|

Why did the “unmasking” of Americans’ identities in the global data trawl of U.S. intelligence agencies increase by 172 percent, from 11,511 times in 2022 to 31,330 times in 2023?

Government officials briefing the media say that most of this increase was a defensive response to a hostile intelligence agency launching a massive cyberattack on U.S. infrastructure, possibly infiltrating the digital systems of dams, power plants, or the like. What we do know for sure is that this authority has been abused before. Unmasking occurs when American citizens or “U.S. persons” are caught up, incidentally, in warrantless foreign surveillance. When this happens, the identities of these Americans are routinely hidden from government agents, or “masked.” But senior officials can request that the NSA “unmask” those individuals. This should be a relatively rare occurrence. Yet for some reason, over a 12-month period between 2015 and 2016, the Obama Administration unmasked 9,217 persons. Former UN Ambassador Samantha Power, or someone acting in her name, was a prolific unmasker. Power’s name was used to request unmasking of Americans more than 260 times. Large-scale unmasking continued under the Trump administration, with 2018 seeing 16,721 unmaskings, an increase of 7,000 from the year before. In recent years, the number hovered around 10,000. Now it is three times that many. This is a concern if some subset of these unmaskings (which mostly involve an email account or IP address, not a name) were for named individuals for political purposes. Consider that in 2016, at least 16 Obama administration officials, including then-Vice President Joe Biden, requested unmaskings of Donald Trump’s advisors. Outgoing National Security Advisor Susan Rice took a particular interest in unmasking members of President-elect Trump’s transition team. We are left to wonder if all of this rise in unmasking numbers can be explained away by Chinese or Russian hackers, or if some portion of them reflect the use of this authority for political purposes. Were prominent politicians, officeholders, or candidates unmasked? These raw numbers come from the government’s Annual Statistical Transparency report. This report on intelligence community activities from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence offers revealing numbers, but often without detail or explanation that would explain such jumps. All we have to rely on are media briefs that at times seem more forthcoming than the briefings available to Members of Congress, even those tasked with oversight of intelligence agencies in the House and Senate Judiciary Committees. As these numbers rise, the American people deserve more information and a solid assurance that these authorities will never again be used for political purposes by either party. The Drug Enforcement Administration’s response to three PPSA Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests shows just how far government respect for that law has fallen. As we’ve seen recently with other government agencies, DEA didn’t even try to pretend it was following that law.

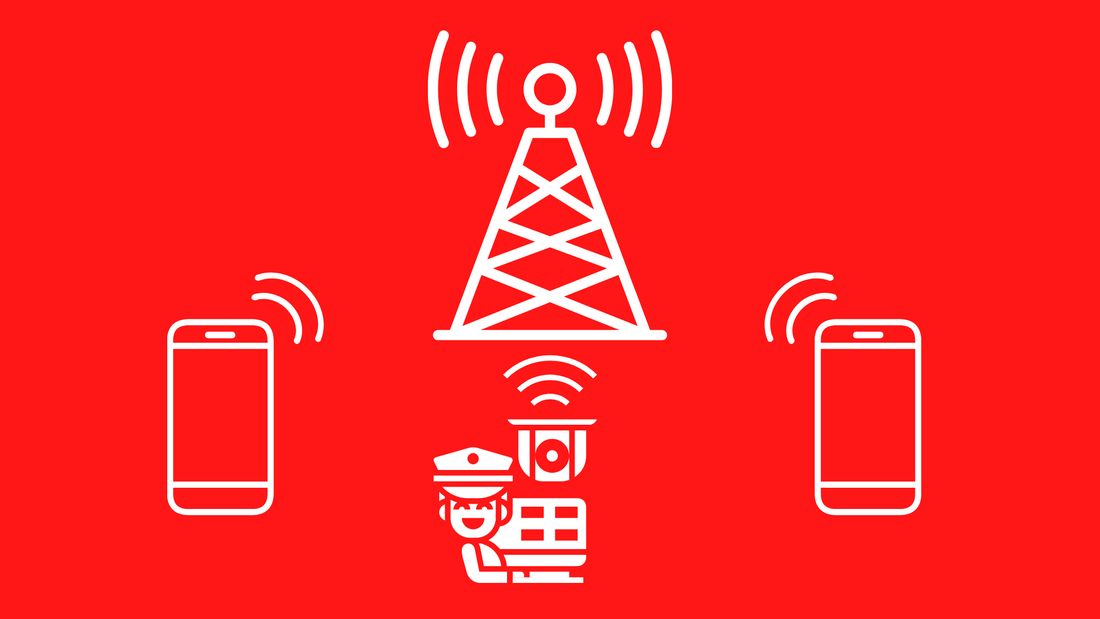

Over the course of a year, PPSA filed three FOIA requests with the DEA seeking documents relating to the use of cell-site simulators, commonly known by the trade name Stingray. Government agencies use these devices to mimic cell towers, pinging consumers’ cellphones in a given geographic area to prompt them to give up private location data, and sometimes the content of communications. PPSA sought records since 2015 that reflect each use of a cell-site simulator by DEA that was conducted without a warrant based on emergency, exceptional, or “exigent” circumstances. We thought it would be a useful guide for public policy to know how often the agency defined something as an emergency, side-stepping the need to obtain a probable cause warrant. On Monday, DEA came back with one combined response to all three FOIAs we had issued over the course of many months. If DEA had followed the law, it would have conformed to a federal precedent, Truitt v. Department of State (1990), which held that it “is elementary that an agency responding to a FOIA request must conduct a search reasonably calculated to uncover all relevant documents, and if challenged, must demonstrate beyond material doubt that the search was reasonable.” Instead, DEA did not even try to pass the laugh test. It waved away all three FOIA requests citing an exemption that covers personnel documents and other Human Relations files. How could PPSA’s request for the use of cell-site simulators for emergency circumstances, in the words of the law, fall under an exemption for subjects that relates “solely to the internal personnel rules and practices of an agency”? In a letter to the Director of Information Policy of the Department of Justice, PPSA general counsel Gene Schaerr responded: “It is almost certain that at least some documents concerning broader surveillance policy or related record-keeping would be responsive. Of course, DEA does not know one way or the other whether this is accurate because it refused to look for responsive records.” How would DEA know that this request only involved personnel records without a responsive search? It is clear that DEA simply wanted to clear this one FOIA request off its desk. We wish this case was an exception. Federal FOIA responses are becoming increasingly farcical. A FOIA response from the Department of Justice included 40 redacted pages with an insulting valediction – “hope that’s helpful.” Expect this lawless attitude toward the Freedom of Information Act to continue until courts step in and start leveling sanctions against those who treat the law as an ignorable suggestion. Will Dream Security Tech Be Marketed More Ethically than Pegasus?According to the Wall Street Journal, Shalev Hulio, former chief executive of NSO Group, the company behind the controversial Pegasus spyware, has launched a new cybersecurity firm in the wake of the Israel-Hamas war. The company, Dream Security, uses artificial intelligence to identify and analyze cyber threats.

So far, the company is already valued at more than $200 million, with customers in Israel and Europe. The need is obvious: European governments and other critical infrastructure have seen increased cyber risks since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. After the recent Hamas raid and atrocities, Israel itself has become a red-hot target. Israel needs and deserves every advantage it can muster in protecting itself. But given the history of NSO and Pegasus, we must raise concern about the risks if Dream Security products were to be sold – as Pegasus was – to irresponsible and dangerous foreign governments and hostile actors. Pegasus has already been implicated in facilitating the murder of journalists and at least one dissident, spying on State Department discussions about an abducted American, and used by politicians in Spain and India against journalists and rivals. Artificial intelligence is a nascent technology. There is no telling how it may yet impact the evolving nature of modern warfare, even if developed for defensive purposes. We support any technology that enhances the security of the Israeli people. But it is in everybody’s best interests that Dream Security commits to only doing business with responsible state and corporate actors. PPSA will be monitoring this story as it develops. Apple Sends Notice of Hack Pegasus – the Israeli-made spyware – continues to proliferate and enable bad actors to persecute journalists, dissidents, opposition politicians, and crime victims around the world.

This spyware transforms a smartphone into the surveillance equivalent of a Swiss Army knife. Pegasus has a “zero-day” capability, able to infiltrate any Apple or Android phone remotely, without requiring the users to fall for a phishing scam or click on some other trick. Once uploaded, Pegasus turns the victim’s camera and microphone into a 24/7 surveillance device, while also hoovering up every bit of data that passes through the device – from location histories to text, email, and phone messages. We’ve written about how Mexican cartels have used Pegasus to track down and murder journalists. We’ve covered the role of Pegasus in the murder of Saudi dissident Adnan Khashoggi, and how an African government used it to spy on an American woman while she was receiving a briefing inside a State Department facility on her father’s abduction. Now fresh evidence from Apple alerts shows how Pegasus continues to be used by governments to spy on political opponents. Journalists have learned that the Israeli-based NSO Group has sold its spyware to at least 10 governments. Two years ago, it was revealed that a government had used Pegasus to surveil Spanish politicians, including the prime minister, as well as regional politicians. Now it is happening in India. On Oct. 31, just in time for Halloween, Apple sent notices to more than 20 prominent journalists, think tank officials, and politicians in opposition to Prime Minster Narenda Modi that hacking attempts had been made on their smartphones. In 2021, The Washington Post and other media organizations investigated a list obtained by Forbidden Stories, a Paris-based non-profit media outlet, tracking down more than 1,000 phone numbers of hundreds of prominent Indians who were set to be surveilled by Pegasus. This plan now seems to have been executed, at least in part. “Spyware technology has been used to clamp down on human rights and stifle freedom of assembly and expression,” said Likhita Banerj of Amnesty International. “In this atmosphere, the reports of prominent journalists and opposition leaders receiving the Apple notifications are particularly concerning in the months leading up to state and national elections.” Yesterday Spain, today India, tomorrow the United States? It is public knowledge that the FBI owns a copy of Pegasus and that a recent high-level government attorney from the intelligence community has signed on to represent the NSO Group. This is all the more reason for Congress to pass serious reforms to Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, to curtail all forms of illicit government surveillance of Americans. PPSA will continue to monitor this story. “Fruit of a Poisonous Tree”FBI documents acquired through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests by PPSA and the American Civil Liberties Union show how authorities continue to conceal information about how stingray technology is really being used. The downstream effect of this deception likely results in defendants being denied the ability to know how a case was constructed against them, degrading their right to a fair trial.

Dozens of federal and state agencies have benefitted from the generosity of the Department of Justice in sharing with state and local police cell-site simulators, popularly known by the brand name “Stingrays.” These devices trick cellphones into revealing their owners’ locations and other sensitive, personal information. An email from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), released today by PPSA, one ATF official writes to another: “To remain consistent with our DOJ Partner, in this case, the USMS (U.S. Marshall Service) since they are the largest user of this technology, we respectfully request that this technique not be disclosed in an affidavit.” ACLU’s FOIA shows the same instructions from the federal government imposed in nondisclosure agreements on police departments when they ask for this technology to track suspects. These contracts don’t beat around the bush. They explicitly require police departments to withhold information about stingrays and their usage from defendants and lawyers. The FBI argues that such secrecy is required to prevent revealing information that would enable criminals to “thwart law enforcement efforts.” But what’s the big secret? Despite the clandestine nature of this federal/local partnership program, stingray technology and its capabilities have been an open secret for years now. This technology was depicted under another brand name – “triggerfish” –on season three of HBO’s The Wire. That was in 2004. Could the real secret be that police departments are conspiring with the FBI to conceal the use of privacy-invading technology to give prosecutors an unfair, “backdoor” advantage in their cases? PPSA has often reported the ways in which federal or state agencies routinely circumvent constitutional privacy protections. One well-known method is the parallel construction of evidence, in which prosecutors leverage illicitly gained knowledge to turn up evidence from a source acceptable in court. It is well established legal doctrine that illicit evidence, the “fruit of the poisonous tree,” should not be admissible. But who knows what is poisonous if the tree is hidden? The acquired federal documents actually spell out how parallel construction should work – advising the police to pursue “additional and independent investigative means and methods” to obtain evidence collected through use of a cell-site simulator. The suggestions on how to accomplish such secrecy were redacted by the FBI. The Bureau argues that revealing information about stingrays would have a “significant detrimental impact on the national security of the United States.” The revelation of even minor details is so heavily restricted that police have dropped charges against a suspect rather than unveil information in open court. “The important question posed by privacy advocates is why are police departments and the FBI going to such lengths to conceal information about a technology that is public knowledge?” asked Bob Goodlatte, former chairman of the House Judiciary Committee and PPSA Senior Policy Advisor. “The capabilities of stingrays are well-known, with knowledge of their deployment on popular television almost twenty years ago. “Yet the government still insists that the basics of stingray use is a precious national secret,” Goodlatte said. “Congress should demand to know if there is any basis at all for these non-disclosure agreements – and how common parallel construction really is in practice.” Credit to the Department of Justice for a voluminous response to our Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. Our request concerned the use of stingrays, or cell-site simulators, by that department and its agencies. Out of more than 1,000 pages in DOJ’s response, we’ve found a few gems. Perhaps you can find your own.

Review our digest of this document here, and the source document here. The original FOIA request concerned DOJ policies on cell-site simulators, commonly known by the commercial brand name “stingrays.” These devices mimic cell towers to extract location and other highly personal information from your smartphone. The DOJ FOIA response shows that the FBI in 2021 invested $16.1 million in these cell-site simulators (p. 209) in part to ensure they “are capable of operating against evolving wireless communications.” The bureau also asked for $13 million for “communications intercept resources.” This includes support for the Sensitive Investigations Unit’s work in El Salvador (p. 111). On the policy side, we’ve reported that some federal agencies, such as the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, maintain that stingrays are not GPS location identifiers for people with cellphones. This is technically true. Stingrays do not download location data or function as GPS locators. But this is too clever by half. Included in this release is an Obama-era statement by former Department of Justice official Sally Yates that undermines this federal claim by stating: “Law enforcement agents can use cell-site simulators to help locate cellular devices whose unique identifiers are known …” (p. 17) This release gives an idea of how versatile stingrays have become. The U.S. Marshals Service (p. 977) reveals that it operates cell-site simulators and passive wireless collection sensors to specifically locate devices inside multi-dwelling buildings. Other details sprinkled throughout this release concern other, more exotic forms of domestic surveillance. For example, the U.S. Marshals Service Service has access to seven aircraft located around the country armed with “a unique combination of USMS ELSUR suite, high resolution video surveillance capability … proven to be the most successful law enforcement package” (p.881-883). A surveillance software, “Dark HunTor,” exposes user data from Tor, the browser meant to make searches anonymous, as well as from dark web searches for information. (p. 105) In addition, the U.S. Marshals Service Service “has created the Open-Source Intelligence Unit (OSINT) to proactively review and research social media content. OSINT identifies threats and situations of concern that may be currently undetected through traditional investigative methods. Analyzing public discourse on social media, its spread (‘likes,’ comments, and shares), and the target audience, the USMS can effectively manage its resources appropriate to the identified threats.” (p. 931) The DOJ release also includes details on biometric devices, from facial recognition software to other biometric identifiers, (p.353), as well as more than $10 million for “DNA Capability Expansion” (p.365). Is that all? Feel free to look for yourself. Our government can operate in grey areas of the law because agencies have become adept at exploiting every loophole, exception, or tiny bit of leeway in a statute. PPSA announces today the submission of two Freedom of Information Act requests to the Department of Justice to shed light on practices in two such areas of concern – surveillance of cellphone data by devices that imitate cell towers, and the role of privacy experts in a secret court.

The first FOIA request concerns cell-site simulators that law enforcement agencies use to mimic cell towers, allowing them to snatch location data and other information from the cellphones of people at a given location. These devices, commonly known as “stingrays,” are used to track people by pinging their phones. This digital intrusion is at odds with the spirit of the Supreme Court opinion in Carpenter v. United States, where the Court in 2018 rejected unlimited government access to cellphone location data. But the high Court did not specifically ban cell-site simulators. So, with this tiny distinction, stingrays are still commonly used by 14 federal agencies and police in cities around the country. In 2015, the Department of Justice did produce a memo requiring a warrant for some uses of this technology. That memo, however, allows federal agencies free use of this technology in “exigent” circumstances. How dire does a circumstance have to be to be “exigent”? Virtually everyone agrees that if a child is thrown into a stranger’s car, or a terrorist is known to be planting a bomb, law enforcement should be able to get their hands on stingray data in an instant. But given the slipperiness with which the government defines legal terms, what are the actual circumstances in which stingrays have been used?

In this way, PPSA is seeking to discover if federal agencies are playing fair with the “exigent” exception. PPSA’s second FOIA request concerns the use – or rather, the non-use – of amicus advisors by the FISC. A little history is in order. When Judge James E. Boasberg of the secret court heard requests from the FBI for permission to surveil presidential campaign aide Carter Page, the judge could have sought advice from a privacy lawyer with high-security clearance. Such an amicus could have helped guide the judge through the competing issues in a case fraught with civil liberty concerns, not the least of which were the First Amendment rights of 137.5 million voters. Judge Boasberg demurred. It appears he did not seek an amicus and missed spotting a circus of misdirection and shocking omissions in the FBI’s requests, including submission by an FBI lawyer of a forged document. It is with this in mind that we supported the Leahy-Lee measure in the previous Congress that would bring checks and balances into FISC proceedings. This legislation would bring to the one-sided nature of FISC hearings a privacy-oriented advocate to independently verify the FISA application’s material assertions whenever a case touches on the civil rights of sensitive cases involving political campaigns, federal officials, the practice of journalism, religious minorities, or other sensitive areas. Since this is not the law, PPSA filed this FOIA request.

We would prefer not to have to pull out a legal microscope. But given the disingenuous way our government finds exceptions for lawless acts, we feel they have given us no choice. PPSA will report on any responses. PPSA recently reported that the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), in a response to our Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, downplayed its use of stingrays, as cell-site simulators are commonly called. Yet one agency document revealed that stingrays are “used on almost a daily basis in the field.” This was a critical insight into real-world practice. These cell-site simulators impersonate cell towers to track mobile device users. Stingray technology allows government agencies to collect huge volumes of personal information from many cellphones within a geofenced area. We now have more to report with newly-released documents that, as before, include material for internal training of ATF agents. One of the most interesting findings is not what we can see, but what we can’t see – the parts of documents ATF takes pains to hide. The black ink covers a slide about the parts of the U.S. radio spectrum. Since this is a response to a FOIA request about stingrays, it is likely that the spectrum discussed concerns the frequencies telecom providers use for their cell towers. What appears to be a quotidian training course for agents on electronic communications has the title of the course redacted. If that is so, was there something revealing about the course title that we are not allowed to see? Could it be “Stingrays for Dummies?” The redactions also completely cover eleven pages about pre-mission planning. Do these pages reveal how ATF manages its legal obligations before using stingrays? This course presentation ends somewhat tastelessly, a slide with a picture of a compromised cell-tower disguised as a palm tree. In the release of another tranche of ATF documents, forty-five pages are blacked out. It appears from the preceding email chain that these pages included subpoenas for a warrant executed with the New York Police Department. The document assigns any one of a pool of agents to “swear out” a premade affidavit to support the subpoena. The ATF reveals it uses stingrays on aircraft, which requires a high level of administrative approval. It seems, however, from an ATF PowerPoint presentation that this is a policy change, which suggests that prior approvals were lax. Was this a reaction to the 2015 Department of Justice’s policy on cell-site simulators? If aerial surveillance now requires a search warrant, what was previously required – and how was such surveillance used? Was it used against whole groups of protestors? Finally, the documents reveal that the ATF has had cell-site simulators in use in field divisions in major cities, including Chicago, Denver, Detroit, Houston, Kansas City, Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Tampa, as well as other cities. PPSA will report more on ATF’s ongoing document dumps as they come in. By The Way... Here's How ATF Glosses Over Its Location TrackingThe training manual of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives states that cell-site simulators “do not function as a GPS locator, as they do not obtain or download any location information from the device or its applications.” This claim is disingenuous. It is true that exact latitude and longitude data are not taken. But by tricking a target’s phone into connecting and sending strength of signal data to a cell tower, the cell-site simulator allows the ATF to locate the cellphone user to within a very small area. If a target uses multiple cell-site simulators, agents can deduce his or her movements throughout the day.

Below is an example from a Drug Enforcement Agency document that shows how this technology can be used to locate a target (seen within the black cone) in a small area. The Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board (PCLOB) has posted a rich discussion among its board members, civil libertarians, and representatives of the intelligence community.

General Paul Nakasone, who heads the U.S. Cyber Command, gave the group a keynote address that is a likely harbinger of how the intelligence community will approach Congress when it seeks reauthorization of Section 702, an amendment to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act that authorizes the government to surveil foreigners, with a specific prohibition against the targeting of Americans, but also allows “incidental” surveillance of Americans. Gen. Nakasone detailed cases in which would-be subway bombers and ISIS planners were disrupted because of skillful use of 702 surveillance. Mike Harrington of the FBI doubled down with a description of thwarted attacks and looming threats. April Doss, general counsel of the National Security Agency, emphasized how each request from an analyst for surveillance must be reviewed by two supervisors. Civil liberties scholar Julian Sanchez reached back to the formation of the U.S. Constitution to compare today’s use of Section 702 authority to the thinking behind the Fourth Amendment. He asked if a program that mixes the private data of Americans with surveilled foreigners could possibly clear the Founders’ objection to general warrants. (31:50) Jeramie Scott (40:25) of the Electronic Privacy Information Center, who argued for greater transparency in 702 collection, questioned whether “about” collection truly ended with downstream collection (i.e., information taken directly from Google, Facebook, and other social media companies). The NSA declared in 2017 it had ended the practice of such “about” collection, which moves beyond an intelligence target to email chains and people mentioned in a thread. Could such collection still be occurring in downstream surveillance? Travis LeBlanc, a board member who had previously criticized a milquetoast report from PCLOB for a lack of analysis of key programs, seemed liberated by the board’s new chair, Sharon Bradford Franklin. (Chair Franklin also brings a critical eye of surveillance programs, reflecting her views at the Center for Democracy and Technology.) LeBlanc asked Julian Sanchez if the Constitution requires warrants when an individual’s data is searched under Section 702. Sanchez said that delegating such an authority under the honor system has led to FBI’s behaving as if compliance were a game of “whack-a-mole.” (57:15) Cindy Cohn of the Electronic Frontier Foundation suggested PCLOB examine Section 702’s tendency to be subject to “mission creep,” such as the recent practice of using Section 702 to justify surveillance for “strategic competition” as well as the statutory purpose of anti-terrorism. Cohn said she was not aware of any defendant in a criminal trial ever getting access to Section 702 evidence. (128:45) Cohn concluded: “I think we have to be honest at this point that the U.S. has de facto created a national security exception to the U.S. Constitution.” A revealing insight came from Jeff Kosseth, cybersecurity professor at the U.S. Naval Academy. He pointed to a paper he wrote with colleague Chris Inglis that concluded that Section 702 is “constitutional” and “absolutely essential for national security.” (See 143:40) That opinion, Kosseth added, is something he has “reconsidered” over “deep concern about the FBI’s access” to 702 data, especially concerning U.S. persons. Kosseth said: “At a certain point, we must stop giving the nation’s largest law enforcement agency every benefit of the doubt. The FBI cannot play fast and loose with Americans’ most private information. This has to stop now. And if the FBI cannot stop itself, the Congress has to step in.” Congress needs to “step in” regardless: surveillance of Americans should never occur without express authority in a statute passed by the people’s representatives. In response to a Freedom of Information Act request filed by PPSA, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) responded with a batch of documents, including internal training material. In those documents, the ATF confirmed that it uses cell site simulators, commonly known as “stingrays,” to track Americans.

Stingrays impersonate cell towers to track mobile device users. These devices give the government the ability to conduct sweeping dragnets of the metadata, location, text messages, and other data stored by the cell phones of people within a geofenced area. Through stingrays, the government can obtain a disturbing amount of information. The ATF has gone to great lengths to obfuscate their usage of stingrays, despite one official document claiming stingrays are “used on almost a daily basis in the field.” The ATF stressed that stingrays are not precise location trackers like GPS, despite the plethora of information stingrays can still provide. Answers to questions from the Senate Appropriations Committee about the ATF’s usage of stingrays and license plate reader technology are entirely blacked out in the ATF documents we received. An ATF policy conceals the use of these devices from their targets, even when relevant to their legal defense. Example: When an ATF agent interviewed by a defense attorney revealed the use of the equipment, a large group email was sent out saying: "This was obviously a mistake and is being handled." The information released by the ATF confirms the agency is indeed utilizing stingray technology. Although the agency attempted to minimize usage the usage of stingrays, it is clear they are being widely used against Americans. PPSA will continue to track stingray usage and report forthcoming responses to pending Freedom of Information Act requests with federal agencies. An elegant essay by Adrian Wooldridge in Bloomberg makes a connection between the Chinese surveillance state – “using the awesome power of data harvesting and artificial intelligence to compile more information on its citizens than any society has ever managed before” – and Western “surveillance capitalists” who are making our country a little more like China day by day.

PPSA has long warned that all the elements are falling into place to create an American surveillance state. Here are just a few of the ways in which this is happening: The federal government and local police departments use “stingray” technology to trick Americans’ phones to betray your location and other personal information. Authorities can purchase your location history with Fog Reveal technology and capture all your comings and goings. Or they can just buy your personal information from a private data broker, as many federal agencies do. The growing web of the “internet of things” will only produce more reportable data about you, from the cars we drive, to our refrigerators and other appliances in our home. A surveillance loophole was even recently found in a Chinese-made coffee maker. Wooldridge reports that the Chinese Communist Party is at the cutting edge, “developing a new sort of ‘digital phrenology’ by monitoring people’s facial expression for signs of anger and new forms of racial profiling by creating a world-leading DNA database.” Governments, including our own, exert “relentless pressure for the misuse of information even as the quality and quantity of available information grows exponentially.” The techno-optimists of the 1990s waxed rhapsodic about how the internet was going to liberate the human mind. Wooldridge comes to an opposite conclusion with these chilling words: “The arc of the digital revolution bends toward tyranny.” Agencies Avoid Answering Questions About the Purchase of Private Information of Members of CongressSince the mid-1960s, the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) has allowed American citizens and civil liberties organizations to obtain unclassified documents from federal agencies, shedding light on official actions and policies. In recent years, however, the government has devised many creative ways to stall, obfuscate, and outright withhold answers to FOIA requests, while seeming to be as responsive as possible. Cato Institute scholar Patrick Eddington calls these tactics “constructive denial.”

For over two years, Cato filed FOIA requests to obtain FBI records on militia groups of the left and the right, including the white supremacist Patriot Front. “Groups like the Patriot Front,” Eddington writes in The Hill, “are, in the view of most Americans, a moral and political blight that the country would be far better off without. At the same time, the protection of offensive ideas and speech are at the heart of the purpose of the First Amendment.” Thus, Cato sought records to better understand the threat posed by these groups and the nature of the government’s response. In defiance of FOIA’s requirement that the FBI send the requested documents to the requester himself, the FBI replied to Cato that it would eventually file the documents on an FBI website. “You will be notified when releases are available.” In other words, buzz off. Constructive denial can be seen in another form after PPSA filed suit against the National Security Agency, the CIA, the Department of Justice and FBI, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence in June to compel the release of records pertaining to the possible purchase of the personal information of more than 100 current and former Members of the House and Senate Judiciary Committees from private data brokers. This is understandably a sensitive question, given that current and former judiciary committee lawmakers include Chairman Jerrold Nadler, Ranking Member Jim Jordan, Chairman Dick Durbin, Ranking Member Chuck Grassley, as well as Vice President Kamala Harris and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis. Still, it would be a matter of public interest – not to mention to these legislators themselves – if the government were buying up their personal information. Such an act could yield leverage for executive branch agencies to bully leading Members of Congress, subtly undermining democracy. The agencies’ response to PPSA’s FOIA request over summer 2021 was to issue Glomar responses, a judicially invented doctrine that neither confirms nor denies that such records exist. Now that PPSA has sued to enforce its request, these agencies have come back with an answer that doubles down on a government theory that it would be too dangerous to national security for these agencies to even search for such documents. At the same time, government responses strike a tone of wanting to be as cooperative as possible. One choice example: PPSA asserted a “right of prompt access to requested records under the law.” The National Security Agency responded: “To the extent that a response is required, Defendant NSA denies the allegation, including the fact that NSA has wrongfully withheld records.” This is a construction worthy of Joseph Heller’s Catch-22. Gene Schaerr, PPSA general counsel, responds: “The government’s answers disingenuously conflate an internal search for documents with an external response to a question. The government feels free to treat FOIA as polite supplication instead of a law that must be obeyed. PPSA will continue to press on for a serious answer in federal court.” In the meantime, expect the government to come up with many new forms of constructive denial. Courts throw out cases in which the government violated the Fourth Amendment to gain evidence obtained illegally. Prosecutors, dreading such a rebuke, have sometimes resorted to “parallel construction” – using illicitly gained knowledge to turn up evidence from a source acceptable in court.

Suppose, for example, that an illegal wiretap by federal investigators reveals that a target will deliver drugs to a certain street corner. They could then alert local police to decide that specific corner is a good place for a spot-check with drug-sniffing dogs. In this way, evidence obtained by illicit surveillance can be laundered. This seems to be especially prone to happen when law enforcement relies on “stingrays” – the common name for cell-site simulators, equipment that mimics a cellphone tower to ping the location of a cellphone. The FBI, in 2014, after providing the Oklahoma City police with stingray technology, sent that department a memo telling the police that the stingray is for “lead purposes” only and “may not be used as primary evidence in any affidavits, hearings or trials.” Instead, the FBI required the police to use “additional and independent investigative means and methods, such as historical cellular analysis, that would be admissible at trial” to corroborate information obtained using the stingray. The Cato Institute’s Adam Bates analyzed such agreements and concluded that “law enforcement uses some surreptitious and, perhaps, constitutionally dubious tactics to generate a piece of evidence. In order to obscure the source of that evidence, police will use the new information as a lead to gather information from which they construct a case that appears to have been cracked using routine police work.” Perhaps because of reporting like Cato’s analysis, formal FBI agreements to sell stingrays to local law enforcement – at least those released to the public – appear to be missing this language. But what about informal agreements? In two responses to PPSA’s Freedom of Information Act requests, the FBI has used similar language in 2015 and 2020 deals to allow police to use stingrays. To be fair, these may be one-off situations. Both cases seem to have been loaner deals, in which stingrays were deployed in “exigent” or emergency circumstances. For example, one 2015 email chain shows that an agency agreed to the FBI’s request that “it is required to use additional and independent investigative means and methods, such as [redacted] that would be admissible at trial to corroborate information concerning the location of the target obtained through the use of this equipment.” Comparing this redacted language to the unredacted provisions imposed on the Oklahoma City police, it appears that the FBI continues to push local law enforcement to hide their stingray use from the courts. On the other hand, this language is missing from other NDA forms PPSA has obtained. Has the FBI abandoned this practice? Or is it continuing “off the books” in some fashion to encourage local law enforcement to launder evidence? |

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed