (RISA) Act. This bill is a good-faith effort to represent the narrow band of changes that the pro-reform House Judiciary Committee and the status quo-minded House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence could agree upon. But is it enough? RISA is deeply lacking because it leaves out two key reforms.

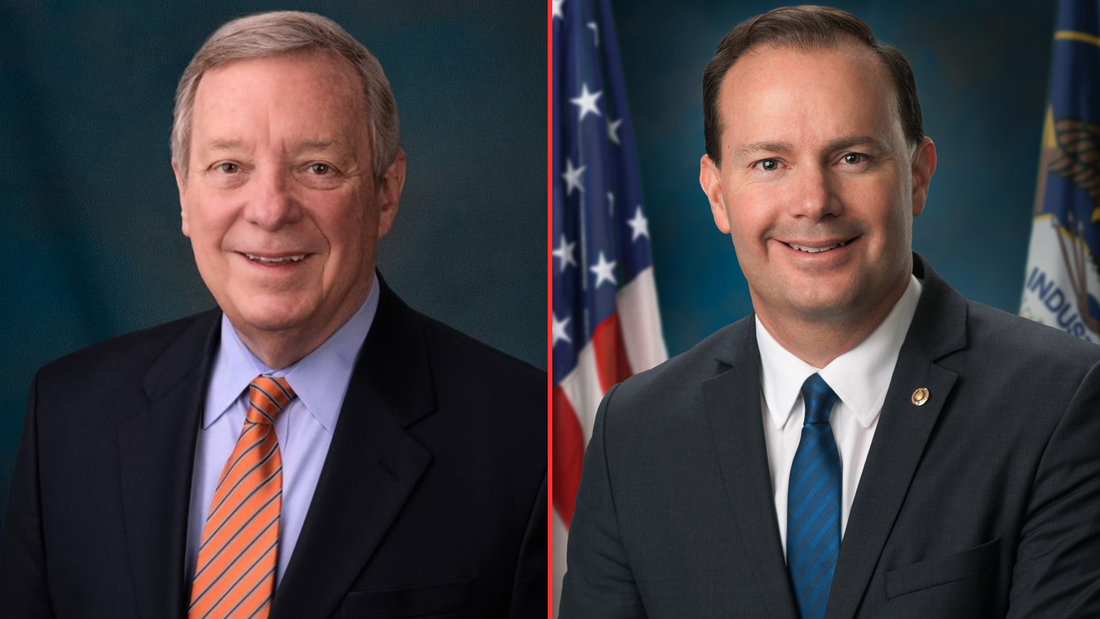

The bill does include a role for amici curiae, specialists in civil liberties who would act as advisors to the secret FISA court. RISA, however, would limit the issues these advisors could address, well short of the intent of the Senate when it voted 77-19 in 2020 to approve the robust amici provisions of the Lee-Leahy amendment. For all these reasons, reformers should see RISA as a floor, not as a ceiling, as the Section 702 showdown approaches. The best solution to the current impasse is to stop denying Members of Congress the opportunity for a straight up-or-down vote on reform amendments. The reauthorization of FISA Section 702, which allows federal agencies to conduct international surveillance for national security purposes, has languished in Congress like an old Spanish galleon caught in the doldrums. This happened after opponents of reform pulled Section 702 reauthorization from the House floor rather than risk losing votes on popular measures, such as requiring government agencies to obtain warrants before surveilling Americans’ communications.

But the winds are no longer becalmed. They are picking up – and coming from the direction of reform. Sen. Dick Durbin (D-IL), Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, and fellow committee member Sen. Mike Lee (R-UT), today introduced the Security and Freedom Enhancement (SAFE) Act. This bill requires the government to obtain warrants or court orders before federal agencies can access Americans’ personal information, whether from Section 702-authorized programs or purchased from data brokers. Enacted by Congress to enable surveillance of foreign targets in foreign lands, Section 702 is used by the FBI and other federal agencies to justify domestic spying. According to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) Court, under Section 702 government “batch” searches have included a sitting U.S. Congressman, a U.S. Senator, journalists, political commentators, a state senator, and a state judge who reported civil right violations by a local police chief to the FBI. It has even been used by government agents to stalk online romantic prospects. Millions of Americans in recent years have had their communications compromised by programs under Section 702. The reforms of the SAFE Act promise to reverse this trend, protecting Americans’ privacy and constitutional rights from the government. The SAFE Act requires:

Durbin-Lee is a pragmatic bill. It lifts warrants and other requirements in emergency circumstances. The SAFE Act allows the government to obtain consent for surveillance if the subject of the search is a potential victim or target of a foreign plot. It allows queries designed to identify targets of cyberattacks, where the only content accessed and reviewed is malicious software or cybersecurity threat signatures. The SAFE Act is a good-faith effort to strike a balance between national security and Americans’ privacy. It should break the current stalemate, renewing the push for debate and votes on amendments to the reauthorization of Section 702. While Congress debates adding reforms to FISA Section 702 that would curtail the sale of Americans’ private, sensitive digital information to federal agencies, the Federal Trade Commission is already cracking down on companies that sell data, including their sales of “location data to government contractors for national security purposes.”

The FTC’s words follow serious action. In January, the FTC announced proposed settlements with two data aggregators, X-Mode Social and InMarket, for collecting consumers’ precise location data scraped from mobile apps. X-Mode, which can assimilate 10 billion location data points and link them to timestamps and unique persistent identifiers, was targeted by the FTC for selling location data to private government contractors without consumers’ consent. In February, the FTC announced a proposed settlement with Avast, a security software company, that sold “consumers’ granular and re-identifiable browsing information” embedded in Avast’s antivirus software and browsing extensions. What is the legal basis for the FTC’s action? The agency seems to be relying on Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act, which grants the FTC power to investigate and prevent deceptive trade practices. In the case of X-Mode, the FTC’s proposed complaint highlight’s X-Mode’s statement that their location data would be used solely for “ad personalization and location-based analytics.” The FTC alleges X-Mode failed to inform consumers that X-Mode “also sold their location data to government contractors for national security purposes.” The FTC’s evolving doctrine seems even more expansive, weighing the stated purpose of data collection and handling against its actual use. In a recent blog, the FTC declares: “Helping people prepare their taxes does not mean tax preparation services can use a person’s information to advertise, sell, or promote products or services. Similarly, offering people a flashlight app does not mean app developers can collect, use, store, and share people’s precise geolocation information. The law and the FTC have long recognized that a need to handle a person’s information to provide them a requested product or service does not mean that companies are free to collect, keep, use, or share that’s person’s information for any other purpose – like marketing, profiling, or background screening.” What is at stake for consumers? “Browsing and location data paint an intimate picture of a person’s life, including their religious affiliations, health and medical conditions, financial status, and sexual orientation.” If these cases go to court, the tech industry will argue that consumers don’t sign away rights to their private information when they sign up for tax preparation – but we all do that routinely when we accept the terms and conditions of our apps and favorite social media platforms. The FTC’s logic points to the common understanding that our data is collected for the purpose of selling us an ad, not handing over our private information to the FBI, IRS, and other federal agencies. The FTC is edging into the arena of the Fourth Amendment Is Not for Sale Act, which targets government purchases and warrantless inspection of Americans’ personal data. The FTC’s complaints are, for the moment, based on legal theory untested by courts. If Congress attaches similar reforms to the reauthorization of FISA Section 702, it would be a clear and hard to reverse protection of Americans’ privacy and constitutional rights. Ken Blackwell, former ambassador and mayor of Cincinnati, has a conservative resume second to none. He is now a senior fellow of the Family Research Council and chairman of the Conservative Action Project, which organizes elected conservative leaders to act in unison on common goals. So when Blackwell writes an open letter in Breitbart to Speaker Mike Johnson warning him not to try to reauthorize FISA Section 702 in a spending bill – which would terminate all debate about reforms to this surveillance authority – you can be sure that Blackwell was heard.

“The number of FISA searches has skyrocketed with literally hundreds of thousands of warrantless searches per year – many of which involve Americans,” Blackwell wrote. “Even one abuse of a citizen’s constitutional rights must not be tolerated. When that number climbs into the thousands, Congress must step in.” What makes Blackwell’s appeal to Speaker Johnson unique is he went beyond including the reform efforts from conservative stalwarts such as House Judiciary Committee Chairman Jim Jordan and Rep. Andy Biggs of the Freedom Caucus. Blackwell also cited the support from the committee’s Ranking Member, Rep. Jerry Nadler, and Rep. Pramila Jayapal, who heads the House Progressive Caucus. Blackwell wrote: “Liberal groups like the ACLU support reforming FISA, joining forces with conservatives civil rights groups. This reflects a consensus almost unseen on so many other important issues of our day. Speaker Johnson needs to take note of that as he faces pressure from some in the intelligence community and their overseers in Congress, who are calling for reauthorizing this controversial law without major reforms and putting that reauthorization in one of the spending bills that will work its way through Congress this month.” That is sound advice for all Congressional leaders on Section 702, whichever side of the aisle they are on. In December, members of this left-right coalition joined together to pass reform measures out of the House Judiciary Committee by an overwhelming margin of 35 to 2. This reform coalition is wide-ranging, its commitment is deep, and it is not going to allow a legislative maneuver to deny Members their right to a debate. |

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed