PPSA Asks Supreme Court to Hear X Corp.’s Constitutional Case Against Surveillance Gag Orders7/10/2024

PPSA announced today the filing of an amicus brief asking the U.S. Supreme Court to take up a case in which X Corp., formerly Twitter, objects to surveillance and gag orders that violate the First Amendment and pose a threat to the Fourth and Sixth Amendments as well.

When many consumers think of their digital privacy, they think first of what’s on their computers and shared with others by text or email. But the complex, self-regulating network that is the internet is not so simple. Our online searches, texts, images, and emails – including sensitive, personal information about health, mental health, romances, and finances – are backed up on the “cloud,” including data centers like X Corp.’s that distribute storage and computing capacity. Therein lies the greatest vulnerability for government snooping. The growth of data centers is prolific, rising from 2,600 to 5,300 such centers in 2024. And with it, so have government demands for our data. When federal agencies – often without a warrant – seek to access Americans’ personal data, more often than not they go to the companies that store the data in places like these data centers. For years, this power involved large social media and telecom companies. The power of the government to extract data, already robust, increased exponentially with the reauthorization of FISA Section 702 in April, which included what many call the “Make Everyone a Spy Act.” This provision defines an electronic communication service provider as virtually any company that merely has access to equipment, like Wi-Fi and routers, that is used to transmit or store electronic communications. On top of that, the government then slaps the data center or service provider with a Non-Disclosure Order (NDO), a gag order that prevents the company from informing customers that their private information has been reviewed. One such company – X Corp. – has been pressing a constitutional challenge against this practice regarding a government demand for former President Trump’s account data. PPSA has joined in an amicus brief supporting X’s bid for certiorari, asking the Court to consider the constitutional objections to government conscription of companies that host consumers’ data as adjunct spies, while restraining their ability to speak out on this conscription. In the case of X, the government has seized the company’s records on customer communications and then slapped the company with an NDO to force it to shut up about it. The government claims this secrecy is needed to protect the investigation, even though the government itself has already publicized the details of its investigation. Whatever you think of Donald Trump, this is an Orwellian practice. PPSA’s amicus brief informed the Court that the gag order “makes a mockery of the First Amendment’s longstanding precedent governing prior restraints. And it will only become more frequent as third-party cloud storage becomes increasingly common for everything from business records to personal files to communications …” The brief informs the Court: “NDOs can be used to undermine other constitutionally protected rights” beyond the First Amendment. These rights include the short-circuiting of Fourth Amendment rights against warrantless searches and Sixth Amendment rights to a public trial in which a defendant can know the evidence against him. Partial solutions to these short-comings are winding their way through the legislative process. Sen. Mark Warner, Chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, introduced legislation to narrow the scope of businesses covered by the new, almost-universal dragooning of businesses large and small as government spies – though House Intelligence Chairman Mike Turner is opposing that reasonable provision. Last year, the House passed the NDO Fairness Act, which requires judicial review and limited disclosures for these restraints on speech and privacy. As partial solutions wend their way through Congress, this case presents a number of well-defined concerns best defined by the Supreme Court. PPSA has fired off a succession of Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to leading federal law enforcement and intelligence agencies. These FOIAs seek critical details about the government’s purchasing of Americans’ most sensitive and personal data scraped from apps and sold by data brokers.

PPSA’s FOIA requests were sent to the Department of Justice and the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security, the CIA, the Defense Intelligence Agency, the National Security Agency, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, asking these agencies to reveal the broad outlines of how they collect highly private information of Americans. These digital traces purchased by the government reveal Americans’ familial, romantic, professional, religious, and political associations. This practice is often called the “data broker loophole” because it allows the government to bypass the usual judicial oversight and Fourth Amendment warrant requirement for obtaining personal information. “Every American should be deeply concerned about the extent to which U.S. law enforcement and intelligence agencies are collecting the details of Americans’ personal lives,” said Gene Schaerr, PPSA general counsel. “This collection happens without individuals’ knowledge, without probable cause, and without significant judicial oversight. The information collected is often detailed, extensive, and easily compiled, posing an immense threat to the personal privacy of every citizen.” To shed light on these practices, PPSA is requesting these agencies produce records concerning:

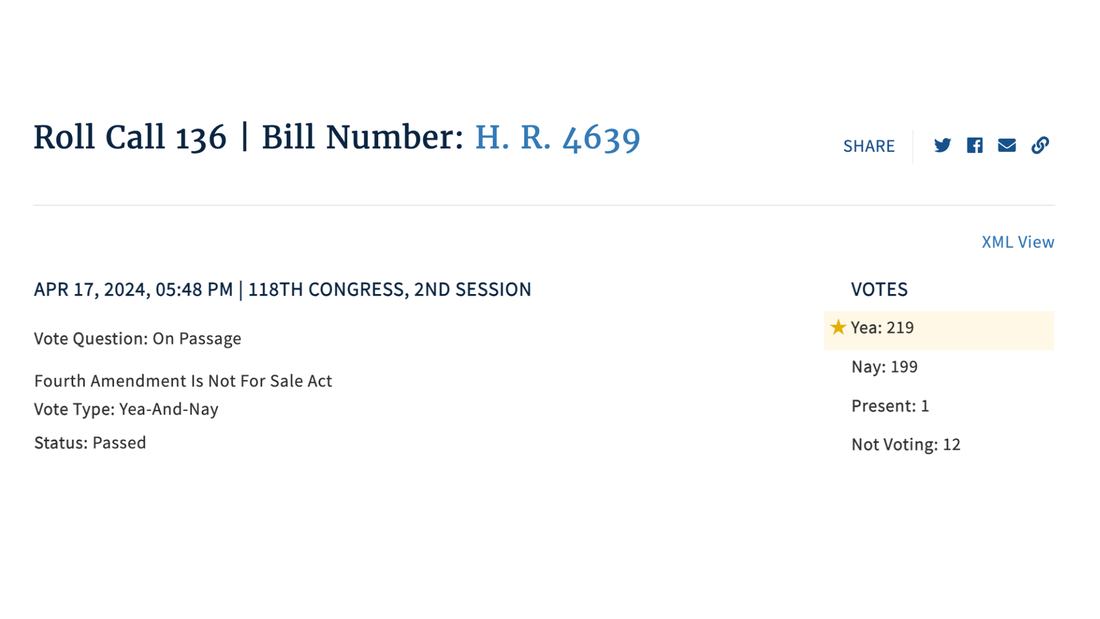

Shortly after the House passed the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, which would require the government to obtain probable cause warrants before collecting Americans’ personal data, Avril Haines, Director of National Intelligence, ordered all 18 intelligence agencies to devise safeguards “tailored to the sensitivity of the information.” She also directed them to produce an annual report on how each agency uses such data. PPSA believes that revealing, in broad categories, the size, scope, sources, and types of data collected by agencies, would be a good first step in Director Haines’ effort to provide more transparency on data purchases. The recent passage of the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act by the House marks a bold and momentous step toward protecting Americans' privacy from unwarranted government intrusion. This legislation mandates that federal law enforcement and intelligence agencies, such as the FBI and CIA, must obtain a probable cause warrant before purchasing Americans’ personal data from brokers. This requirement closes a loophole that allows agencies to compromise the privacy of Americans and bypass constitutional safeguards.

While this act primarily targets law enforcement and intelligence agencies, it is crucial to extend these protections to all federal agencies. Non-law enforcement entities like the Treasury Department, IRS, and Department of Health and Human Services are equally involved in the purchase of Americans' personal data. The growing appetite among these agencies to track citizens' financial data, sensitive medical issues, and personal lives highlights the need for a comprehensive warrant requirement across the federal government. How strong is that appetite? The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), operating under the Treasury Department, exemplifies the ambitious scope of federal surveillance. Through initiatives like the Corporate Transparency Act, FinCEN now requires small businesses to disclose information about their owners. This data collection is ostensibly for combating money laundering, though it seems unlikely that the cut-outs and money launderers for cocaine dealers and human traffickers will hesitate to lie on an official form. This data collection does pose significant privacy risks by giving multiple federal agencies warrantless access to a vast database of personal information of Americans who have done nothing wrong. The potential consequences of such data collection are severe. The National Small Business Association reports that the Corporate Transparency Act could criminalize small business owners for simple mistakes in reporting, with penalties including fines and up to two years in prison. This overreach underscores the broader issue of federal agencies wielding excessive surveillance powers without adequate checks and balances. Another alarming example is the dragnet financial surveillance revealed by the House Judiciary Committee and its Select Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Federal Government. The FBI, in collaboration with major financial institutions, conducted sweeping investigations into individuals' financial transactions based on perceptions of their political leanings. This surveillance was conducted without probable cause or warrants, targeting ordinary Americans for exercising their constitutional rights. Without statutory guardrails, such surveillance could be picked up by non-law enforcement agencies like FinCEN, using purchased digital data. These examples demonstrate the appetite of all government agencies for our personal information. Allowing them to also buy our most sensitive and personal information from data brokers, which is happening now, is about an absolute violation of Americans’ privacy as one can imagine. Only listening devices in every home could be more intrusive. Such practices are reminiscent of general warrants of the colonial era, the very abuses the Fourth Amendment was designed to prevent. The indiscriminate collection and scrutiny of personal data without individualized suspicion erode the foundational principles of privacy and due process. The Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act is a powerful and necessary step to end these abuses. Congress should also consider broadening the scope to ensure all federal agencies are held to the same standard. Katie King in the Virginian-Pilot reports an in-depth account about the growing dependency of local law enforcement agencies on Flock Safety cameras, mounted on roads and intersections to catch drivers suspected of crimes. With more than 5,000 police agencies across the nation using these devices, the privacy implications are enormous.

Surveillance cameras have been in the news at lot lately, often in a positive light. Local news is consumed by murder suspects and porch pirates alike captured on video. The recently released video of a physical attack by rapper Sean “Diddy” Combs on a girlfriend several years ago has saturated media, reminding us that surveillance can protect the vulnerable. The crime-solving potential of license plate readers is huge. Flock’s software runs license plate numbers through law enforcement databases, allowing police to quickly track a stolen car, locate suspects fleeing a crime, or find a missing person. With such technologies, Silver and Amber alerts might one day become obsolete. As with facial recognition technology, however, license plate readers can produce false positives, ensnaring innocent people in the criminal justice system. King recounts the ordeal of an Ohio man who was arrested by police with drawn guns and a snarling dog. Flock’s license plate reader had falsely flagged his vehicle as having stolen tags. The good news is that Flock insists it is not even considering combining its network with facial recognition technology – reducing the possibility of both technologies flagging someone as dangerous. As with so many surveillance technologies, the greater issue in license-plate readers is not the technology itself, but how it might be used in a network. “There’s a simple principle that we’ve always had in this country, which is that the government doesn’t get to watch everybody all the time just in case somebody commits a crime – the United States is not China,” Jay Stanley, a senior analyst with the American Civil Liberties Union, told King. “But these cameras are being deployed with such density that it’s like GPS-tracking everyone.” License plate readers could, conceivably, be networked to track everywhere that everyone goes – from trips to mental health clinics, to gun stores, to houses of worship, and protests. With so many federal agencies already purchasing Americans’ sensitive data from data brokers, creating a national network of drivers’ whereabouts is just one more addition to what is already becoming a national surveillance system. With apologies to Jay Stanley, we are in serious danger of becoming China. As massive databases compile facial recognition, location data, and now driving routes, we need more than ever to head off the combination of all these measures. A good place to start would be for the U.S. Senate follow the example of the House by passing the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act. The surveillance state is hitting small businesses hard lately. If the “Make Everyone a Spy” provision weren’t enough, the Corporate Transparency Act (CTA) imposes sweeping disclosure requirements on “beneficial owners” of small businesses, with harsh punishments for mistakes on an official form.

After the National Small Business Association sued the Treasury Department, a federal court declared the CTA unconstitutional. It issued a scholarly opinion that explored the nuances of Congress’s power to regulate interstate commerce. Treasury appealed to the Eleventh Circuit. In our amicus brief, PPSA tells the Eleventh Circuit that the lower court got it right, but that there’s an easier way to resolve this case. We inform the court that the Fourth Amendment provides the “straightforward and resounding answer” that the CTA is unconstitutional. PPSA warns that the CTA’s database provisions pose an unprecedented threat to Americans’ privacy that are “even more disturbing” than the new rule’s disclosure requirements. We explain that the information collected from tens of millions of beneficial owners will be stored in what the government calls an “accurate, complete, and highly useful database” that can be searched by multiple federal agencies, no warrant required. And while the government claims this data will be used to catch tax cheats, the CTA says it will be used in conjunction with state and tribal authorities, who have no power to enforce federal tax laws. Creating such a database for warrantless inspection by the FBI, IRS, DEA, and Department of Homeland Security is obviously ripe for abuse. Our brief explains how this database could be used to identify owners of businesses with an ideological character – like political booksellers – and single out their investors for retaliation. This is not a far-fetched hypothetical. Many agencies, including the Treasury Department, have engaged in politically motivated financial investigations, documented in detail by the House Judiciary Committee. Our brief notes that the database will be so sophisticated that it should be evaluated under a U.S. Supreme Court precedent addressing high-tech surveillance, just as the Fourth Circuit did for Baltimore’s database-driven aerial surveillance program. And that precedent explains that surveillance tools can’t be used to undermine the sort of privacy that existed when the Fourth Amendment was adopted. We told the court: “This database thus has the sort of ‘depth, breadth, and comprehensive reach,’ that is simply incompatible with ‘preservation of that degree of privacy against government that existed when the Fourth Amendment was adopted.’” As pernicious as the database itself is, recent advances in technology make it even worse. With modern machine learning, seemingly innocuous personal details can be linked up in disturbing ways. For instance, researchers have known how to identify authors based on a collection of anonymous posts since 2022. PPSA points out that the government could identify authors with views it dislikes, see if they pop up in the beneficial owner database, and have multiple agencies launch pretextual investigations. Next, we address how advancing AI technology could make such surveillance even more potent, then urged the court not to “leave the public at the mercy of advancing technology,” but to preserve Founding-era levels of privacy despite the march of technology. Readers might notice a pattern of AI exacerbating existing privacy invasions, from mass facial recognition to drone surveillance to a proliferating body of databases. So far, the government has relied on the “special needs” exception. This rule allows the government to keep its own house in order, with the warrantless drug testing of schoolteachers and top-secret national security employees. But this authority is often abused, as we’ve noted previously. Our brief explains that this exception doesn’t even apply to information collected to identify crimes – which is exactly what the government claims the CTA is supposed to help with. But the struggle for constitutional rights and privacy remains multilayered. If the CTA remains struck down, the government will still be purchasing vast amounts of Americans’ personal information from shady “data brokers.” That’s why we applauded the House recently for passing the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, and urge the Senate to do so as well. Now it is up to the Eleventh Circuit to protect the American people from an overbearing government, hungry to track our every move. Now that the House has passed the Fourth Amendment Is Not for Sale Act, senators would do well to review new concessions from the intelligence community on how it treats Americans’ purchased data. This is progress, but it points to how much more needs to be done to protect privacy.

Avril Haines, Director of National Intelligence (DNI), released a “Policy Framework for Commercially Available Information,” or CAI. In plain English, CAI is all the digital data scraped from our apps and sold to federal agencies, ranging from the FBI to the IRS, Department of Homeland Security, and Department of Defense. From purchased digital data, federal agents can instantly access almost every detail of our personal lives, from our relationships to our location histories, to data about our health, financial stability, religious practices, and politics. Federal purchases of Americans’ data don’t merely violate Americans’ privacy, they kick down any semblance of it. There are signs that the intelligence community itself is coming to realize just how extreme its practices are. Last summer, Director Haines released an unusually frank report from an internal panel about the dangers of CAI. We wrote at the time: “Unlike most government documents, this report is remarkably self-aware and willing to explore the dangers” of data purchases. The panel admitted that this data can be used to “facilitate blackmail, stalking, harassment, and public shaming.” Director Haines’ new policy orders all 18 intelligence agencies to devise safeguards “tailored to the sensitivity of the information” and produce an annual report on how each agency uses such data. The policy also requires agencies:

Details for how each of the intelligence agencies will fulfill these aspirations – and actually handle “sensitive CAI” – is left up to them. Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR) acknowledged that this new policy marks “an important step forward in starting to bring the intelligence community under a set of principles and polices, and in documenting all the various programs so that they can be overseen.” Journalist and author Byron Tau told Reason that the new policy is a notable change in the government’s stance. Earlier, “government lawyers were saying basically it’s anonymized, so no privacy problem here.” Critics were quick to point out that any of this data could be deanonymized with a few keystrokes. Now, Tau says, the new policy is “sort of a recognition that this data is actually sensitive, which is a bit of change.” Tau has it right – this is a bit of a change, but one with potentially big consequences. One of those consequences is that the public and Congress will have metrics that are at least suggestive of what data the intelligence community is purchasing and how it uses it. In the meantime, Sen. Wyden says, the framework of the new policy has an “absence of clear rules about what commercially available information can and cannot be purchased by the intelligence community.” Sen. Wyden adds that this absence “reinforces the need for Congress to pass legislation protecting the rights of Americans.” In other words, the Senate must pass the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, which would subject purchased data to the same standard as any other personal information – a probable cause warrant. That alone would clarify all the rules of the intelligence community. But Who Will Fine the FBI? The Federal Communications Commission on Monday fined four wireless carriers – Verizon, AT&T, Sprint, and T-Mobile – nearly $200 million for sharing the location data of customers, often in real-time, without their consent.

The case is an outgrowth of an investigation that began during the Trump Administration following public complaints that customers’ movements were being shared in real time with third-party companies. This is sensitive data. As FCC Chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel said, consumers’ real-time location data reveals “where they go and who they are.” The carriers, FCC declared, attempted to offload “obligations to obtain customer consent onto downstream recipients of location information, which in many instances meant that no valid customer consent was obtained.” The telecoms complain that the fines are excessive and ignore steps the companies have taken to cut off bad actors and improve customer privacy. But one remark from AT&T seemed to validate FCC’s charge of “offloading.” A spokesman told The Wall Street Journal that AT&T was being held responsible for another’s company’s violations. Verizon spokesman told The Journal that it had cut out a bad actor. These spokesmen are pointing to the role of data aggregators who resell access to consumer location data and other information to a host of commercial services that want to know our daily movements. The spokesmen seem to betray a long-held industry attitude that when it sells data, it also transfers liability, including the need for customer consent. Companies of every sort that sell data, not just telecoms, will now need to study this case closely and determine whether they should tighten control over what happens to customer data after it is sold. But there is one glaring omission in the FCC’s statement. It glides past the government’s own culpability in degrading consumer privacy. A dozen federal law enforcement and intelligence agencies, ranging from the FBI to the ATF, IRS, and Department of Homeland Security, routinely purchase and access Americans’ personal, digital information without bothering to secure a warrant. Concern over this practice is what led the House to recently pass The Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, which would require government agencies to obtain warrants before buying Americans’ location and other personal data from these same data brokers. It is good to see the FCC looking out for consumers. But who is going to fine the FBI? We needed a little perspective before reporting on the historic showdown on the reauthorization of FISA Section 702 that ended on April 19 with a late-night Senate vote. The bottom line: The surveillance reform coalition finally made it to the legislative equivalent of the Super Bowl. We won’t be taking home any Super Bowl rings, but we made a lot of yardage and racked up impressive touchdowns.

For years, PPSA has coordinated with a wide array of leading civil liberties organizations across the ideological spectrum toward that key moment. We worked hard and enjoyed the support of our followers in flooding Congress with calls and emails supporting privacy and surveillance reform. So what was the result? We failed to get a warrant requirement for Section 702 data but came within one vote of winning it in the House. There was a lot of good news and new reforms that should not be overlooked. And where the news was bad, there are silver linings that gleam.

We come out of this legislative fracas bloodied but energized. We put together a durable left-right coalition in which House Judiciary Committee Chairman Jim Jordan and Ranking Member Jerry Nadler, as well as the heads of the Freedom and Progressive caucuses, who worked side-by-side. For the first time, our surveillance coalition had the intelligence community and their champions on the run. We lost the warrant provision for Section 702 only by a tie vote. Had every House Member who supported our position been in attendance, we would have won. This bodes well for the next time Section 702 reauthorization comes up. We will be ready. Let’s not forget that a recent bipartisan YouGov poll shows that 80 percent of Americans support warrant requirements. We sense a gathering of momentum – and we look forward to preparing for the next big round in April 2026. A recent House hearing on the protection of journalistic sources veered into startling territory.

As expected, celebrated investigative journalist Catherine Herridge spoke movingly about her facing potential fines of up to $800 a day and a possible lengthy jail sentence as she faces a contempt charge for refusing to reveal a source in court. Herridge said one of her children asked, “if I would go to jail, if we would lose our house, and if we would lose our family savings to protect my reporting source.” Herridge later said that CBS News’ seizure of her journalistic notes after laying her off felt like a form of “journalistic rape.” Witnesses and most members of the House Judiciary subcommittee on the Constitution and Limited Government agreed that the Senate needs to act on the recent passage of the bipartisan Protect Reporters from Exploitative State Spying (PRESS) Act. This bill would prevent federal prosecutors from forcing journalists to burn their sources, as well to bar officials from surveilling phone and email providers to find out who is talking to journalists. Sharyl Attkisson, like Herridge a former CBS News investigative reporter, brought a dose of reality to the proceeding, noting that passing the PRESS Act is just the start of what is needed to protect a free press. “Our intelligence agencies have been working hand in hand with the telecommunications firms for decades, with billions of dollars in dark contracts and secretive arrangements,” Attkisson said. “They don’t need to ask the telecommunications firms for permission to access journalists’ records, or those of Congress or regular citizens.” Attkisson recounted that 11 years ago CBS News officially announced that Attkisson’s work computer had been targeted by an unauthorized intrusion. “Subsequent forensics unearthed government-controlled IP addresses used in the intrusions, and proved that not only did the guilty parties monitor my work in real time, they also accessed my Fast and Furious files, got into the larger CBS system, planted classified documents deep in my operating system, and were able to listen in on conversations by activating Skype audio,” Attkisson said. If true, why would the federal government plant classified documents in the operating system of a news organization unless it planned to frame journalists for a crime? Attkisson went to court, but a journalist – or any citizen – has a high hill to climb to pursue an action against the federal government. Attkisson spoke of the many challenges in pursuing a lawsuit against the Department of Justice. “I’ve learned that wrongdoers in the federal government have their own shield laws that protect them from accountability,” Attkisson said. “Government officials have broad immunity from lawsuits like mine under a law that I don’t believe was intended to protect criminal acts and wrongdoing but has been twisted into that very purpose. “The forensic proof and admission of the government’s involvement isn’t enough,” she said. “The courts require the person who was spied on to somehow produce all the evidence of who did what – prior to getting discovery. But discovery is needed to get more evidence. It’s a vicious loop that ensures many plaintiffs can’t progress their case even with solid proof of the offense.” Worse, Attkisson testified that a journalist “who was spied on has to get permission from the government agencies involved in order to question the guilty agents or those with information, or to access documents. It’s like telling an assault victim that he has to somehow get the attacker’s permission in order to obtain evidence. Obviously, the attacker simply says no. So does the government.” This hearing demonstrated how important Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable searches and seizures are to the First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of the press. If Attkisson’s claims are true, the government explicitly violated a number of laws, not the least of which is mishandling classified documents and various cybercrimes. And it relies on specious immunities and privileges to avoid any accountability for its apparent crimes. Two proposed laws are a good way to start reining in such government misconduct. The first is the PRESS Act, which would protect journalists’ sources against being pressured by prosecutors in federal court to reveal their sources. The second proposed law is the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, which passed the House last week. This bill would require the government to get a warrant before it can inspect our personal, digital information sold by data brokers. And, of course, these and other laws limiting government misconduct need genuine remedies and consequences for misconduct, not the mirage of remedies enfeebled by improper immunities. PPSA Calls on Senate to End Data Purchases The House voted 219-199 to pass the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, which requires the FBI and other federal agencies to obtain a warrant before they can purchase Americans’ personal data, including internet records and location histories.

“Every American should celebrate this strong victory in the House of Representatives today,” said Bob Goodlatte, former House Judiciary Chairman and PPSA Senior Policy Advisor. “We commend the House for stepping up to protect Americans from a government that asserts a right to purchase the details of our daily lives from shady data brokers. This vote serves notice on the government that a new day is dawning. It is time for the intelligence community to respect the will of the American people and the authority of the Fourth Amendment.” Federal agencies, from the FBI to the IRS, ATF, and the Departments of Defense and Homeland Security, for years have purchased Americans’ sensitive, personal information scraped from apps and sold by data brokers. This practice is authorized by no specific statute, nor conducted under any judicial oversight. “The Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act puts an end to the peddling of Americans’ private lives to the government,” said Gene Schaerr, general counsel of PPSA. “Eighty percent of the American people in a recent YouGov poll say they believe warrants are absolutely necessary before their digital lives can be reviewed by the government. It is now the duty of the U.S. Senate to finish the job and express the will of the people.” PPSA is grateful to Rep. Warren Davidson, House Judiciary Chairman Jim Jordan, Ranking Member Jerry Nadler, Reps. Andy Biggs, Rep. Pramila Jayapal, Rep. Zoe Lofgren, Rep. Thomas Massie, Rep. Sara Jacobs, and many others who worked to persuade Members to pass this bill in such a strong bipartisan victory. Much of the credit also goes to PPSA’s followers, thousands of whom called and emailed Members of the House at a critical time. “We will need you again when the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act goes to the Senate,” Schaerr said. “Stay tuned.” Our digital traces can be put together to tell the stories of our lives. They reveal our financial and health status, our romantic activities, our religious beliefs and practices, and our political beliefs and activities.

Our location histories are no less personal. Data from the apps on our phone record where we go and with whom we meet. Taken all together, our data creates a portrait of our lives that is more intimate than a diary. Incredibly, such information is, in turn, sold by data brokers to the FBI, IRS, the Drug Enforcement Administration, the Department of Defense, the Department of Homeland Security, and other federal agencies to freely access. The Constitution’s Fourth Amendment forbids such unreasonable searches and seizures. Yet federal agencies maintain they have the right to collect and examine our personal information – without warrants. A recent report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence shows that:

The American people are alarmed. Eighty percent of Americans in a recent YouGov poll say Congress should require government agencies to obtain a warrant before purchasing location information, internet records, and other sensitive data about people in the U.S. from data brokers. The Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act now up for a vote in the House would prohibit law enforcement and intelligence agencies from purchasing certain sensitive information from third-party sellers, including geolocation information and communications-related information that is protected under the Electronic Communications Privacy Act, and information obtained from illicit data scraping. This bill balances Americans’ civil liberties with national security, giving law enforcement and intelligence agencies the ability to access this information with a warrant, court order, or subpoena. Call your U.S. House Representative and say: “Please protect my privacy by voting for the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act.” Forbes reports that federal authorities were granted a court order to require Google to hand over the names, addresses, phone numbers, and user activities of internet surfers who were among the more than 30,000 viewers of a post. The government also obtained access to the IP addresses of people who weren’t logged onto the targeted account but did view its video.

The post in question is suspected of being used to promote the sale of bitcoin for cash, which would be a violation of money-laundering rules. The government likely had good reason to investigate that post. But did it have to track everyone who came into contact with it? This is a prime example of the government’s street-sweeper shotgun approach to surveillance. We saw this when law enforcement in Virginia tracked the location histories of everyone in the vicinity of a robbery. A state judge later found that search meant that everyone in the area, from restaurant patrons to residents of a retirement home, had “effectively been tailed.” We saw the government shotgun approach when the FBI secured the records of everyone in the Washington, D.C., area who used their debit or credit cards to make Bank of America ATM withdrawals between Jan. 5 and Jan. 7, 2021. We also saw it when the FBI, searching for possible foreign influence in a congressional campaign, used FISA Section 702 data – meant to surveil foreign threats on foreign soil – to pull the data of 19,000 political donors. Surfing the web is not inherently suspicious. What we watch online is highly personal, potentially revealing all manner of social, romantic, political, and religious beliefs and activities. The Founders had such dragnet-style searches precisely in mind when they crafted the Fourth Amendment. Simply watching a publicly posted video is not by itself probable cause for search. It should not compromise one’s Fourth Amendment rights. Byron Tau – journalist and author of Means of Control, How the Hidden Alliance of Tech and Government Is Creating a New American Surveillance State – discusses the details of his investigative reporting with Liza Goitein, senior director of the Brennan Center for Justice's Liberty & National Security Program, and Gene Schaerr, general counsel of the Project for Privacy and Surveillance Accountability.

Byron explains what he has learned about the shadowy world of government surveillance, including how federal agencies purchase Americans’ most personal and sensitive information from shadowy data brokers. He then asks Liza and Gene about reform proposals now before Congress in the FISA Section 702 debate, and how they would rein in these practices. The reform coalition on Capitol Hill remains determined to add strong amendments to Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). But will they get the chance before an April 19th deadline for FISA Section 702’s reauthorization?

There are several possible scenarios as this deadline closes. One of them might be a vote on the newly introduced “Reforming Intelligence and Securing America” (RISA) Act. This bill is a good-faith effort to represent the narrow band of changes that the pro-reform House Judiciary Committee and the status quo-minded House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence could agree upon. But is it enough? RISA is deeply lacking because it leaves out two key reforms.

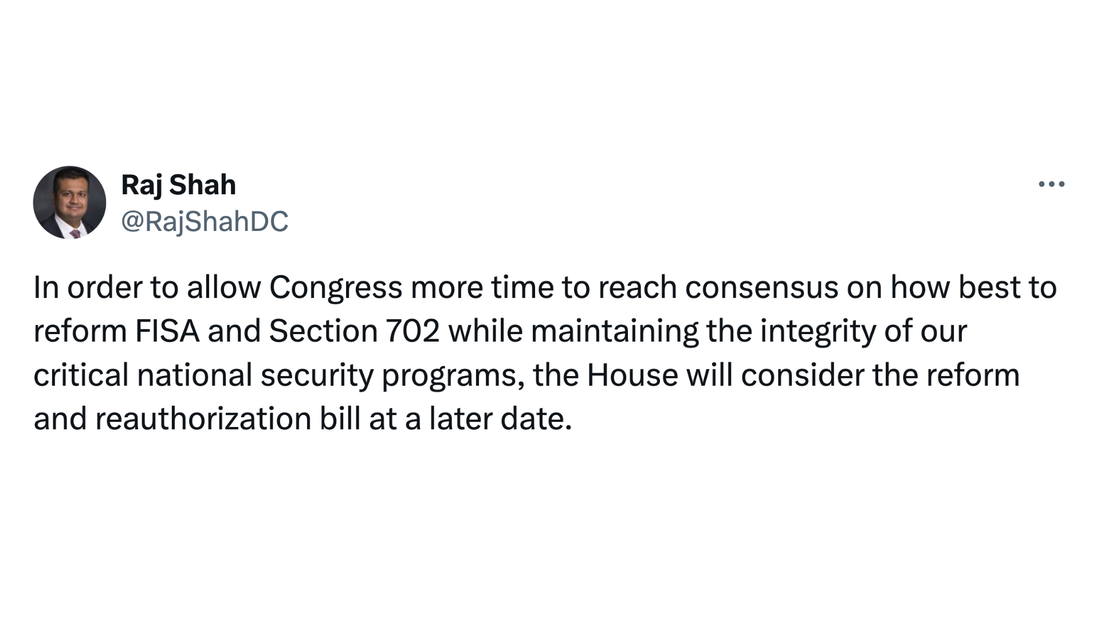

The bill does include a role for amici curiae, specialists in civil liberties who would act as advisors to the secret FISA court. RISA, however, would limit the issues these advisors could address, well short of the intent of the Senate when it voted 77-19 in 2020 to approve the robust amici provisions of the Lee-Leahy amendment. For all these reasons, reformers should see RISA as a floor, not as a ceiling, as the Section 702 showdown approaches. The best solution to the current impasse is to stop denying Members of Congress the opportunity for a straight up-or-down vote on reform amendments. The contest between surveillance reformers and defenders of domestic surveillance is set to come to a showdown in the second week of April. Speaker Mike Johnson told Politico that his “current plan is to run FISA as a standalone the week after Easter.” Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) allows federal agencies to gather foreign intelligence but has been used by the government to conduct domestic surveillance on millions of Americans in recent years. Its reauthorization, with or without reforms, will almost certainly come to a vote before its expiration on April 19. The big question is whether the House will be allowed vote on two reform amendments. These amendments would impose warrant requirements before federal agencies could inspect the communications of Americans caught up in the global trawl of intelligence agencies, as well as for the sensitive, personal information of Americans scraped by apps and sold by data brokers to the government. These amendments are backed by strong bipartisan support that spans across the aisle and includes leaders of the Freedom and Progressive caucuses. The odds of votes on reform amendment on the House floor increased with renewed pressure for reform coming from the Senate. Sens. Dick Durbin (D-IL) and Mike Lee (R-UT) introduced the Security and Freedom Enhancement (SAFE) Act, which includes the prime provisions of House reformers, with a few pragmatic concessions to the needs of intelligence practitioners. The route to this moment has been long and tortuous. The House reauthorization bill, and a chance to vote on the two warrant amendments, was pulled at the request of the intelligence community in February when it became clear these measures likely had majority support. With powerful bipartisan support for reform now coming from two respected lawmakers on the Senate Judiciary Committee, it will be hard to stiff-arm reformers again in either chamber. That doesn’t mean it cannot happen. Expect the champions of the surveillance status quo to come up with new legislative tricks and scares (remember the Putin space nuke debacle?) before April’s vote. PPSA will be tracking every development in this struggle. Registering your determination for surveillance reform now will help maintain the “current plan” for reauthorization, debate, and vote on reform amendments. Tell your U.S. House Representative:“Stop the FBI and other government agencies from spying on innocent Americans. Please fight for a vote to reform FISA’s Section 702 with warrant requirements, both for Section 702 data and for our sensitive, personal information sold to the government by data brokers.” Our general counsel, Gene Schaerr, explains in the Washington Examiner how the Biden administration's recent executive order to protect personal data from government abuse falls short. Hint: It excludes our very own government's abuse of our personal data.

How to Tell if You are Being Tracked Car companies are collecting massive amounts of data about your driving – how fast you accelerate, how hard you brake, and any time you speed. These data are then analyzed by LexisNexis or another data broker to be parsed and sold to insurance companies. As a result, many drivers with clean records are surprised with sudden, large increases in their car insurance payments.

Kashmir Hill of The New York Times reports the case of a Seattle man whose insurance rates skyrocketed, only to discover that this was the result of LexisNexis compiling hundreds of pages on his driving habits. This is yet another feature of the dark side of the internet of things, the always-on, connected world we live in. For drivers, internet-enabled services like navigation, roadside assistance, and car apps are also 24-7 spies on our driving habits. We consent to this, Hill reports, “in fine print and murky privacy policies that few read.” One researcher at Mozilla told Hill that it is “impossible for consumers to try and understand” policies chocked full of legalese. The good news is that technology can make data gathering on our driving habits as transparent as we are to car and insurance companies. Hill advises:

What you cannot do, however, is file a report with the FBI, IRS, the Department of Homeland Security, or the Pentagon to see if government agencies are also purchasing your private driving data. Given that these federal agencies purchase nearly every electron of our personal data, scraped from apps and sold by data brokers, they may well have at their fingertips the ability to know what kind of driver you are. Unlike the private snoops, these federal agencies are also collecting your location histories, where you go, and by inference, who you meet for personal, religious, political, or other reasons. All this information about us can be accessed and reviewed at will by our government, no warrant needed. That is all the more reason to support the inclusion of the principles of the Fourth Amendment Is Not for Sale Act in the reauthorization of the FISA Section 702 surveillance policy. While Congress debates adding reforms to FISA Section 702 that would curtail the sale of Americans’ private, sensitive digital information to federal agencies, the Federal Trade Commission is already cracking down on companies that sell data, including their sales of “location data to government contractors for national security purposes.”

The FTC’s words follow serious action. In January, the FTC announced proposed settlements with two data aggregators, X-Mode Social and InMarket, for collecting consumers’ precise location data scraped from mobile apps. X-Mode, which can assimilate 10 billion location data points and link them to timestamps and unique persistent identifiers, was targeted by the FTC for selling location data to private government contractors without consumers’ consent. In February, the FTC announced a proposed settlement with Avast, a security software company, that sold “consumers’ granular and re-identifiable browsing information” embedded in Avast’s antivirus software and browsing extensions. What is the legal basis for the FTC’s action? The agency seems to be relying on Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act, which grants the FTC power to investigate and prevent deceptive trade practices. In the case of X-Mode, the FTC’s proposed complaint highlight’s X-Mode’s statement that their location data would be used solely for “ad personalization and location-based analytics.” The FTC alleges X-Mode failed to inform consumers that X-Mode “also sold their location data to government contractors for national security purposes.” The FTC’s evolving doctrine seems even more expansive, weighing the stated purpose of data collection and handling against its actual use. In a recent blog, the FTC declares: “Helping people prepare their taxes does not mean tax preparation services can use a person’s information to advertise, sell, or promote products or services. Similarly, offering people a flashlight app does not mean app developers can collect, use, store, and share people’s precise geolocation information. The law and the FTC have long recognized that a need to handle a person’s information to provide them a requested product or service does not mean that companies are free to collect, keep, use, or share that’s person’s information for any other purpose – like marketing, profiling, or background screening.” What is at stake for consumers? “Browsing and location data paint an intimate picture of a person’s life, including their religious affiliations, health and medical conditions, financial status, and sexual orientation.” If these cases go to court, the tech industry will argue that consumers don’t sign away rights to their private information when they sign up for tax preparation – but we all do that routinely when we accept the terms and conditions of our apps and favorite social media platforms. The FTC’s logic points to the common understanding that our data is collected for the purpose of selling us an ad, not handing over our private information to the FBI, IRS, and other federal agencies. The FTC is edging into the arena of the Fourth Amendment Is Not for Sale Act, which targets government purchases and warrantless inspection of Americans’ personal data. The FTC’s complaints are, for the moment, based on legal theory untested by courts. If Congress attaches similar reforms to the reauthorization of FISA Section 702, it would be a clear and hard to reverse protection of Americans’ privacy and constitutional rights. Ken Blackwell, former ambassador and mayor of Cincinnati, has a conservative resume second to none. He is now a senior fellow of the Family Research Council and chairman of the Conservative Action Project, which organizes elected conservative leaders to act in unison on common goals. So when Blackwell writes an open letter in Breitbart to Speaker Mike Johnson warning him not to try to reauthorize FISA Section 702 in a spending bill – which would terminate all debate about reforms to this surveillance authority – you can be sure that Blackwell was heard.

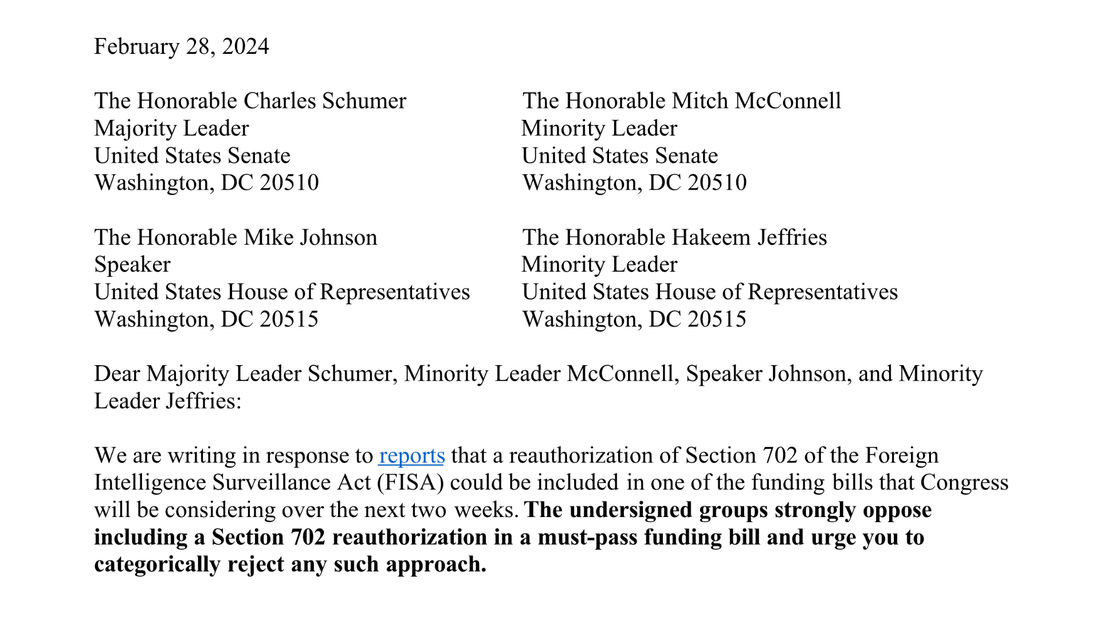

“The number of FISA searches has skyrocketed with literally hundreds of thousands of warrantless searches per year – many of which involve Americans,” Blackwell wrote. “Even one abuse of a citizen’s constitutional rights must not be tolerated. When that number climbs into the thousands, Congress must step in.” What makes Blackwell’s appeal to Speaker Johnson unique is he went beyond including the reform efforts from conservative stalwarts such as House Judiciary Committee Chairman Jim Jordan and Rep. Andy Biggs of the Freedom Caucus. Blackwell also cited the support from the committee’s Ranking Member, Rep. Jerry Nadler, and Rep. Pramila Jayapal, who heads the House Progressive Caucus. Blackwell wrote: “Liberal groups like the ACLU support reforming FISA, joining forces with conservatives civil rights groups. This reflects a consensus almost unseen on so many other important issues of our day. Speaker Johnson needs to take note of that as he faces pressure from some in the intelligence community and their overseers in Congress, who are calling for reauthorizing this controversial law without major reforms and putting that reauthorization in one of the spending bills that will work its way through Congress this month.” That is sound advice for all Congressional leaders on Section 702, whichever side of the aisle they are on. In December, members of this left-right coalition joined together to pass reform measures out of the House Judiciary Committee by an overwhelming margin of 35 to 2. This reform coalition is wide-ranging, its commitment is deep, and it is not going to allow a legislative maneuver to deny Members their right to a debate. PPSA, in concert with a coalition of major civil liberties groups from the left, right, and center, is appealing to Members of Congress “to oppose any legislative end-run that allows the FBI and other intelligence agencies to continue to spy on Americans without giving Congress the opportunity to vote on reforms.”

The word from Capitol Hill is that the intelligence community is now lobbying to attach a reauthorization of FISA Section 702 to a “must-pass” spending measure. Such a maneuver would cement the intelligence community’s strategy of denying Members of Congress a chance to have a debate and to vote on reforms to this surveillance authority. Our letter, which includes Americans for Prosperity, the Brennan Center for Justice, Demand Progress, FreedomWorks, and the Wikimedia Foundation, warns Congress: “The Fourth Amendment will become a constitutional dead letter if the government can continue to track our every movement, communications, where we worship, our financial and health issues, what we believe, and our political activity without warrants.” Our letter concludes: “Congress must be able to vote on reforms rather than being faced with a ‘take-it-or-leave-it’ choice between funding the government and protecting Americans’ liberties.” Our FISA Reform Coalition letter ended by urging Congress to stand up for Americans’ privacy, the Constitution, and against the insulting premise that Members of Congress should not be allowed to vote on surveillance reform. Tell your Representative in the U.S. House that you want the FBI and other federal intelligence agencies to stop spying on you and your family.

In recent years, the FBI and other agencies have freely dipped into Americans’ private communications and data caught up in foreign surveillance. The FBI, IRS, Drug Enforcement Administration, Pentagon, and other agencies also track your every move by purchasing your geolocation data and other sensitive, personal information scraped from the apps on your cellphone and sold to the government by shady data brokers. Your personal information from these sources tells the FBI where you’ve been and where you’re going, where you worship, who you date or have fun with, and all about your health, financial information, personal beliefs, and political activities. Do you trust this government to have so much power over your life? Consider that the FBI has already been caught dipping into Americans’ personal communications in recent years by the millions. The government has followed our political and religious activities for years without warrants, spied on 19,000 donors to a Congressional campaign, and spied on a state senator, a state judge, a U.S. Congressman, and U.S. Senator. If judges and Members of Congress can have their rights violated, imagine how much respect the FBI and other government agencies have for your privacy. For now, champions of the intelligence community on Capitol Hill have used a legislative maneuver to prevent a vote that would require the government to get warrants before looking at your private information. The FBI and their friends know that if these amendments get a fair vote on the House floor, they will lose. So they’ve upended the whole process. This is dirty pool. The lack of a vote denies your Member of Congress the right to debate and vote for reform. Unchallenged, this maneuver ensures that the FBI and other agencies will continue to ignore the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which clearly mandates that the government go to a court and obtain a warrant before your personal communications can be inspected. So tell your U.S. House Representative to demand that the FBI and other federal agencies stop accessing your private, personal communications and data without a warrant. Tell your U.S. House Representative: “Stop the FBI from spying on innocent Americans. Please fight for a vote to reform FISA’s Section 702 with warrant requirements, both for Section 702 data and for our sensitive, personal information sold to the government by data brokers.” When we covered a Michigan couple suing their local government for sending a drone over their property to prove a zoning violation, we asked if there are any legal limits to aerial surveillance of your backyard.

In this case before the Michigan Supreme Court, Maxon v. Long Lake Township, counsel for the local government said that the right to inspect our homes goes all the way to space. He described the imaging capability of Google Earth satellites, asking: “If you want to know whether it’s 50 feet from this house to this barn, or 100 feet from this house to this barn, you do that right on the Google satellite imagery. And so given the reality of the world we live in, how can there be a reasonable expectation of privacy in aerial observations of property?” One justice reacted to the assertion that if Google Earth could map a backyard as closely and intimately as a drone, that would be a search. “Technology is rapidly changing,” the justice responded. “I don’t think it is hard to predict that eventually Google Earth will have that capacity.” Now William J. Broad of The New York Times reports that we’re well beyond Google Earth’s imaging of barns and houses. Try dinner plates and forks. Albedo Space of Denver is making a fleet of 24 small, low orbit satellites that will use imagery to guide responders in disasters, such as wildfires and other public emergencies. It will improve the current commercial standard of satellite imaging from a focal length of about a foot to about four inches. A former CIA official with decades of satellite experience told Broad that it will be a “big deal” when people realize that anything they are trying to hide in their backyards will be visible. Skinny-dipping in the pool will only be for the supremely confident. To his credit, Albedo chief Topher Haddad said, “we’re acutely aware of the privacy implications,” promising that management will be selective in their choice of clients on a case-by-case basis. It is good to know that Albedo likely won’t be using its technology to catch zone violators or backyard sunbathers. We’ve seen, however, that what is cutting-edge technology today will be standard tomorrow. This is just one more way in which the velocity of technology is outpacing our ability to adjust. There is, of course, one effective response. We can reject the Michigan town’s counsel argument who said, essentially, that privacy’s dead and we should just get over it. Courts and Congress should define orbital and aerial surveillance as searches requiring a probable cause warrant, as defined by the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, before our homes and backyards can be invaded by eyes from above. The greatest danger to privacy is not that Albedo will allow government snoops to watch us in real time. The real threat is a satellite company’s ability to collect private images by the tens of millions. Such a database could then be sold to the government just as so much commercial digital information is now being sold to the government by data brokers. This is all the more reason for Congress to import the privacy-protecting warrant provisions of the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act into the reauthorization of FISA Section 702. Just in time for the Section 702 debate, Emile Ayoub and Elizabeth Goitein of the Brennan Center for Justice have written a concise and easy to understand primer on what the data broker loophole is about, why it is so important, and what Congress can do about it.

These authors note that in this age of “surveillance capitalism” – with a $250 billion market for commercial online data – brokers are compiling “exhaustive dossiers” that “reveal the most intimate details of our lives, our movements, habits, associations, health conditions, and ideologies.” This happens because data brokers “pay app developers to install code that siphons users’ data, including location information. They use cookies or other web trackers to capture online activity. They scrape from information public-facing sites, including social media platforms, often in violation of those platforms’ terms of service. They also collect information from public records and purchase data from a wide range of companies that collect and maintain personal information, including app developers, internet service providers, car manufacturers, advertisers, utility companies, supermarkets, and other data brokers.” Armed with all this information, data brokers can easily “reidentify” individuals from supposedly “anonymized” data. This information is then sold to the FBI, IRS, the Drug Enforcement Administration, the Department of Defense, the Department of Homeland Security, and state and local law enforcement. Ayoub and Goitein examine how government lawyers employ legal sophistry to evade a U.S. Supreme Court ruling against the collection of location data, as well as the plain meaning of the U.S. Constitution, to access Americans’ most personal and sensitive information without a warrant. They describe the merits of the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, and how it would shut down “illegitimately obtained information” from companies that scrape photos and data from social media platforms. The latter point is most important. Reformers in the House are working hard to amend FISA Section 702 with provisions from the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, to require the government to obtain warrants before inspecting our commercially acquired data. While the push is on to require warrants for Americans’ data picked up along with international surveillance, the job will be decidedly incomplete if the government can get around the warrant requirement by simply buying our data. Ayoub and Goitein conclude that Congress must “prohibit government agencies from sidestepping the Fourth Amendment.” Read this paper and go here to call your House Member and let them know that you demand warrants before the government can access our sensitive, personal information. From Gene Schaerr, general counsel of the Project for Privacy and Surveillance Accountability:

“For months, the House Intelligence Committee warned that failure to reauthorize Section 702 would subject the American homeland to unprecedented danger. “Now the Intelligence Committee has caused the bill to be pulled rather than allow the House to work its will and vote on a few reasonable and important reform amendments. “They are now willing to endanger Section 702 in its entirety unless they get everything they want. “Think about it – the intelligence community and deep state are so determined to maintain the ability to spy on Americans that they are willing to put at risk the very authority they claim they need to protect us against foreign threats.” The word from Capitol Hill is that Speaker Mike Johnson is scheduling a likely House vote on the reauthorization of FISA’s Section 702 this week. We are told that proponents and opponents of surveillance reform will each have an opportunity to vote on amendments to this statute.

It is hard to overstate how important this upcoming vote is for our privacy and the protection of a free society under the law. The outcome may embed warrant requirements in this authority, or it may greatly expand the surveillance powers of the government over the American people. Section 702 enables the U.S. intelligence community to continue to keep a watchful eye on spies, terrorists, and other foreign threats to the American homeland. Every reasonable person wants that, which is why Congress enacted this authority to allow the government to surveil foreign threats in foreign lands. Section 702 authority was never intended to become what it has become: a way to conduct massive domestic surveillance of the American people. Government agencies – with the FBI in the lead – have used this powerful, invasive authority to exploit a backdoor search loophole for millions of warrantless searches of Americans’ data in recent years. In 2021, the secret Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court revealed that such backdoor searches are used by the FBI to pursue purely domestic crimes. Since then, declassified court opinions and compliance reports reveal that the FBI used Section 702 to examine the data of a House Member, a U.S. Senator, a state judge, journalists, political commentators, 19,000 donors to a political campaign, and to conduct baseless searches of protesters on both the left and the right. NSA agents have used it to investigate prospective and possible romantic partners on dating apps. Any reauthorization of Section 702 must include warrants – with reasonable exceptions for emergency circumstances – before the data of Americans collected under Section 702 or any other search can be queried, as required by the U.S. Constitution. This warrant requirement must include the searching of commercially acquired information, as well as data from Americans’ communications incidentally caught up in the global communications net of Section 702. The FBI, IRS, Department of Homeland Security, the Pentagon, and other agencies routinely buy Americans’ most personal, sensitive information, scraped from our apps and sold to the government by data brokers. This practice is not authorized by any statute, or subject to any judicial review. Including a warrant requirement for commercially acquired information as well as Section 702 data is critical, otherwise the closing of the backdoor search loophole will merely be replaced by the data broker loophole. If the House declines to impose warrants for domestic surveillance, expect many politically targeted groups to have their privacy and constitutional rights compromised. We cannot miss the best chance we’ll have in a generation to protect the Constitution and what remains of Americans’ privacy. Copy and paste the message below and click here to find your U.S. Representative and deliver it: “Please stand up for my privacy and the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Vote to reform FISA’s Section 702 with warrant requirements, both for Section 702 data and for our sensitive, personal information sold to government agencies by data brokers.” |

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed