|

PPSA has fired off a succession of Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to leading federal law enforcement and intelligence agencies. These FOIAs seek critical details about the government’s purchasing of Americans’ most sensitive and personal data scraped from apps and sold by data brokers.

PPSA’s FOIA requests were sent to the Department of Justice and the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security, the CIA, the Defense Intelligence Agency, the National Security Agency, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, asking these agencies to reveal the broad outlines of how they collect highly private information of Americans. These digital traces purchased by the government reveal Americans’ familial, romantic, professional, religious, and political associations. This practice is often called the “data broker loophole” because it allows the government to bypass the usual judicial oversight and Fourth Amendment warrant requirement for obtaining personal information. “Every American should be deeply concerned about the extent to which U.S. law enforcement and intelligence agencies are collecting the details of Americans’ personal lives,” said Gene Schaerr, PPSA general counsel. “This collection happens without individuals’ knowledge, without probable cause, and without significant judicial oversight. The information collected is often detailed, extensive, and easily compiled, posing an immense threat to the personal privacy of every citizen.” To shed light on these practices, PPSA is requesting these agencies produce records concerning:

Shortly after the House passed the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, which would require the government to obtain probable cause warrants before collecting Americans’ personal data, Avril Haines, Director of National Intelligence, ordered all 18 intelligence agencies to devise safeguards “tailored to the sensitivity of the information.” She also directed them to produce an annual report on how each agency uses such data. PPSA believes that revealing, in broad categories, the size, scope, sources, and types of data collected by agencies, would be a good first step in Director Haines’ effort to provide more transparency on data purchases. For the second time, PPSA has been forced to go to court to oppose the delaying tactics of the National Security Agency, the CIA, the FBI, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence in complying with its obligations under Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

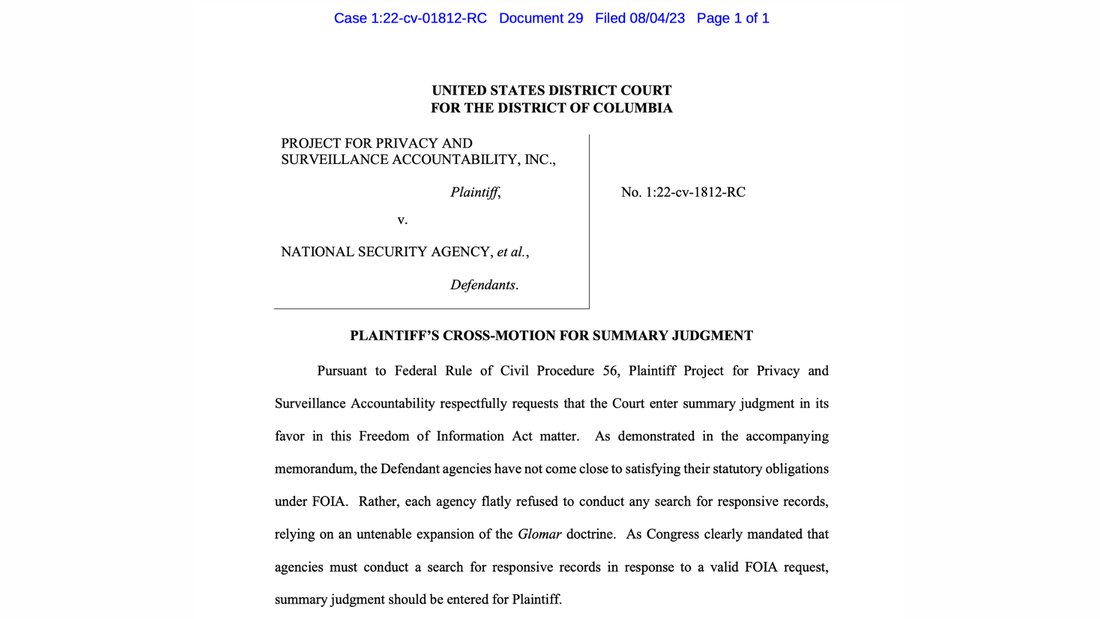

PPSA’s FOIA request, now years old, asks these agencies to produce documents concerning their acquisition and use of commercially available information regarding 145 current and former Members of Congress. These Members have served on committees with oversight responsibilities of the intelligence community. Earlier this year, federal Judge Rudolph Contreras rejected the agencies’ insistence that the Glomar doctrine – which allows agencies to neither confirm nor deny the existence of certain records – relieves them of their statutory obligations to search for responsive records. Judge Contreras had narrowed PPSA’s request to exclude operational documents, ordering agencies to search for only policy documents. He cited agencies correspondence with Members of Congress as an example of a policy document. Judge Contreras wrote, “it is difficult to see how a document such as this would reveal sensitive information about Defendants’ intelligence activities, sources or methods.” Yet the intelligence community is defying its legal obligations for a second time. The agencies’ new strategy rests on a nonsensical linkage to an entirely different PPSA case, currently before the D.C. Circuit, that happens to also use the term “policy documents.” By conflating separate cases, the agencies suggest that they meant to challenge Judge Contreras’ order to search only for “policy documents.” But the agencies have not done so, and this is clearly just the latest delay tactic used to ignore FOIA’s clear search requirement, which Judge Contreras reinforced earlier this year. As a result of this new attempt at delay and obfuscation, agencies are now asking the Court to significantly expand Defendants’ delays by staying this case into 2025. PPSA is hopeful that these agencies will eventually comply with a direct and unambiguous order from a federal judge. The Drug Enforcement Administration’s response to three PPSA Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests shows just how far government respect for that law has fallen. As we’ve seen recently with other government agencies, DEA didn’t even try to pretend it was following that law.

Over the course of a year, PPSA filed three FOIA requests with the DEA seeking documents relating to the use of cell-site simulators, commonly known by the trade name Stingray. Government agencies use these devices to mimic cell towers, pinging consumers’ cellphones in a given geographic area to prompt them to give up private location data, and sometimes the content of communications. PPSA sought records since 2015 that reflect each use of a cell-site simulator by DEA that was conducted without a warrant based on emergency, exceptional, or “exigent” circumstances. We thought it would be a useful guide for public policy to know how often the agency defined something as an emergency, side-stepping the need to obtain a probable cause warrant. On Monday, DEA came back with one combined response to all three FOIAs we had issued over the course of many months. If DEA had followed the law, it would have conformed to a federal precedent, Truitt v. Department of State (1990), which held that it “is elementary that an agency responding to a FOIA request must conduct a search reasonably calculated to uncover all relevant documents, and if challenged, must demonstrate beyond material doubt that the search was reasonable.” Instead, DEA did not even try to pass the laugh test. It waved away all three FOIA requests citing an exemption that covers personnel documents and other Human Relations files. How could PPSA’s request for the use of cell-site simulators for emergency circumstances, in the words of the law, fall under an exemption for subjects that relates “solely to the internal personnel rules and practices of an agency”? In a letter to the Director of Information Policy of the Department of Justice, PPSA general counsel Gene Schaerr responded: “It is almost certain that at least some documents concerning broader surveillance policy or related record-keeping would be responsive. Of course, DEA does not know one way or the other whether this is accurate because it refused to look for responsive records.” How would DEA know that this request only involved personnel records without a responsive search? It is clear that DEA simply wanted to clear this one FOIA request off its desk. We wish this case was an exception. Federal FOIA responses are becoming increasingly farcical. A FOIA response from the Department of Justice included 40 redacted pages with an insulting valediction – “hope that’s helpful.” Expect this lawless attitude toward the Freedom of Information Act to continue until courts step in and start leveling sanctions against those who treat the law as an ignorable suggestion. Agencies Must Release Policy Documents About Purchase of the Personal Data of 145 Members of Congress Late last week, Judge Rudolph Contreras ordered the NSA, the CIA, the FBI, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence to respond to a PPSA Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. The government now has two weeks to schedule the production of “policy documents” regarding the intelligence community’s acquisition and use of commercially available information regarding 145 current and former Members of Congress.

This is the second time Judge Contreras has had to tell federal agencies to respond to a FOIA request PPSA submitted. In late 2022, Judge Contreras rejected in part the FBI’s insistence that the Glomar doctrine allowed it to ignore FOIA’s requirement to search for responsive records. Despite that clear holding, the FBI – joined this time by several other agencies – again refused to search for records in response to PPSA’s FOIA request. And Judge Contreras had to remind the agencies again that FOIA’s search obligations cannot be ducked so easily. Instead, Judge Contreras found that PPSA “logically and plausibly” requested the policy documents about the acquisition of commercially available information. And Judge Contreras concluded that a blanket Glomar response, in which the government neither confirms nor denies the existence of the requested documents, is appropriate only when a Glomar response is justified for all categories of responsive records. The judge then described a hypothetical letter from a Member of Congress to the NSA that clarifies the distinction between operational and policy documents. He considered that such a letter might ask if the NSA “had purchased commercially available information on any of the listed Senators or Congresspeople” without revealing whether the NSA (or any other of the defendant agencies) “had a particular interest in surveilling the individual.” Judge Contreras decided that “it is difficult to see how a document such as this would reveal sensitive information about Defendants’ intelligence activities, sources, or methods.” It is on this reasoning that the judge ordered these agencies to produce these policies documents. We eagerly awaits the delivery of these documents in both cases. Stay tuned. Case Involves “Unmasking” and “Upstreaming” of 48 Members of Congress Earlier this week, PPSA asked the D.C. Circuit court to require federal agencies to follow FOIA’s most basic requirement: conduct a search for records. Although that should be simple enough, agencies have been excusing themselves of that obligation at an alarming rate, and PPSA has asked the court to rein in this practice.

PPSA’s request this week for an en banc hearing follows up on a FOIA request PPSA submitted in 2020 to six agencies – the Department of Justice and the FBI, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the National Security Agency, the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Department of State. PPSA sought records from these agencies about the possible surveillance of 48 Members of Congress who serve or served on intelligence oversight committees. The request specifically concerns two intelligence practices under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). One such practice is “unmasking,” which results in the naming of Americans caught up in foreign surveillance in U.S. intelligence summaries. The other practice is “upstreaming,” the use of a person’s name as a search term in a database. Targets include prominent current and former House and Senate Members, including Sen. Marco Rubio, Rep. Mike Turner, Rep. Adam Schiff, as well as now-Vice President Kamala Harris and former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. “Their silence speaks volumes,” Gene Schaerr, PPSA general counsel said at the time. “They clearly do not want to answer our requests.” Last year, the district court invoked the judicially created Glomar doctrine, which allows agencies to neither confirm nor deny the existence of records relating to matters critical to national security. In doing so, the district court relied on the D.C. Circuit’s expansion of the Glomar doctrine in Wolf v. CIA (2007) and Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) v. NSA (2012), which allows agencies to refuse to confirm or deny the existence of records without even searching first to determine if any records might exist. In both instances, the federal court allowed the government to skip the search requirement in the text of the Freedom of Information Act. PPSA is now petitioning the court to reconsider this ruling with an en banc hearing with the court. “FOIA’s plain text requires federal agencies to search for responsive records before determining what information they may properly withhold, even in the Glomar context,” PPSA declares. “Wolf and EPIC are untenable in the face of intervening Supreme Court precedent, and they clash with at least three other circuits that, even in Glomar cases, reject deviating from the demands of FOIA’s plain text.” In short, PPSA is alerting this federal court how far it has strayed from precedent and the law. Glomar began as a judicial solution to protect the most sensitive secrets of the nation. In the original case, Glomar protected secrets involving the CIA’s raising of a sunken Soviet nuclear submarine. It has since been expanded to prevent the searching of records; an inherently absurd proposition given that agencies cannot even make a Glomar determination without looking. And Glomar is now reflexively used to plainly defy FOIA, a law that mandates searches. PPSA will report on the court’s response. For years PPSA has documented the increasing disposition of federal intelligence and law enforcement agencies to use the ever-expanding Glomar response – a “cannot confirm or deny” answer once reserved for the nation’s most closely guarded secrets – as a blanket response to any meddlesome Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests.

We should not overlook, however, another handy tool for FOIA avoidance, and that is to release the requested document but redact many or all of its meaningful parts. Now the Department of Justice Office of the General Counsel has perfected this technique, taking it to its logical end. It began in 2020 when PPSA joined with Demand Progress to file a FOIA request. Our request concerned surveillance that may be taking place under no statute, but instead under a self-professed authority of the executive branch known as Executive Order 12333. The reply from the FBI is, in its own way, telling. In the DOJ response, a certain Mr. or Ms. BLANK who holds the title of BLANK in the Office of the General Counsel returned with 40 pages of responsive documents. Thirty-nine pages are redacted in their entirety, as is the 40th page, with the redacted name of the signator and his/her redacted title, but with one, unredacted statement: Hope that’s helpful. There’s honestly no other way to take this than the Department of Justice shooting a middle finger at the very idea of a FOIA request, an exercise of the Freedom of Information Act, passed by Congress and signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson. This is a shame because the subject of this request is an important one. Demand Progress and PPSA based our FOIA request on a July 2020 letter from now-retired Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-VT) and current Sen. Mike Lee (R-UT) to then-Attorney General William Barr and then-Director of National Intelligence John Ratcliffe. The two senators noted the expiration of Section 215 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), commonly known as the “business records” provision of FISA. The intelligence community had vociferously lobbied for the renewal of Section 215 with predictions that allowing its expiration would lead to something akin to the city-destroying scenes in the 1996 movie Independence Day. Then the Trump Administration called their bluff and allowed this authority to expire. The response from the intelligence community? Crickets. The sudden complacency of the intelligence community struck many as suspicious. Were federal intelligence and law enforcement agencies shifting their surveillance to another authority? Sens. Leahy and Lee seemed to think so. They wrote: “At times the executive branch has tenuously relied on Executive Order 12333, issued in 1981, to conduct surveillance operations wholly independent of any statutory authorization … This would constitute a system of surveillance with no congressional oversight potentially resulting in programmatic Fourth Amendment violations at tremendous scale … We strongly believe that such reliance on Executive Order 12333 would be plainly illegal.” This July 2020 letter, with a detailed series of penetrating questions about the practice and scope of 12333 surveillance, was issued by two powerful and respected members of the United States Senate … And it hit the walls of the Department of Justice and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence with all the full force of wet spaghetti. As with so many other congressional requests, this letter was not answered in any substantive way. So Demand Progress joined with PPSA in October 2020, in an effort to use the law to compel an answer, this time as a formal FOIA request. We leveraged that law to request responsive documents that would reveal how the agencies might be repurposing EO 12333 to pick up the slack from the expired 215 authority, in order to spy on persons inside the United States. And this is the answer we get. It can only be taken, in a general way, as confirmation that Executive Order 12333 is, in fact, being relied upon for the surveillance of people in the United States. This is one more reason why Congress should use the reauthorization of Section 702 to seek broad surveillance reform, including significant guardrails on Executive Order 12333. With mounting evidence of abuses of Americans’ civil rights, a powerful coalition of leading conservatives and liberals in Congress is building steam to do just that. Hope that’s helpful. Gene Schaerr, PPSA general counsel, today announced the filing of an administrative appeal with the Department of Justice after a “ludicrous scavenger hunt response” from the FBI to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request.

PPSA had submitted this FOIA request in mid-June asking for documents from DOJ law enforcement agencies. PPSA sought records about the use of administrative subpoenas, which are often used to collect bulk data rather than aim at an identifiable target for a specific reason, as required by the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. These subpoenas are often used without any showing of probable case. To learn more about this practice, PPSA requested documents concerning when DOJ uses administrative subpoenas, “whether and when it has used them without probable cause, when it has used them as alternatives to a court-ordered subpoena, and when DOJ shares data obtained through administrative subpoenas with other federal or state agencies.” But the FBI couldn’t trouble itself to search for any records. Instead, the FBI blithely directed PPSA to rummage through the voluminous documents on its online “Search Vault,” suggesting that there could be responsive records somewhere in that database. The FBI never suggested that all responsive records would be found in the Vault. “The FBI’s scavenger hunt response is ludicrous,” Schaerr said. “PPSA sought records reflecting the FBI’s use of administrative subpoenas with and without probable cause. In both instances, the request did not require the FBI to do anything other than search for records concerning the use of administrative subpoenas, and how those subpoenas addressed the presence or absence of probable cause.” Schaerr cited a precedent, Miller v. Casey (1984), that the FBI is bound to read a FOIA request as drafted, not as agency officials might wish it was drafted. “The FBI’s willful refusal to search is a legal error,” Schaerr said. “The FBI might want to avoid the work FOIA requires of it, but we are hopeful the Director of Information Policy at DOJ, and beyond that if necessary, the courts, will recognize that the law does not recognize exceptions for inconvenience.” PPSA awaits responses from other DOJ components, ranging from the Executive Office for United States Attorneys, DOJ’s Criminal Division, the Drug Enforcement Administration, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. PPSA is asking a DC federal court to compel the top federal intelligence and law enforcement agencies to search for records related to how they acquire and use the private, personal information of 110 Members of Congress purchased from third-party data brokers.

In a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request filed in July, 2021, PPSA had asked the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the National Security Agency, the Department of Justice and the FBI, and the CIA for records related to the possible purchase and use of commercially available information on current and former members of the House and Senate Judiciary Committees. The request covered such leading Members of Congress as House Judiciary Chairman Jim Jordan, Ranking Member Jerry Nadler, Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Dick Durbin, Ranking Member Chuck Grassley, and former Members that included Vice President Kamala Harris and Florida Governor Ron DeSantis. PPSA’s motion for summary judgment filed before the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia confronts the assertion by these multiple agencies that to even search for responsive documents would harm national security. PPSA’s motion notes that under FOIA, “agencies must acknowledge the existence of information responsive to a FOIA request and provide specific, non-conclusory justifications for withholding that information.” The agencies instead stonewalled this FOIA request by invoking the judge-created Glomar response, meant to be a rare exception to the general rule of disclosure, which allows the government to neither confirm nor deny the existence of such records. “Requiring Defendants here to perform FOIA searches within the secrecy of their own silos does not, by itself, compel the automatic disclosure of any information whatsoever," PPSA declares in its motion. “[B]ecause the initial step of conducting an inter-agency search makes no such disclosure, their arguments are neither logical nor plausible justifications for shirking their duty to perform an internal search.” The issue of government spying into the private, personal information of Members of Congress, tasked with oversight of these agencies, involve the serious potential for executive intimidation of the legislative branch. The ODNI recently declassified an internal document noting that commercially available information can be used to “facilitate blackmail, stalking, harassment, and public shaming.” “The government doesn’t even want to entertain our question,” said Gene Schaerr, PPSA general counsel. “What do they have to hide?” One of the frustrations – there are many – of trying to pry answers about surveillance policy from federal agencies with Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests are the heavy redactions to responsive documents that protect “sources and methods.”

No one wants to blow a technique by which government intelligence and law enforcement agencies track bad guys. And no one wants an undercover agent or a confidential informant to wind up tied to a chair in dank basement because their cover was blown. And so when redactions come back with heavy ink, we are supposed to trust that the government has good reasons for holding back that information. According to an Executive Order issued by President Obama, EO 13526, information cannot be classified by the government to merely spare an agency embarrassment. Enter Paul Sperry of RealClear Investigations, who brings to light a new twist in a saga that we thought had been thoroughly explored – the problems with the FBI’s four applications to surveil Trump campaign advisor Carter Page in 2016 and 2017. Sperry reports that redactions in a “Classified Appendix” to Special Counsel John Durham’s final report have nothing to do with sources and methods. It concerns an FBI request to the secret FISA Court to allow the Bureau to continue spying on Carter Page in early 2017. The FBI indicated that it had verified a rumor that Page had worked with the Kremlin to swing the recent election in Trump’s favor. When the black ink is stripped away, Sperry reports, what did the redactions hide? They disguised the fact that the FBI took this investigative lead from a news story in The Washington Post, which the newspaper later retracted after determining it to be false. So that’s the FBI’s “source and method” deemed so sensitive that it had to be hidden from the public? It was a subscription to The Washington Post. Who knows what other embarrassments government hides with its redactions. When all else fails, the government can simply refuse to respond at all by issuing a Glomar response. This is a court-created doctrine that came out of a super-secret CIA project to refloat a sunken Soviet submarine. Ever since, the Glomar response has been used to protect information so sensitive that the government is allowed to neither confirm nor deny… anything. So forgive us if we’re jaded enough to believe that much of the black ink and Glomar responses are just the government protecting its own backside. “Fruit of a Poisonous Tree”FBI documents acquired through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests by PPSA and the American Civil Liberties Union show how authorities continue to conceal information about how stingray technology is really being used. The downstream effect of this deception likely results in defendants being denied the ability to know how a case was constructed against them, degrading their right to a fair trial.

Dozens of federal and state agencies have benefitted from the generosity of the Department of Justice in sharing with state and local police cell-site simulators, popularly known by the brand name “Stingrays.” These devices trick cellphones into revealing their owners’ locations and other sensitive, personal information. An email from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), released today by PPSA, one ATF official writes to another: “To remain consistent with our DOJ Partner, in this case, the USMS (U.S. Marshall Service) since they are the largest user of this technology, we respectfully request that this technique not be disclosed in an affidavit.” ACLU’s FOIA shows the same instructions from the federal government imposed in nondisclosure agreements on police departments when they ask for this technology to track suspects. These contracts don’t beat around the bush. They explicitly require police departments to withhold information about stingrays and their usage from defendants and lawyers. The FBI argues that such secrecy is required to prevent revealing information that would enable criminals to “thwart law enforcement efforts.” But what’s the big secret? Despite the clandestine nature of this federal/local partnership program, stingray technology and its capabilities have been an open secret for years now. This technology was depicted under another brand name – “triggerfish” –on season three of HBO’s The Wire. That was in 2004. Could the real secret be that police departments are conspiring with the FBI to conceal the use of privacy-invading technology to give prosecutors an unfair, “backdoor” advantage in their cases? PPSA has often reported the ways in which federal or state agencies routinely circumvent constitutional privacy protections. One well-known method is the parallel construction of evidence, in which prosecutors leverage illicitly gained knowledge to turn up evidence from a source acceptable in court. It is well established legal doctrine that illicit evidence, the “fruit of the poisonous tree,” should not be admissible. But who knows what is poisonous if the tree is hidden? The acquired federal documents actually spell out how parallel construction should work – advising the police to pursue “additional and independent investigative means and methods” to obtain evidence collected through use of a cell-site simulator. The suggestions on how to accomplish such secrecy were redacted by the FBI. The Bureau argues that revealing information about stingrays would have a “significant detrimental impact on the national security of the United States.” The revelation of even minor details is so heavily restricted that police have dropped charges against a suspect rather than unveil information in open court. “The important question posed by privacy advocates is why are police departments and the FBI going to such lengths to conceal information about a technology that is public knowledge?” asked Bob Goodlatte, former chairman of the House Judiciary Committee and PPSA Senior Policy Advisor. “The capabilities of stingrays are well-known, with knowledge of their deployment on popular television almost twenty years ago. “Yet the government still insists that the basics of stingray use is a precious national secret,” Goodlatte said. “Congress should demand to know if there is any basis at all for these non-disclosure agreements – and how common parallel construction really is in practice.” In 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court held that a warrant is needed before government agencies can seize your location history from cell-site records. That opinion, Carpenter v. United States, often described as a landmark ruling, has actually become little more than a legal watermark thanks to the machinations of government agencies.

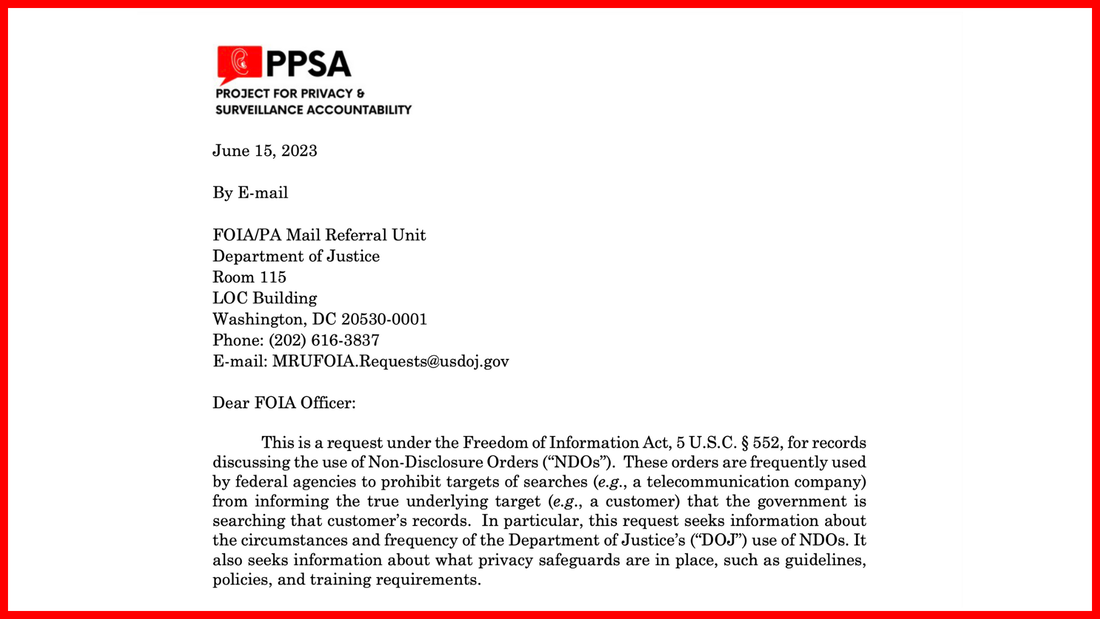

When a government agency wants to know where you’ve been, or anything about you, all it has to do is consult the trove of sensitive personal information on millions of Americans scraped from apps and purchased from third-party data brokers. No warrants required. As they used to say in internet ads, the government knows all about you with this one weird trick. Two responses to PPSA Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests show how freely the FBI and DIA access Americans’ personal information. The FBI has a team dedicated to working with cell tower data. Their specialties include “historical CDR (call detail records) analysis and geospatial mapping,” which enables the tracking of people across multiple towers. The FBI conducts “tower dump analysis,” which seems to be the collection of bulk data from cell towers and “real-time cellular tracking” services. The documents obtained by PPSA show that the FBI regularly lends out these services to state and local governments. The Defense Intelligence Agency documents show that the agency uses commercially available data for “cover operations.” Does this mean DIA is using data to help agents impersonate real people? Or is DIA using our personal information as material from which to create fake, chimeric identities, using a blend of personal information from multiple real people? These are just glimpses into how the government uses our personal information, from our movements to our personal interests, relationships, and beliefs. PPSA will continue to use FOIAs and lawsuits to dig out more details about these practices. PPSA today announces the submittal of a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request with the Department of Justice seeking records on how and when DOJ uses secretive non-disclosure orders, or NDOs. Through such orders, DOJ is able to obtain private information from internet and telecom companies while also prohibiting those companies from informing American consumers that their personal information has been searched by the government.

In June, the House passed the NDO Fairness Act by voice vote. If enacted, this legislation would restrain the government practice of issuing NDOs to internet and telecom companies. While the Senate prepares to take up this legislation, PPSA thought it would be useful to inform the debate with information on the circumstances and frequency with which the Department of Justice and its agencies issue NDOs. We also thought it would be useful for senators to know what privacy safeguards are in place, including government guidelines, policies, and training requirements. With that in mind, PPSA submitted this FOIA request to the Department of Justice, and its components – the Executive Office for United States Attorneys, the FBI, the Drug Enforcement Administration, DOJ’s Criminal Division, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. We are asking for records concerning:

“We have every reason to expect the government can release this basic data about how many NDOs are issued, the circumstances that prompted them, and the guardrails, if any, that constrain them,” said Gene Schaerr, PPSA general counsel. “We are not asking the government for a favor. We are seeking information Americans should know and the Senate needs for its debate.” PPSA today announced the filing of a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request with the Department of Justice asking for documents and records showing whether DOJ ensures it has probable cause before issuing administrative subpoenas to seize Americans’ private electronic data.

Civil libertarians have long suspected that the DOJ often uses such administrative subpoenas to circumvent the probable-cause requirement for searching Americans’ records. This is particularly troubling, since such subpoenas, issued without a court order or judicial oversight, are often used to collect bulk data rather than targeting information from an identifiable target. “It may be likened to a fishing expedition, with Americans as the fish,” said Gene Schaerr, PPSA general counsel. PPSA’s FOIA request covers all the components of the Department of Justice, including the Executive Office for United States Attorneys, the FBI, the Drug Enforcement Administration, the DOJ’s Criminal Division, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. PPSA is seeking:

“We are not asking about sources or methods or anything else that would trigger a Glomar response that would shut off all disclosure,” Schaerr said. “We seek topline information necessary for Congress to conduct oversight and for the American people to understand how our government uses our most personal and sensitive information.” John Greenwald at The Black Vault reports a curious change in the responsiveness of the National Security Agency to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests regarding Intellipedia, a shared source within the intelligence community.

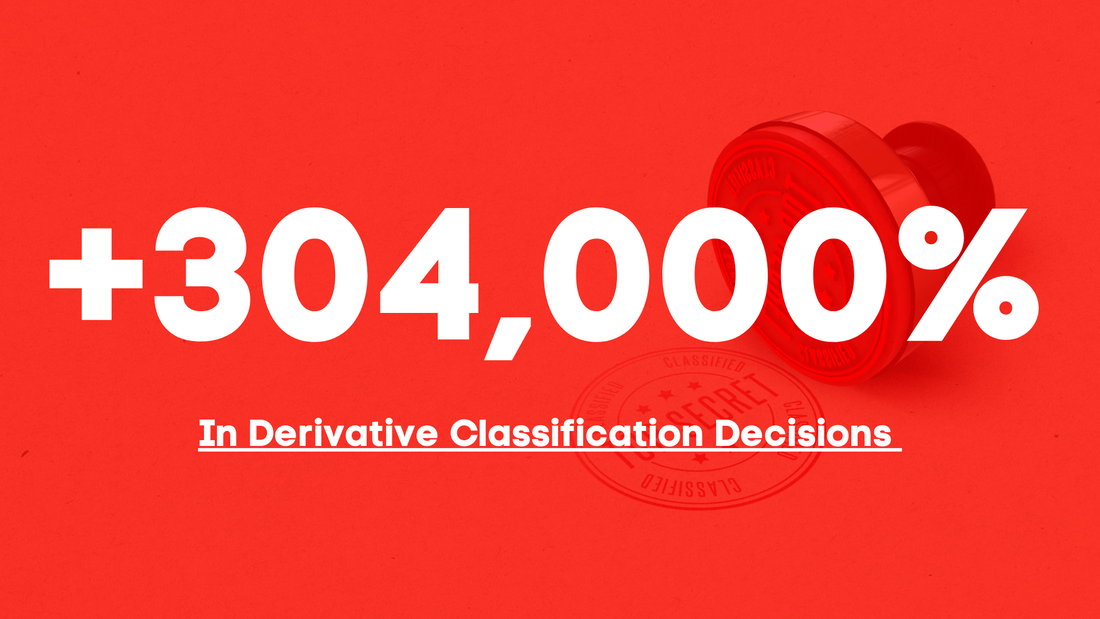

This online system gives the intelligence community a collaborative way to share information, insights, and theories across agencies, breaking down many of the barriers that restricted sharing of intel pre-9/11. Intellipedia consists of wikis that contain “Top Secret Sensitive Compartmented Information,” “Secret Information,” and “Sensitive But Unclassified Information.” Think of it as Wikipedia for spies. For years, NSA had routinely released articles and category pages that reside in this digital resource. The Black Vault filed FOIA requests with NSA – which handles such requests for Intellipedia – to obtain glimpses into the unclassified collaborative thinking of the intelligence community. Greenwald writes that in 2017, a successful FOIA appeal revealed that Intellipedia had more than 50,000 content pages in the unclassified section; more than 114,000 content pages in the “Secret” section; and more than 124,000 pages in the “Top Secret” section. It also included, he writes, “millions of additional pages within those three systems that includes other wiki pages, talk pages, and redirects, and finally, the three systems hold more than 600,000 uploaded files for download.” He postulates that these numbers are likely much larger five years later, a reasonable guess considering the swelling numbers of classified documents across government. The NSA, despite having released unclassified articles and pages for over a decade, is now issuing the all-too common Glomar response – neither confirming nor denying the existence of requested documents – and turning to statutory exemptions that it failed to invoke for over that ten years. What changed? “This sets a concerning precedent,” Greenwald writes, “as it suggests that government agencies might have the ability to bypass the established FOIA exemptions and deny information requests based on internal policy decisions made on a whim.” In our experience, the evolution of the Glomar response into an all-purpose stonewall is the rule. Intellipedia was a refreshing exception, perhaps a reflection of the creative impulse of the people behind it. Now it’s just like everything else in the government – even with unclassified information, it’s strictly need to know, old chum, and you don’t need to know. In a recent response to a Freedom of Information Act request PPSA submitted in 2020, the National Security Agency released a record showing an exponential – no, make that mind-blowing – increase in the number of “derivative classification” decisions.

In plain English, “derivative classification” describes the decision to classify a document because it incorporates, paraphrases, restates, or generates in new form information that is already classified. Makes sense, right? Now explain this. NSA released forms showing that the number of derivative classification decisions in just that agency increased from approximately 11,500 in 2007-2008, to over 20 million in 2008-2009, and to more than 35 million in 2010. That’s an increase of more than 304,000 percent! And, while recent years have seen a decrease – 23 million in 2013 and 7 million in 2017, these are still eye-popping increases over the 2008 level of 11,544. What might explain this explosive reliance on derivative classification? Perhaps it is a response to President Obama’s Executive Order 13526, which was meant to stem the tide of classified documents and to prevent agencies from classifying documents “for self-serving reasons or simply to avoid embarrassment.” Does the explosive increase in derivative documents decisions represent the bureaucracy’s work-around President Obama’s order? Overtly classified documents grew from 55 million when President Obama issued his order to 77.5 million five years later. Are these newly released numbers evidence the government is using the derivative classification mechanism to enlarge the classified state even more? Yet another good question for Congress to ask. In the meantime, PPSA has recently filed a Freedom of Information Act request asking NSA, as well as the FBI and Office of the Director of Intelligence, to produce documents that would explain wild fluctuations in derivative classification and increases in hiring and software purchases to handle such volumes. We will report any details PPSA receives that might explain this explosive growth of derivative classification. Credit to the Department of Justice for a voluminous response to our Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. Our request concerned the use of stingrays, or cell-site simulators, by that department and its agencies. Out of more than 1,000 pages in DOJ’s response, we’ve found a few gems. Perhaps you can find your own.

Review our digest of this document here, and the source document here. The original FOIA request concerned DOJ policies on cell-site simulators, commonly known by the commercial brand name “stingrays.” These devices mimic cell towers to extract location and other highly personal information from your smartphone. The DOJ FOIA response shows that the FBI in 2021 invested $16.1 million in these cell-site simulators (p. 209) in part to ensure they “are capable of operating against evolving wireless communications.” The bureau also asked for $13 million for “communications intercept resources.” This includes support for the Sensitive Investigations Unit’s work in El Salvador (p. 111). On the policy side, we’ve reported that some federal agencies, such as the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, maintain that stingrays are not GPS location identifiers for people with cellphones. This is technically true. Stingrays do not download location data or function as GPS locators. But this is too clever by half. Included in this release is an Obama-era statement by former Department of Justice official Sally Yates that undermines this federal claim by stating: “Law enforcement agents can use cell-site simulators to help locate cellular devices whose unique identifiers are known …” (p. 17) This release gives an idea of how versatile stingrays have become. The U.S. Marshals Service (p. 977) reveals that it operates cell-site simulators and passive wireless collection sensors to specifically locate devices inside multi-dwelling buildings. Other details sprinkled throughout this release concern other, more exotic forms of domestic surveillance. For example, the U.S. Marshals Service Service has access to seven aircraft located around the country armed with “a unique combination of USMS ELSUR suite, high resolution video surveillance capability … proven to be the most successful law enforcement package” (p.881-883). A surveillance software, “Dark HunTor,” exposes user data from Tor, the browser meant to make searches anonymous, as well as from dark web searches for information. (p. 105) In addition, the U.S. Marshals Service Service “has created the Open-Source Intelligence Unit (OSINT) to proactively review and research social media content. OSINT identifies threats and situations of concern that may be currently undetected through traditional investigative methods. Analyzing public discourse on social media, its spread (‘likes,’ comments, and shares), and the target audience, the USMS can effectively manage its resources appropriate to the identified threats.” (p. 931) The DOJ release also includes details on biometric devices, from facial recognition software to other biometric identifiers, (p.353), as well as more than $10 million for “DNA Capability Expansion” (p.365). Is that all? Feel free to look for yourself. The Project for Privacy and Surveillance Accountability today filed a federal lawsuit against the Department of Justice and the FBI for their failure to make a lawful response to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request for records in relation to opinions issued to the Bureau by two secret courts.

On June 28, PPSA submitted a FOIA request seeking decisions, orders, and opinions from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC), and its superior, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court of Review (FISCR). PPSA also requested agency records concerning regulations, policies, training, and clearance levels for individuals with access to FISC and FISCR opinions. The FBI took two swings at responding to PPSA’s request, missing the ball each time. In its first response, the FBI refused to conduct any searches for court opinions because, it claimed, “the above referenced subject is not searchable” in one particular FBI index – the Central Records System – ignoring the fact that the FBI maintains several other databases for storing records. The FBI simply refused to consider those locations, explaining only that its Central Records System “is not arranged in a manner that allows for the retrieval of information in the form you have requested.” “In other words, the Federal Bureau of Investigation – which submits surveillance warrants for Americans under Title I of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act before FISC – said with a straight face that it cannot locate court opinions that directly concern it,” said Gene Schaerr, general counsel of PPSA. “Even Inspector Clouseau would be embarrassed by a response like that. “Since when does locating easily identifiable records – including judicial decisions the FBI is bound to read and obey as drafted – become such an overwhelming burden?” Schaerr said. “The FBI is being facetious.” In the FBI’s second response, responding to the request for policies governing who within the FBI has access to FISC decisions, the Bureau completely ignored its statutory obligations under FOIA. Although FOIA requires the FBI to search for all responsive records, the FBI stated that it stopped looking for any records after locating the first record – a heavily redacted document, “Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act and Standard Minimization Procedures Policy Guide.” According to the FBI, that “fulfilled” its obligation. Today’s lawsuit that PPSA filed in the U.S. District Court of the District of Columbia demonstrates otherwise. “We hope the court will see that the FBI is treating the FOIA statute as a shell game in which litigants will tire out and leave them alone,” Schaerr said. “We won’t leave them alone. We ask the court to demonstrate to the Bureau that it is unacceptable to ignore even the minimum requirements of the law.” Our government can operate in grey areas of the law because agencies have become adept at exploiting every loophole, exception, or tiny bit of leeway in a statute. PPSA announces today the submission of two Freedom of Information Act requests to the Department of Justice to shed light on practices in two such areas of concern – surveillance of cellphone data by devices that imitate cell towers, and the role of privacy experts in a secret court.

The first FOIA request concerns cell-site simulators that law enforcement agencies use to mimic cell towers, allowing them to snatch location data and other information from the cellphones of people at a given location. These devices, commonly known as “stingrays,” are used to track people by pinging their phones. This digital intrusion is at odds with the spirit of the Supreme Court opinion in Carpenter v. United States, where the Court in 2018 rejected unlimited government access to cellphone location data. But the high Court did not specifically ban cell-site simulators. So, with this tiny distinction, stingrays are still commonly used by 14 federal agencies and police in cities around the country. In 2015, the Department of Justice did produce a memo requiring a warrant for some uses of this technology. That memo, however, allows federal agencies free use of this technology in “exigent” circumstances. How dire does a circumstance have to be to be “exigent”? Virtually everyone agrees that if a child is thrown into a stranger’s car, or a terrorist is known to be planting a bomb, law enforcement should be able to get their hands on stingray data in an instant. But given the slipperiness with which the government defines legal terms, what are the actual circumstances in which stingrays have been used?

In this way, PPSA is seeking to discover if federal agencies are playing fair with the “exigent” exception. PPSA’s second FOIA request concerns the use – or rather, the non-use – of amicus advisors by the FISC. A little history is in order. When Judge James E. Boasberg of the secret court heard requests from the FBI for permission to surveil presidential campaign aide Carter Page, the judge could have sought advice from a privacy lawyer with high-security clearance. Such an amicus could have helped guide the judge through the competing issues in a case fraught with civil liberty concerns, not the least of which were the First Amendment rights of 137.5 million voters. Judge Boasberg demurred. It appears he did not seek an amicus and missed spotting a circus of misdirection and shocking omissions in the FBI’s requests, including submission by an FBI lawyer of a forged document. It is with this in mind that we supported the Leahy-Lee measure in the previous Congress that would bring checks and balances into FISC proceedings. This legislation would bring to the one-sided nature of FISC hearings a privacy-oriented advocate to independently verify the FISA application’s material assertions whenever a case touches on the civil rights of sensitive cases involving political campaigns, federal officials, the practice of journalism, religious minorities, or other sensitive areas. Since this is not the law, PPSA filed this FOIA request.

We would prefer not to have to pull out a legal microscope. But given the disingenuous way our government finds exceptions for lawless acts, we feel they have given us no choice. PPSA will report on any responses. PPSA recently reported that the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), in a response to our Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, downplayed its use of stingrays, as cell-site simulators are commonly called. Yet one agency document revealed that stingrays are “used on almost a daily basis in the field.” This was a critical insight into real-world practice. These cell-site simulators impersonate cell towers to track mobile device users. Stingray technology allows government agencies to collect huge volumes of personal information from many cellphones within a geofenced area. We now have more to report with newly-released documents that, as before, include material for internal training of ATF agents. One of the most interesting findings is not what we can see, but what we can’t see – the parts of documents ATF takes pains to hide. The black ink covers a slide about the parts of the U.S. radio spectrum. Since this is a response to a FOIA request about stingrays, it is likely that the spectrum discussed concerns the frequencies telecom providers use for their cell towers. What appears to be a quotidian training course for agents on electronic communications has the title of the course redacted. If that is so, was there something revealing about the course title that we are not allowed to see? Could it be “Stingrays for Dummies?” The redactions also completely cover eleven pages about pre-mission planning. Do these pages reveal how ATF manages its legal obligations before using stingrays? This course presentation ends somewhat tastelessly, a slide with a picture of a compromised cell-tower disguised as a palm tree. In the release of another tranche of ATF documents, forty-five pages are blacked out. It appears from the preceding email chain that these pages included subpoenas for a warrant executed with the New York Police Department. The document assigns any one of a pool of agents to “swear out” a premade affidavit to support the subpoena. The ATF reveals it uses stingrays on aircraft, which requires a high level of administrative approval. It seems, however, from an ATF PowerPoint presentation that this is a policy change, which suggests that prior approvals were lax. Was this a reaction to the 2015 Department of Justice’s policy on cell-site simulators? If aerial surveillance now requires a search warrant, what was previously required – and how was such surveillance used? Was it used against whole groups of protestors? Finally, the documents reveal that the ATF has had cell-site simulators in use in field divisions in major cities, including Chicago, Denver, Detroit, Houston, Kansas City, Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Tampa, as well as other cities. PPSA will report more on ATF’s ongoing document dumps as they come in. By The Way... Here's How ATF Glosses Over Its Location TrackingThe training manual of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives states that cell-site simulators “do not function as a GPS locator, as they do not obtain or download any location information from the device or its applications.” This claim is disingenuous. It is true that exact latitude and longitude data are not taken. But by tricking a target’s phone into connecting and sending strength of signal data to a cell tower, the cell-site simulator allows the ATF to locate the cellphone user to within a very small area. If a target uses multiple cell-site simulators, agents can deduce his or her movements throughout the day.

Below is an example from a Drug Enforcement Agency document that shows how this technology can be used to locate a target (seen within the black cone) in a small area. The media is aflame with stories about the mishandling of classified material by President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump, with partisans arguing why one or the other is in greater breach of the law. Trevor Timm, executive director of the Freedom of the Press Foundation, looks beyond the partisan wrangling at the underlying problem: the Espionage Act of 1917. Like a deep trawl scraping the ocean floor, the Espionage Act is broad enough to catch almost everything, including the wrong fish.

The Espionage Act is the worst kind of law, one that is as vague as it is broad. It weaponizes the tendency of government to put a “classified” stamp on even anodyne material. “No one is ever punished for overclassifying information, yet plenty of people go to prison for disclosing information to journalists that never should have been classified to begin [with],” Trim wrote in The Guardian. “Even efforts to reform the secrecy system end up being classified themselves.” PPSA filed Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests before a host of government agencies seeking documents that would gauge how well they are complying with an Executive Order 13526. This order, issued by President Obama, was meant to stem the tide of classification and prevent government agents from classifying documents “for self-serving reasons or simply to avoid embarrassment.” In the wake of President Obama’s executive order to curb over-classification, the number of U.S. classified government documents rose from almost 55 million to 77.5 million documents in five years. Less than one percent of federal money spent on the classification system is spent on declassification. “Tens or hundreds of millions of documents are classified per year,” Timm wrote. “A tiny fraction will ever see the light of day, despite the fact the vast majority never should have been given the ‘secret’ stamp in the first place.” While most government agencies have ignored PPSA’s FOIA requests, the State Department did respond to PPSA with a pinhole look at some of the problems with its classification system. Documents were classified when they shouldn’t have been; documents were classified at the wrong level; some information was classified for a longer duration than necessary. The government is self-forgiving, allowing itself to be free to make mistakes, but an American accused under the Espionage Act is apt to get rough treatment and a good stretch in a federal prison. We should remember that the Espionage Act was the centerpiece of the police state erected by President Woodrow Wilson. Socialist Charles T. Schenck went to prison for violating that law. His crime? He passed out a leaflet opposing America’s military draft during World War One. These outrages against free speech paved the way for the even more draconian anti-speech amendment, the Sedition Act (which, thankfully, Congress repealed). Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., writing for the majority, found an exception to the First Amendment. Speech that “creates a clear and present danger” may be prohibited and speakers prosecuted. Fortunately, Congress and prosecutorial practice have pulled back on those measures. But the blacking out of a wide swath of government activities from public view, and criminalizing discussion about those activities, remains a disturbing exception to the First Amendment. Whatever one’s opinions concerning the current and former presidents, the breadth of this law in enforcing an over-classification system run amuck is a sure sign that reform is needed. Perhaps it will take two presidents of both parties getting snared in the Espionage Act’s net to spur Congress to pass limits on the classification system and the secret state. In response to a Freedom of Information Act request filed by PPSA, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) responded with a batch of documents, including internal training material. In those documents, the ATF confirmed that it uses cell site simulators, commonly known as “stingrays,” to track Americans.

Stingrays impersonate cell towers to track mobile device users. These devices give the government the ability to conduct sweeping dragnets of the metadata, location, text messages, and other data stored by the cell phones of people within a geofenced area. Through stingrays, the government can obtain a disturbing amount of information. The ATF has gone to great lengths to obfuscate their usage of stingrays, despite one official document claiming stingrays are “used on almost a daily basis in the field.” The ATF stressed that stingrays are not precise location trackers like GPS, despite the plethora of information stingrays can still provide. Answers to questions from the Senate Appropriations Committee about the ATF’s usage of stingrays and license plate reader technology are entirely blacked out in the ATF documents we received. An ATF policy conceals the use of these devices from their targets, even when relevant to their legal defense. Example: When an ATF agent interviewed by a defense attorney revealed the use of the equipment, a large group email was sent out saying: "This was obviously a mistake and is being handled." The information released by the ATF confirms the agency is indeed utilizing stingray technology. Although the agency attempted to minimize usage the usage of stingrays, it is clear they are being widely used against Americans. PPSA will continue to track stingray usage and report forthcoming responses to pending Freedom of Information Act requests with federal agencies. Secrecy makes us naturally distrustful of other people. When we sense that someone else is withholding information, we can’t help but feel suspicious of their motives. This may be why the State Department’s continued efforts to hide information from the American public, routinely through overclassification, leaves a sour taste in the mouth.

The State Department is no stranger to the misuse of classification procedures: in May, PPSA reported on the Department’s Self-Inspection Report, which we obtained through a Freedom of Information Act Request. The report detailed minimal instances where information was in some way misclassified. At the time, PPSA called the report into question, as it seemed statistically impossible that only a few dozen articles were misclassified out of over 70 million classifications. Furthermore, the State Department only polled a sample of their classifications, meaning there are undoubtedly more misclassifications than reported. PPSA recently received an additional batch of documents from the State Department which only further cement our prior concern. According to internal documents spanning several years, the Department has failed to correct a “significant lack of portion marking,” when conducting classification. Portion marking refers to the process of marking specific portions of a record as classified, as opposed to the entire record. This means that entire documents have been classified where only smaller portions should have been. PPSA will continue to report on overclassification in the State Department as more information becomes available. The Project for Privacy and Surveillance Accountability today released training documents for U.S. Attorneys obtained from a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to the Department of Justice. The results show that U.S. Attorneys are encouraged to “always” seek non-disclosure orders when surveilling Americans – and to “ask for it all!”

Armed with such non-disclosure orders (NDOs), prosecutors block service providers from informing Americans that their personal information, often in the cloud, has been searched by the government. It was already known that this was a common practice, but the documents from the U.S. Executive Office for United States Attorneys show that it is virtually required.

With no legal guardrails and in the face of departmental encouragement, why not, indeed? The NDO Fairness Act, sponsored by Judiciary Chairman Jerry Nadler (D-NY) and Rep. Scott Fitzgerald (R-WI) passed the House of Representatives in June in a bipartisan voice vote. This law would restrain the use of NDOs, allowing Americans to be informed by service providers that they’ve been surveilled, with reasonable exceptions. “In the 21st century federal prosecutors no longer need to show up to your office,” Chairman Nadler told his colleagues on the House Judiciary Committee in discussing the NDO Fairness Act. “They just need to raid your virtual office. They do not have to subpoena journalists directly. They just need to go to the cloud. And rather than providing Americans with meaningful notice that their electronic records are being accessed in a criminal investigation, the Department hides behind its ability to ask third-party providers directly. They deny American citizens, companies, and institutions their basic day in court and, instead, they gather their evidence entirely in secret.” Nadler also noted that the executive branch had targeted journalists and their sources, as well as Members of Congress, their staffs, and their families. Jim Jordan, the Ranking Member of the House Judiciary Committee, said “the laws and guidelines governing surveillance are opaque, antiquated, and easily skirted. Our system of warrants, subpoenas, national security letters, secret courts, and other tools at the government’s disposal must be brought in line with the constitutional considerations of basic due process.” The NDO Fairness Act would insert necessary guardrails by amending 18 U.S.C. 2705 to:

“The direction to ‘always’ seek an NDO with a subpoena or warrant – and to ‘ask for it all’ – should spur the Senate to follow suit and pass the NDO Fairness Act,” said Bob Goodlatte, former Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee and PPSA Senior Policy Advisor. “This strong stand by the House now puts the spotlight on senators to pass this reasonable restraint of the government’s ability to thumb through our personal information.” FBI Decides FOIA Doesn’t Require Search for More than One Document on Secret Court Opinions12/5/2022

In a new low for the FBI’s processing of Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, the Bureau now states it believes it does not need to keep searching for records after locating a single potentially responsive record. This is contrary to both the FOIA statute and common sense. If the FBI were correct, every FOIA requester would be entitled to just a single record, and countless government activities would remain hidden from the public.

This is the latest disappointing response from the FBI. We recently reported that the FBI asserts – in response to our request for FBI records of opinions from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) and its court of review – that it cannot locate these court opinions on its revised computer system. As excuses go, this is a dog-ate-my-homework level of sophistication. Now we’re forced to appeal the FBI’s non-response response to our FOIA request for information on all the Bureau’s records on FISC opinions. The FBI’s hungry dog is still at work: they’ve responded to our request by also stating that it located a single record and then stopped searching. In the FBI’s mind, it “expeditiously” released “documents” that fulfilled PPSA’s request. But there were no “documents,” plural. The FBI produced only one document, with 40 pages of this one document redacted to the point of unintelligibility. And the FBI didn’t even try to find anything else. In our administrative appeal, PPSA told the FBI’s Director of Information Policy: “Discontinuing a search after finding a single, previously-released record is evidence of a search that was not reasonably calculated to uncover all responsive documents. This is made clear by the FBI’s statement that PPSA could also request an ‘additional search for records.’ That is not PPSA’s job; PPSA already submitted a request for all responsive records.” As for the redactions in this one document, PPSA has demanded that the FBI provide it additional information to justify the redactions. When an agency redacts an entire document, requesters like PPSA are at an obvious disadvantage in trying to challenge those withholdings. To recycle a famous legal quote, the government is “holding a grab bag and saying, ‘I’ll give you this if you can tell me what’s in it.’” We fully expect the FBI to be disingenuous. But we are hopeful that the FBI’s Director of Information Policy will at least be embarrassed by the thinness of the FBI’s recent excuses. Last week PPSA appealed a federal district court decision denying our motion under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) to force the FBI to produce records concerning the agency’s “unmasking” of various Members of Congress. Although the legal issue in this case may seem technical and abstruse, the legal question PPSA presents is important to Americans’ ability to hold our government accountable for surveillance directed at all of us.

These are the kinds of overarching, important concerns behind our FOIA requests. But such larger issues are often subsumed along the way in legal wrangling. These cases often center around the government’s efforts to avoid responding to a FOIA at all. At first blush, the FOIA process seems straightforward. You might imagine that: PPSA files a FOIA request seeking records concerning surveillance practices, training, or procedures to a given government agency; the request is transmitted to the relevant agency component; and then the agency produces responsive records a few weeks later and we publicize them. After all, that is what FOIA requires. But things are never so easy with FOIA. Government agencies routinely employ delaying tactics and denials to frustrate and exhaust even the most persistent requesters. In addition to simply ignoring requests, FBI and other agencies rely on a judicially invented doctrine called the Glomar response to claim that they are not even required to confirm or deny the existence of records about a given subject. Elsewhere, agencies claim that they don’t need to comply with FOIA because it would be too burdensome, as if digital search engines had yet to reach government record-keeping. Such responses were meant by Congress to be rare exceptions to the rule. In practice, they’ve become the rule. In the face of such obstructionism from officialdom, PPSA always takes the long view. A FOIA request is just the opening play in a long set. A denial, often on Glomar grounds, is the customary result. Once we receive an official denial to our request (usually long past the statutory deadline), PPSA then files an administrative appeal. Barring a satisfactory result (which is rare), we take the agency to court. So we were not surprised when a judge on the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia upheld the government’s argument that it cannot respond to a FOIA request we filed in 2020. PPSA had asked for documents concerning government identification, or “unmasking,” of 48 sitting and former members of congressional intelligence committees in their communications from 2008 to 2020. Predictably, the government pled “Glomar,” and the judge agreed. So we are appealing. In another case, PPSA was surprised when a request for FBI records of opinions from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) was denied because – the FBI asserted – it cannot locate these court opinions on its revised computer system. As excuses go, this is a dog-ate-my-homework level of sophistication. This is where flabber goes to meet with gasted. If the FBI truly cannot locate FISC opinions directed at the Bureau, we are truly in trouble. In this instance, PPSA is pursuing an administrative appeal to DOJ’s Office of Information Policy. The appeal is couched in the customary legalese, but the gist of it is: “C’mon guys, this last one doesn’t pass the laugh test.” Following FOIA requests on their long journeys is a tough, gritty business. But, as they say, it may be a dirty job, but someone has to do it. |

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed