PPSA Asks Supreme Court to Hear X Corp.’s Constitutional Case Against Surveillance Gag Orders7/10/2024

PPSA announced today the filing of an amicus brief asking the U.S. Supreme Court to take up a case in which X Corp., formerly Twitter, objects to surveillance and gag orders that violate the First Amendment and pose a threat to the Fourth and Sixth Amendments as well.

When many consumers think of their digital privacy, they think first of what’s on their computers and shared with others by text or email. But the complex, self-regulating network that is the internet is not so simple. Our online searches, texts, images, and emails – including sensitive, personal information about health, mental health, romances, and finances – are backed up on the “cloud,” including data centers like X Corp.’s that distribute storage and computing capacity. Therein lies the greatest vulnerability for government snooping. The growth of data centers is prolific, rising from 2,600 to 5,300 such centers in 2024. And with it, so have government demands for our data. When federal agencies – often without a warrant – seek to access Americans’ personal data, more often than not they go to the companies that store the data in places like these data centers. For years, this power involved large social media and telecom companies. The power of the government to extract data, already robust, increased exponentially with the reauthorization of FISA Section 702 in April, which included what many call the “Make Everyone a Spy Act.” This provision defines an electronic communication service provider as virtually any company that merely has access to equipment, like Wi-Fi and routers, that is used to transmit or store electronic communications. On top of that, the government then slaps the data center or service provider with a Non-Disclosure Order (NDO), a gag order that prevents the company from informing customers that their private information has been reviewed. One such company – X Corp. – has been pressing a constitutional challenge against this practice regarding a government demand for former President Trump’s account data. PPSA has joined in an amicus brief supporting X’s bid for certiorari, asking the Court to consider the constitutional objections to government conscription of companies that host consumers’ data as adjunct spies, while restraining their ability to speak out on this conscription. In the case of X, the government has seized the company’s records on customer communications and then slapped the company with an NDO to force it to shut up about it. The government claims this secrecy is needed to protect the investigation, even though the government itself has already publicized the details of its investigation. Whatever you think of Donald Trump, this is an Orwellian practice. PPSA’s amicus brief informed the Court that the gag order “makes a mockery of the First Amendment’s longstanding precedent governing prior restraints. And it will only become more frequent as third-party cloud storage becomes increasingly common for everything from business records to personal files to communications …” The brief informs the Court: “NDOs can be used to undermine other constitutionally protected rights” beyond the First Amendment. These rights include the short-circuiting of Fourth Amendment rights against warrantless searches and Sixth Amendment rights to a public trial in which a defendant can know the evidence against him. Partial solutions to these short-comings are winding their way through the legislative process. Sen. Mark Warner, Chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, introduced legislation to narrow the scope of businesses covered by the new, almost-universal dragooning of businesses large and small as government spies – though House Intelligence Chairman Mike Turner is opposing that reasonable provision. Last year, the House passed the NDO Fairness Act, which requires judicial review and limited disclosures for these restraints on speech and privacy. As partial solutions wend their way through Congress, this case presents a number of well-defined concerns best defined by the Supreme Court. PPSA today announced the filing of a lawsuit to compel the FBI to produce records about the possible use of FISA Section 702 authority – enacted by Congress to enable surveillance of foreign targets on foreign soil – for political surveillance of Americans at home.

Activists on the left and the right have long suspected the FBI uses surreptitious means to spy on lawful protests and speech. Those suspicions were confirmed when a FISA court decision released in 2022 revealed that government investigators had used Section 702 global database to surveil all 19,000 donors to a single Congressional campaign. Acting on this concern, PPSA submitted a FOIA request to the FBI in February seeking all records discussing the use of Section 702 or other FISA authorities to surveil, collect information related to, or otherwise investigate anyone who attended:

The FBI almost immediately responded to PPSA that our FOIA request “is not searchable” in the FBI’s “indices.” The response also informed us that the FBI “administratively closed” our request. The FBI did not dispute that PPSA’s FOIA request reasonably described the requested records. This should have, under the FOIA statute, triggered a search requirement, but the FBI ignored it. The self-serving excuse that limitations to the FBI’s Central Records System overlooks the plentiful databases and search methods at the fingertips of one of the world’s premier investigative organizations. After a fruitless appeal to the Department of Justice’s Office of Information Policy, exhausting any administrative remedy, PPSA is now suing in the U.S. District Court of the District of Columbia to compel the FBI to produce these documents. We’ll keep you informed of any major developments. For the second time, PPSA has been forced to go to court to oppose the delaying tactics of the National Security Agency, the CIA, the FBI, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence in complying with its obligations under Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

PPSA’s FOIA request, now years old, asks these agencies to produce documents concerning their acquisition and use of commercially available information regarding 145 current and former Members of Congress. These Members have served on committees with oversight responsibilities of the intelligence community. Earlier this year, federal Judge Rudolph Contreras rejected the agencies’ insistence that the Glomar doctrine – which allows agencies to neither confirm nor deny the existence of certain records – relieves them of their statutory obligations to search for responsive records. Judge Contreras had narrowed PPSA’s request to exclude operational documents, ordering agencies to search for only policy documents. He cited agencies correspondence with Members of Congress as an example of a policy document. Judge Contreras wrote, “it is difficult to see how a document such as this would reveal sensitive information about Defendants’ intelligence activities, sources or methods.” Yet the intelligence community is defying its legal obligations for a second time. The agencies’ new strategy rests on a nonsensical linkage to an entirely different PPSA case, currently before the D.C. Circuit, that happens to also use the term “policy documents.” By conflating separate cases, the agencies suggest that they meant to challenge Judge Contreras’ order to search only for “policy documents.” But the agencies have not done so, and this is clearly just the latest delay tactic used to ignore FOIA’s clear search requirement, which Judge Contreras reinforced earlier this year. As a result of this new attempt at delay and obfuscation, agencies are now asking the Court to significantly expand Defendants’ delays by staying this case into 2025. PPSA is hopeful that these agencies will eventually comply with a direct and unambiguous order from a federal judge. A federal court has given the go-ahead for a lawsuit filed by Just Futures Law and Edelson PC against Western Union for its involvement in a dragnet surveillance program called the Transaction Record Analysis Center (TRAC).

Since 2022, PPSA has followed revelations on a unit of the Department of Homeland Security that accesses bulk data on Americans’ money wire transfers above $500. TRAC is the central clearinghouse for this warrantless information, recording wire transfers sent or received in Arizona, California, New Mexico, Texas, and Mexico. These personal, financial transactions are then made available to more than 600 law enforcement agencies – almost 150 million records – all without a warrant. Much of what we know about TRAC was unearthed by a joint investigation between ACLU and Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR). In 2023, Gene Schaerr, PPSA general counsel, said: “This purely illegal program treats the Fourth Amendment as a dish rag.” Now a federal judge in Northern California determined that the plaintiffs in Just Future’s case allege plausible violations of California laws protecting the privacy of sensitive financial records. This is the first time a court has weighed in on the lawfulness of the TRAC program. We eagerly await revelations and a spirited challenge to this secretive program. The TRAC intrusion into Americans’ personal finances is by no means the only way the government spies on the financial activities of millions of innocent Americans. In February, a House investigation revealed that the U.S. Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) has worked with some of the largest banks and private financial institutions to spy on citizens’ personal transactions. Law enforcement and private financial institutions shared customers’ confidential information through a web portal that connects the federal government to 650 companies that comprise two-thirds of the U.S. domestic product and 35 million employees. TRAC is justified by being ostensibly about the border and the activities of cartels, but it sweeps in the transactions of millions of Americans sending payments from one U.S. state to another. FinCEN set out to track the financial activities of political extremists, but it pulls in the personal information of millions of Americans who have done nothing remotely suspicious. Groups on the left tend to be more concerned about TRAC and groups on the right, led by House Judiciary Chairman Jim Jordan, are concerned about the mass extraction of personal bank account information. The great thing about civil liberties groups today is their ability to look beyond ideological silos and work together as a coalition to protect the rights of all. For that reason, PPSA looks forward to reporting and blasting out what is revealed about TRAC in this case in open court. Any revelations from this case should sink in across both sides of the aisle in Congress, informing the debate over America’s growing surveillance state. National Rifle Association v. Vullo In this age of “corporate social responsibility,” can a government regulator mount a pressure campaign to persuade businesses to blacklist unpopular speakers and organizations? Would such pressure campaigns force banks, cloud storage companies, and other third parties that hold targeted organizations’ data to compromise their clients’ Fourth as well as their First Amendment rights?

These are just some of the questions PPSA is asking the U.S. Supreme Court to weigh in National Rifle Association v. Vullo. Here's the background on this case: Maria Vullo, then-superintendent of the New York Department of Financial Services, used her regulatory clout over banks and insurance companies in New York to strongarm them into denying financial services to the National Rifle Association. This campaign was waged under an earnest-sounding directive to consider the “reputational risk” of doing business with the NRA and firearms manufacturers. Vullo imposed consent orders on three insurers that they never again provide policies to the NRA. She issued guidance that encouraged financial services firms to “sever ties” with the NRA and to “continue evaluating and managing their risks, including reputational risks” that could arise from their dealings with the NRA or similar gun promotion organizations. “When a regulator known to slap multi-million fines on companies issues ‘guidance,’ it is not taken as a suggestion,” said Gene Schaerr, PPSA general counsel. “It’s sounds more like, ‘nice store you’ve got here, it’d be shame if anything happened to it.’” The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit reversed a lower court’s decision that found that Vullo used threats to force the companies she regulates to cut ties with the NRA. The Second Circuit reasoned that: “The general backlash against gun promotion groups and businesses … could (and likely does) directly affect the New York financial markets; as research shows, a business's response to social issues can directly affect its financial stability in this age of enhanced corporate social responsibility.” You don’t have to be an enthusiast of the National Rifle Association to see the problems with the Second Circuit’s reasoning. Aren’t executives of New York’s financial services firms better qualified to determine what does and doesn’t “directly affect financial stability” than a regulator in Albany? How aggressive will government become in using its almost unlimited access to buy or subpoena data of a target organization to get its way? We told the Court: “Even the stability of a single company is not enough; the government cannot override the Bill of Rights to slightly reduce the rate of corporate bankruptcies.” In our brief, PPSA informs the U.S. Supreme Court about the dangers of a nebulous, government-imposed “corporate social responsibility standard.” We write: “Using CSR – a controversial theory positing that taking popular or ‘socially responsible’ stances may increase corporate profits – to justify infringement of First Amendment rights poses a grave threat to all Constitutionally-protected individual rights.” PPSA is reminding the Court that the right to free speech and the right to be protected from government surveillance are intwined. Agencies Must Release Policy Documents About Purchase of the Personal Data of 145 Members of Congress Late last week, Judge Rudolph Contreras ordered the NSA, the CIA, the FBI, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence to respond to a PPSA Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. The government now has two weeks to schedule the production of “policy documents” regarding the intelligence community’s acquisition and use of commercially available information regarding 145 current and former Members of Congress.

This is the second time Judge Contreras has had to tell federal agencies to respond to a FOIA request PPSA submitted. In late 2022, Judge Contreras rejected in part the FBI’s insistence that the Glomar doctrine allowed it to ignore FOIA’s requirement to search for responsive records. Despite that clear holding, the FBI – joined this time by several other agencies – again refused to search for records in response to PPSA’s FOIA request. And Judge Contreras had to remind the agencies again that FOIA’s search obligations cannot be ducked so easily. Instead, Judge Contreras found that PPSA “logically and plausibly” requested the policy documents about the acquisition of commercially available information. And Judge Contreras concluded that a blanket Glomar response, in which the government neither confirms nor denies the existence of the requested documents, is appropriate only when a Glomar response is justified for all categories of responsive records. The judge then described a hypothetical letter from a Member of Congress to the NSA that clarifies the distinction between operational and policy documents. He considered that such a letter might ask if the NSA “had purchased commercially available information on any of the listed Senators or Congresspeople” without revealing whether the NSA (or any other of the defendant agencies) “had a particular interest in surveilling the individual.” Judge Contreras decided that “it is difficult to see how a document such as this would reveal sensitive information about Defendants’ intelligence activities, sources, or methods.” It is on this reasoning that the judge ordered these agencies to produce these policies documents. We eagerly awaits the delivery of these documents in both cases. Stay tuned. PPSA today announced that it is asking the District Court for the District of Columbia to force the FBI to produce two records about communications between government agencies and Members of Congress concerning their possible “unmasking” in secretly intercepted foreign conversations under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA).

PPSA’s request to the court involves the practice of naming Americans – in this case, Members of the House and Senate – who are caught up in foreign surveillance summaries. In 2017, Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) said he had reason to believe his identify had been unmasked and that he had written to the FBI about it. Similar statements have been made by other Members of Congress of both parties. The matter seemed to have been settled in October 2022 when Judge Rudolph Contreras of the U.S. District Court of the District of Columbia declared that “communications between the FBI and Congress are a degree removed from FISA-derived documents and which discuss congressional unmasking as a matter of legislative interest, policy, or oversight … the FBI must conduct a search for any ‘policy documents’ in its possession.” The FBI had first refused to release these documents under a broad and untenable interpretation of the Glomar doctrine, under which the government asserts it can neither confirm nor deny the existence of such records for national security reasons. After Judge Contreras swept that excuse away, the FBI in October 2023 asserted that three FOIA exemptions allow it to withhold requested documents. The FBI has gone from obfuscation to outright defiance of the plain text of the law. It still claims that releasing correspondence with Congress would, somehow, endanger intelligence sources and methods. It is time for the court to step in and issue a legal order the FBI cannot openly defy. Thus PPSA’s cross motion for summary judgment knocks down the FBI’s rationale and asks Judge Contreras to order the FBI to produce all FBI records reflecting communications between the government and Members of Congress on their “unmasking.” Earlier, the FBI had searched under a court order to find two relevant policy documents. These unreleased records include a four-page email between FBI employees and an FBI Intelligence Program Policy Guide. Significant portions of both documents are being withheld by the FBI because, the Bureau now asserts, of the three exemptions. It claims the disclosure can be withheld because it could implicate sources and methods, the records were created for law enforcement purposes, and because of confidentiality. None of these excuses meet the laugh test for correspondence with Members of Congress. PPSA is optimistic the court will end the FBI’s two years of foot-dragging and order it to produce. Every now and then, even with an outlook jaded by knowledge of the many ways we can be surveilled, we come across some new outrage and find ourselves shouting – “no, wait, they’re doing what?”

The final dismissal of a class-action lawsuit law by a federal judge in Seattle on Tuesday reveals a precise and disturbing way in which our cars are spying on us. Cars hold the contents of our texts messages and phone call records in a way that can be retrieved by the government but not by us. The judge in this case ruled that Honda, Toyota, Volkswagen, and General Motors did not meet the necessary threshold to be held in violation of a Washington State privacy law. The claim was that the onboard entertainment system in these vehicles record and intercept customers’ private text messages and mobile phone call logs. The class-action failed because the Washington Privacy Act’s standard requires a plaintiff to approve that “his or her business, his or her person, or his or her reputation” has been threatened. What emerged from this loss in court is still alarming. Software in cars made by Maryland-based Berla Corp. (slogan: “Staggering Amounts of Data. Endless Possibilities”) allows messages to be downloaded but makes it impossible for vehicle owners to access their communications and call logs. Law enforcement, however, can gain ready access to our data, while car manufacturers make extra money selling our data to advertisers. This brings to mind legislation proposed in 2021 by Sens. Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Cynthia Lummis (R-WY) along with Reps. Peter Meijer (R-MI) and Ro Khanna (D-CA). Under their proposal, law enforcement would have to obtain a warrant based on probable cause before searching data from any vehicle that does not require a commercial driver’s license. Under the “Closing the Warrantless Digital Car Search Loophole Act,” any vehicle data obtained in violation of this law would be inadmissible in court. Sen. Wyden in a statement at the time said: “Americans’ Fourth Amendment rights shouldn’t disappear just because they’ve stepped into a car.” They shouldn’t. But as this federal judge made clear, they do. “Health of Democracy at Stake""The president and the general counsel of PPSA late last night asked the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia to reverse a lower court ruling that prohibited Carter Page from suing eight federal officers who played a direct role in his illegal surveillance during the now-infamous “Crossfire Hurricane” investigation. The appeal filed by Erik Jaffe and Gene Schaerr of the Schaerr-Jaffe law firm seeks a private right of action against former FBI Director James Comey, former deputy director Andrew McCabe, and former FBI agent Peter Strzok, former FBI lawyers Lisa Page and Kevin Clinesmith, as well as three others in the FBI and Department of Justice. As described by the Justice Department’s Inspector General’s investigation into the Crossfire Hurricane case, these officials relied on the false Steele report, concocted by an opposition researcher with ties to the political party opposing Trump, in order to portray Page as a Russian agent. The defendants hid from the court the FBI’s internal misgivings about the Steele report, and CIA warnings about its reliability. These untruths were used to support four separate surveillance requests, deceiving the secret Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) court. Clinesmith later pled guilty to a felony false statement charge for doctoring a document from the CIA attesting that Carter Page was an operational contact and asset of the agency to state that Page was “not a source.” The appeal on behalf of Page asks the court to consider errors in the lower district court’s ruling, which dismissed Page’s claims without any discovery. The appeal notes that the plain language of FISA allows an aggrieved person to sue if that victim has suffered from the unlawful abuse of that authority. FISA makes it illegal to use or disclose information obtained by such illicit surveillance. The appeal also rests on the PATRIOT Act, which makes it unlawful for federal officers or employees to use or disclose such information except for lawful purposes. The appeal reads:

“This case is about holding government actors accountable for their plainly illegal conduct of using fraud and deceit to obtain secret search warrants against an innocent citizen. Worse still, such tactics were used against an innocent foreign policy advisor to a disliked presidential campaign in a transparently political effort to derail that campaign.” As a result of official leaks, Carter Page for months was derided in the mass media as a “traitor.” And that, according to attorney Gene Schaerr, was a grave injustice perpetrated by senior FBI officials: “You don’t have to be a fan of Donald Trump to understand that an FBI that uses concocted criminal accusations to try to skew a presidential election is a menace to democracy. Reversal of the lower court’s decision is necessary to restore accountability for the kinds of unlawful surveillance and explicit election interference engaged in by the FBI officials here. These powers should never be used against any candidate – whether establishment or populist, left or right. “Reversal of the lower court is also necessary to restore the nation’s trust in intelligence gathering. It is astounding that the same intelligence community that tells Congress to reauthorize FISA’s Section 702 without reforms also waves away the Carter Page scandal, telling us, ‘nothing to see here, folks.’ If Congress reauthorizes Section 702, it should also reform that surveillance program as well as those that were abused to harm Dr. Page. The health of our democracy is at stake.” Case Involves “Unmasking” and “Upstreaming” of 48 Members of Congress Earlier this week, PPSA asked the D.C. Circuit court to require federal agencies to follow FOIA’s most basic requirement: conduct a search for records. Although that should be simple enough, agencies have been excusing themselves of that obligation at an alarming rate, and PPSA has asked the court to rein in this practice.

PPSA’s request this week for an en banc hearing follows up on a FOIA request PPSA submitted in 2020 to six agencies – the Department of Justice and the FBI, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the National Security Agency, the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Department of State. PPSA sought records from these agencies about the possible surveillance of 48 Members of Congress who serve or served on intelligence oversight committees. The request specifically concerns two intelligence practices under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). One such practice is “unmasking,” which results in the naming of Americans caught up in foreign surveillance in U.S. intelligence summaries. The other practice is “upstreaming,” the use of a person’s name as a search term in a database. Targets include prominent current and former House and Senate Members, including Sen. Marco Rubio, Rep. Mike Turner, Rep. Adam Schiff, as well as now-Vice President Kamala Harris and former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. “Their silence speaks volumes,” Gene Schaerr, PPSA general counsel said at the time. “They clearly do not want to answer our requests.” Last year, the district court invoked the judicially created Glomar doctrine, which allows agencies to neither confirm nor deny the existence of records relating to matters critical to national security. In doing so, the district court relied on the D.C. Circuit’s expansion of the Glomar doctrine in Wolf v. CIA (2007) and Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) v. NSA (2012), which allows agencies to refuse to confirm or deny the existence of records without even searching first to determine if any records might exist. In both instances, the federal court allowed the government to skip the search requirement in the text of the Freedom of Information Act. PPSA is now petitioning the court to reconsider this ruling with an en banc hearing with the court. “FOIA’s plain text requires federal agencies to search for responsive records before determining what information they may properly withhold, even in the Glomar context,” PPSA declares. “Wolf and EPIC are untenable in the face of intervening Supreme Court precedent, and they clash with at least three other circuits that, even in Glomar cases, reject deviating from the demands of FOIA’s plain text.” In short, PPSA is alerting this federal court how far it has strayed from precedent and the law. Glomar began as a judicial solution to protect the most sensitive secrets of the nation. In the original case, Glomar protected secrets involving the CIA’s raising of a sunken Soviet nuclear submarine. It has since been expanded to prevent the searching of records; an inherently absurd proposition given that agencies cannot even make a Glomar determination without looking. And Glomar is now reflexively used to plainly defy FOIA, a law that mandates searches. PPSA will report on the court’s response. For years PPSA has documented the increasing disposition of federal intelligence and law enforcement agencies to use the ever-expanding Glomar response – a “cannot confirm or deny” answer once reserved for the nation’s most closely guarded secrets – as a blanket response to any meddlesome Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests.

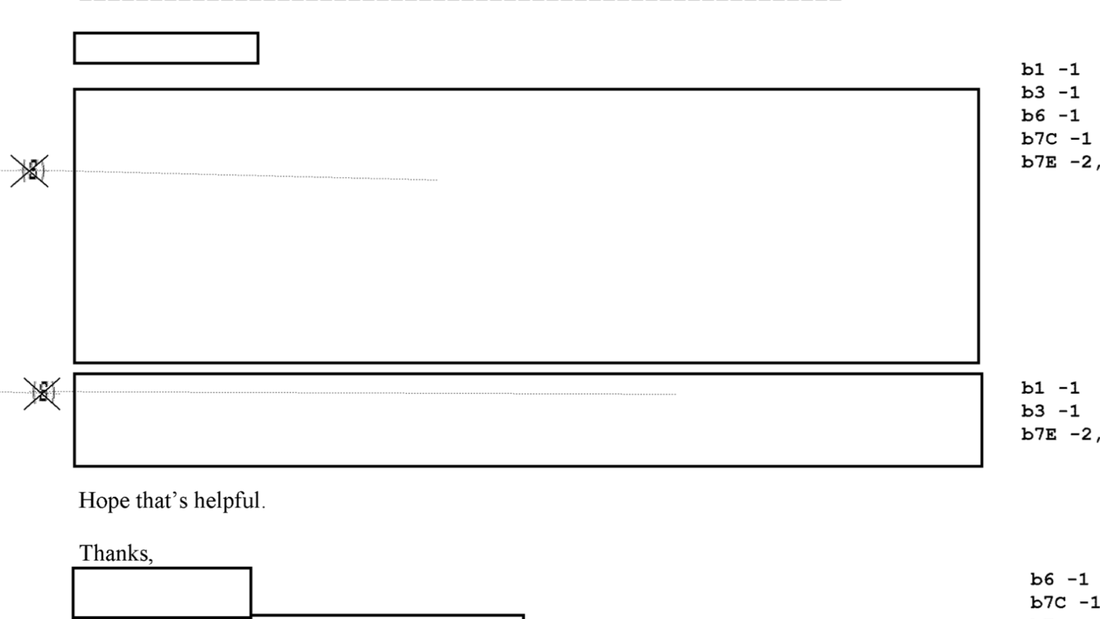

We should not overlook, however, another handy tool for FOIA avoidance, and that is to release the requested document but redact many or all of its meaningful parts. Now the Department of Justice Office of the General Counsel has perfected this technique, taking it to its logical end. It began in 2020 when PPSA joined with Demand Progress to file a FOIA request. Our request concerned surveillance that may be taking place under no statute, but instead under a self-professed authority of the executive branch known as Executive Order 12333. The reply from the FBI is, in its own way, telling. In the DOJ response, a certain Mr. or Ms. BLANK who holds the title of BLANK in the Office of the General Counsel returned with 40 pages of responsive documents. Thirty-nine pages are redacted in their entirety, as is the 40th page, with the redacted name of the signator and his/her redacted title, but with one, unredacted statement: Hope that’s helpful. There’s honestly no other way to take this than the Department of Justice shooting a middle finger at the very idea of a FOIA request, an exercise of the Freedom of Information Act, passed by Congress and signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson. This is a shame because the subject of this request is an important one. Demand Progress and PPSA based our FOIA request on a July 2020 letter from now-retired Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-VT) and current Sen. Mike Lee (R-UT) to then-Attorney General William Barr and then-Director of National Intelligence John Ratcliffe. The two senators noted the expiration of Section 215 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), commonly known as the “business records” provision of FISA. The intelligence community had vociferously lobbied for the renewal of Section 215 with predictions that allowing its expiration would lead to something akin to the city-destroying scenes in the 1996 movie Independence Day. Then the Trump Administration called their bluff and allowed this authority to expire. The response from the intelligence community? Crickets. The sudden complacency of the intelligence community struck many as suspicious. Were federal intelligence and law enforcement agencies shifting their surveillance to another authority? Sens. Leahy and Lee seemed to think so. They wrote: “At times the executive branch has tenuously relied on Executive Order 12333, issued in 1981, to conduct surveillance operations wholly independent of any statutory authorization … This would constitute a system of surveillance with no congressional oversight potentially resulting in programmatic Fourth Amendment violations at tremendous scale … We strongly believe that such reliance on Executive Order 12333 would be plainly illegal.” This July 2020 letter, with a detailed series of penetrating questions about the practice and scope of 12333 surveillance, was issued by two powerful and respected members of the United States Senate … And it hit the walls of the Department of Justice and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence with all the full force of wet spaghetti. As with so many other congressional requests, this letter was not answered in any substantive way. So Demand Progress joined with PPSA in October 2020, in an effort to use the law to compel an answer, this time as a formal FOIA request. We leveraged that law to request responsive documents that would reveal how the agencies might be repurposing EO 12333 to pick up the slack from the expired 215 authority, in order to spy on persons inside the United States. And this is the answer we get. It can only be taken, in a general way, as confirmation that Executive Order 12333 is, in fact, being relied upon for the surveillance of people in the United States. This is one more reason why Congress should use the reauthorization of Section 702 to seek broad surveillance reform, including significant guardrails on Executive Order 12333. With mounting evidence of abuses of Americans’ civil rights, a powerful coalition of leading conservatives and liberals in Congress is building steam to do just that. Hope that’s helpful. Gene Schaerr, PPSA general counsel, today announced the filing of an administrative appeal with the Department of Justice after a “ludicrous scavenger hunt response” from the FBI to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request.

PPSA had submitted this FOIA request in mid-June asking for documents from DOJ law enforcement agencies. PPSA sought records about the use of administrative subpoenas, which are often used to collect bulk data rather than aim at an identifiable target for a specific reason, as required by the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. These subpoenas are often used without any showing of probable case. To learn more about this practice, PPSA requested documents concerning when DOJ uses administrative subpoenas, “whether and when it has used them without probable cause, when it has used them as alternatives to a court-ordered subpoena, and when DOJ shares data obtained through administrative subpoenas with other federal or state agencies.” But the FBI couldn’t trouble itself to search for any records. Instead, the FBI blithely directed PPSA to rummage through the voluminous documents on its online “Search Vault,” suggesting that there could be responsive records somewhere in that database. The FBI never suggested that all responsive records would be found in the Vault. “The FBI’s scavenger hunt response is ludicrous,” Schaerr said. “PPSA sought records reflecting the FBI’s use of administrative subpoenas with and without probable cause. In both instances, the request did not require the FBI to do anything other than search for records concerning the use of administrative subpoenas, and how those subpoenas addressed the presence or absence of probable cause.” Schaerr cited a precedent, Miller v. Casey (1984), that the FBI is bound to read a FOIA request as drafted, not as agency officials might wish it was drafted. “The FBI’s willful refusal to search is a legal error,” Schaerr said. “The FBI might want to avoid the work FOIA requires of it, but we are hopeful the Director of Information Policy at DOJ, and beyond that if necessary, the courts, will recognize that the law does not recognize exceptions for inconvenience.” PPSA awaits responses from other DOJ components, ranging from the Executive Office for United States Attorneys, DOJ’s Criminal Division, the Drug Enforcement Administration, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. PPSA is asking a DC federal court to compel the top federal intelligence and law enforcement agencies to search for records related to how they acquire and use the private, personal information of 110 Members of Congress purchased from third-party data brokers.

In a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request filed in July, 2021, PPSA had asked the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the National Security Agency, the Department of Justice and the FBI, and the CIA for records related to the possible purchase and use of commercially available information on current and former members of the House and Senate Judiciary Committees. The request covered such leading Members of Congress as House Judiciary Chairman Jim Jordan, Ranking Member Jerry Nadler, Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Dick Durbin, Ranking Member Chuck Grassley, and former Members that included Vice President Kamala Harris and Florida Governor Ron DeSantis. PPSA’s motion for summary judgment filed before the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia confronts the assertion by these multiple agencies that to even search for responsive documents would harm national security. PPSA’s motion notes that under FOIA, “agencies must acknowledge the existence of information responsive to a FOIA request and provide specific, non-conclusory justifications for withholding that information.” The agencies instead stonewalled this FOIA request by invoking the judge-created Glomar response, meant to be a rare exception to the general rule of disclosure, which allows the government to neither confirm nor deny the existence of such records. “Requiring Defendants here to perform FOIA searches within the secrecy of their own silos does not, by itself, compel the automatic disclosure of any information whatsoever," PPSA declares in its motion. “[B]ecause the initial step of conducting an inter-agency search makes no such disclosure, their arguments are neither logical nor plausible justifications for shirking their duty to perform an internal search.” The issue of government spying into the private, personal information of Members of Congress, tasked with oversight of these agencies, involve the serious potential for executive intimidation of the legislative branch. The ODNI recently declassified an internal document noting that commercially available information can be used to “facilitate blackmail, stalking, harassment, and public shaming.” “The government doesn’t even want to entertain our question,” said Gene Schaerr, PPSA general counsel. “What do they have to hide?” |

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed