|

The U.S. Supreme Court held in Riley v. California (2014) that police must obtain a warrant from a judge before inspecting the digital contents of a suspect’s cellphone. The reason, the Court memorably opined, is that a cellphone holds “the privacies of life.”

But what about a backpack? Or a purse? Or a shopping bag? Such items don’t come close to having the deep privacy implications of a cellphone, which is stuffed with location data, recent call logs, emails, and personal photos. But personal carry containers, too, can hold items reasonably considered to be private. Are police free to paw through a bag or backpack, or does the same principle from Riley also apply to them? This question is central to the case of William Bembury, who was suspected by police of selling a joint containing synthetic marijuana when he was placed under arrest in a park in Lexington, Kentucky, in 2019. While Bembury was placed in handcuffs, officers searched his backpack and found a small bag of synthetic marijuana and a few dollars. However, Bembury was not wearing the backpack when police searched it – a key fact, since police are allowed to search a person under arrest, including any containers on their person, to ensure officers’ safety. But Bembury’s backpack was sitting on a park table at the time of the arrest. And Bembury never consented to the police search of it. When Bembury appealed on Fourth Amendment grounds, he won in a state appeals court. But he lost before the Kentucky Supreme Court. Kalvis Golde of Scotusblog writes of that court’s dilemma: “Acknowledging that the U.S. Supreme Court has yet to decide whether items like backpacks or purses are categorically protected by the Fourth Amendment during arrest, the state supreme court was split on how to proceed.” In the end, a majority of Kentucky Justices held that because the backpack had been immediately in Bembury’s possession, the officers were justified in their search. Bembury is now asking the Supreme Court to grant review and bring clarity to a hodgepodge of state precedents. Bembury’s petition for review asks the Supreme Court to give state courts a principle by which to draw a line between the permissible search of a person, and nearby “purses, backpacks, suitcases, briefcases, gyms bags, computer bags, fanny packs, etc.” The appeal notes “there is little uniformity” with state courts that “have not yet parsed this issue in those exact terms.” Justices might feel that this case itself is a bit of a Pandora’s backpack. Without a clear standard, police are free to paw though any object they wish. On the other hand, a suspect carrying a backpack stuffed with contraband might simply toss it a few yards away and refuse to allow officers’ to inspect it. The Court might consider that it is odd that a clearer standard exists in the digital world with cellphones under Riley (though still sometimes honored in the breach) than with physical objects an arm’s reach away from a suspect. The high Court should consider granting a review of this case to bring clarity to how the law treats evidence in thousands of cases every year. A recent House hearing on the protection of journalistic sources veered into startling territory.

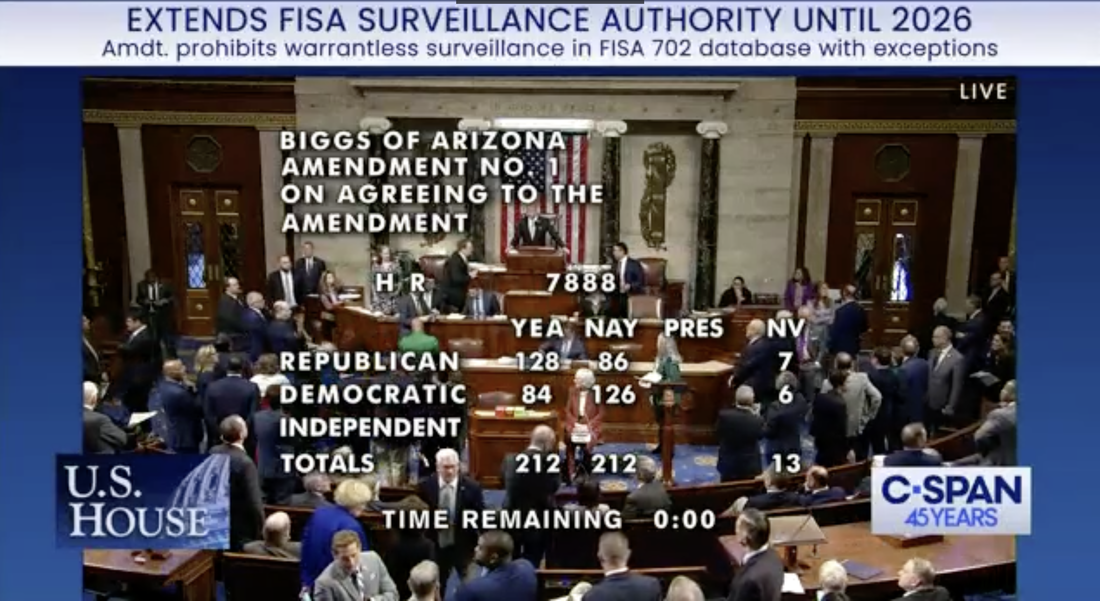

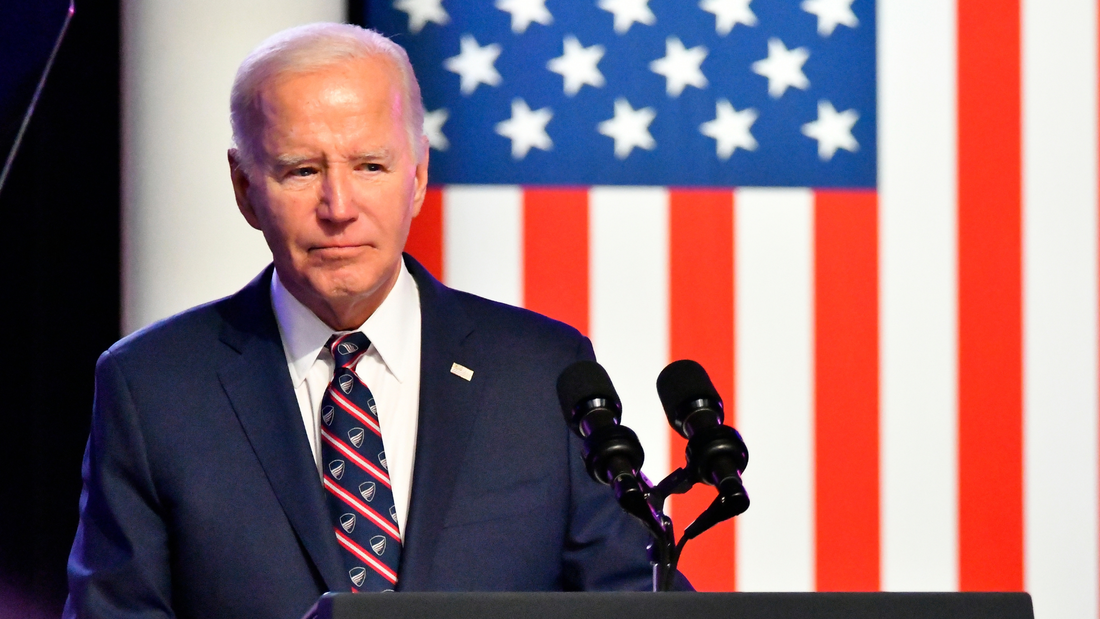

As expected, celebrated investigative journalist Catherine Herridge spoke movingly about her facing potential fines of up to $800 a day and a possible lengthy jail sentence as she faces a contempt charge for refusing to reveal a source in court. Herridge said one of her children asked, “if I would go to jail, if we would lose our house, and if we would lose our family savings to protect my reporting source.” Herridge later said that CBS News’ seizure of her journalistic notes after laying her off felt like a form of “journalistic rape.” Witnesses and most members of the House Judiciary subcommittee on the Constitution and Limited Government agreed that the Senate needs to act on the recent passage of the bipartisan Protect Reporters from Exploitative State Spying (PRESS) Act. This bill would prevent federal prosecutors from forcing journalists to burn their sources, as well to bar officials from surveilling phone and email providers to find out who is talking to journalists. Sharyl Attkisson, like Herridge a former CBS News investigative reporter, brought a dose of reality to the proceeding, noting that passing the PRESS Act is just the start of what is needed to protect a free press. “Our intelligence agencies have been working hand in hand with the telecommunications firms for decades, with billions of dollars in dark contracts and secretive arrangements,” Attkisson said. “They don’t need to ask the telecommunications firms for permission to access journalists’ records, or those of Congress or regular citizens.” Attkisson recounted that 11 years ago CBS News officially announced that Attkisson’s work computer had been targeted by an unauthorized intrusion. “Subsequent forensics unearthed government-controlled IP addresses used in the intrusions, and proved that not only did the guilty parties monitor my work in real time, they also accessed my Fast and Furious files, got into the larger CBS system, planted classified documents deep in my operating system, and were able to listen in on conversations by activating Skype audio,” Attkisson said. If true, why would the federal government plant classified documents in the operating system of a news organization unless it planned to frame journalists for a crime? Attkisson went to court, but a journalist – or any citizen – has a high hill to climb to pursue an action against the federal government. Attkisson spoke of the many challenges in pursuing a lawsuit against the Department of Justice. “I’ve learned that wrongdoers in the federal government have their own shield laws that protect them from accountability,” Attkisson said. “Government officials have broad immunity from lawsuits like mine under a law that I don’t believe was intended to protect criminal acts and wrongdoing but has been twisted into that very purpose. “The forensic proof and admission of the government’s involvement isn’t enough,” she said. “The courts require the person who was spied on to somehow produce all the evidence of who did what – prior to getting discovery. But discovery is needed to get more evidence. It’s a vicious loop that ensures many plaintiffs can’t progress their case even with solid proof of the offense.” Worse, Attkisson testified that a journalist “who was spied on has to get permission from the government agencies involved in order to question the guilty agents or those with information, or to access documents. It’s like telling an assault victim that he has to somehow get the attacker’s permission in order to obtain evidence. Obviously, the attacker simply says no. So does the government.” This hearing demonstrated how important Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable searches and seizures are to the First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of the press. If Attkisson’s claims are true, the government explicitly violated a number of laws, not the least of which is mishandling classified documents and various cybercrimes. And it relies on specious immunities and privileges to avoid any accountability for its apparent crimes. Two proposed laws are a good way to start reining in such government misconduct. The first is the PRESS Act, which would protect journalists’ sources against being pressured by prosecutors in federal court to reveal their sources. The second proposed law is the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, which passed the House last week. This bill would require the government to get a warrant before it can inspect our personal, digital information sold by data brokers. And, of course, these and other laws limiting government misconduct need genuine remedies and consequences for misconduct, not the mirage of remedies enfeebled by improper immunities. The disappointments of this evening’s votes cannot hide the momentum of a civil liberties coalition that won enhanced oversight of the FBI, and reduced the next reauthorization from five years to two. We made the forces of the status quo fight on warrant requirements, whittling them down to a tie vote, despite the vociferous opposition of the administration. The growing momentum of the surveillance reform coalition reflects the 80 percent support of the American people for warrants. We’ve got the momentum and we will be back.

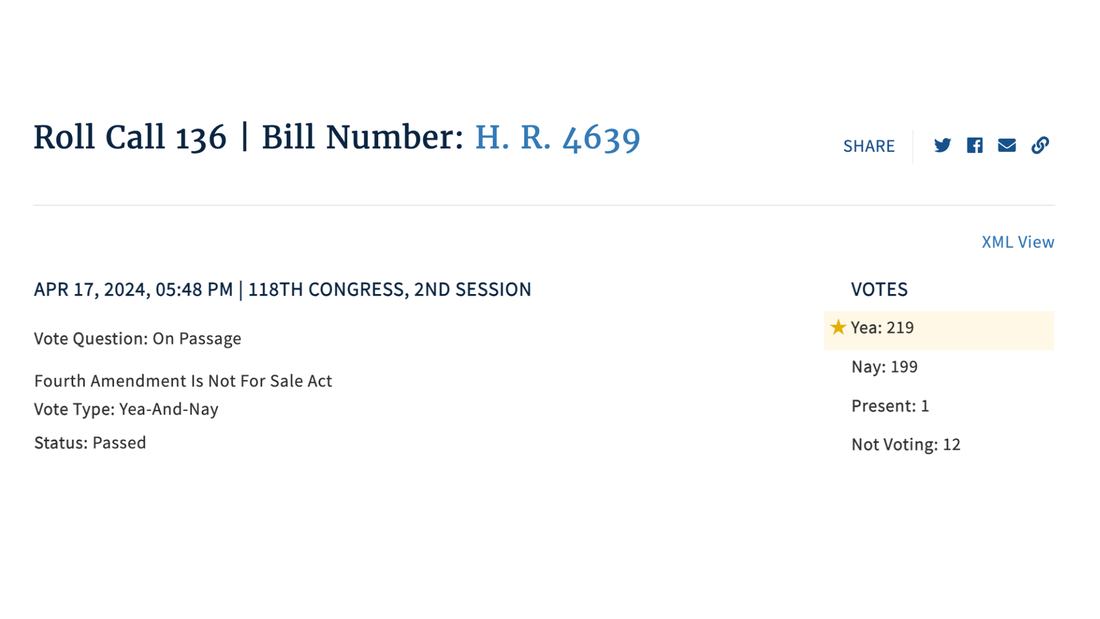

PPSA Calls on Senate to End Data Purchases The House voted 219-199 to pass the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, which requires the FBI and other federal agencies to obtain a warrant before they can purchase Americans’ personal data, including internet records and location histories.

“Every American should celebrate this strong victory in the House of Representatives today,” said Bob Goodlatte, former House Judiciary Chairman and PPSA Senior Policy Advisor. “We commend the House for stepping up to protect Americans from a government that asserts a right to purchase the details of our daily lives from shady data brokers. This vote serves notice on the government that a new day is dawning. It is time for the intelligence community to respect the will of the American people and the authority of the Fourth Amendment.” Federal agencies, from the FBI to the IRS, ATF, and the Departments of Defense and Homeland Security, for years have purchased Americans’ sensitive, personal information scraped from apps and sold by data brokers. This practice is authorized by no specific statute, nor conducted under any judicial oversight. “The Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act puts an end to the peddling of Americans’ private lives to the government,” said Gene Schaerr, general counsel of PPSA. “Eighty percent of the American people in a recent YouGov poll say they believe warrants are absolutely necessary before their digital lives can be reviewed by the government. It is now the duty of the U.S. Senate to finish the job and express the will of the people.” PPSA is grateful to Rep. Warren Davidson, House Judiciary Chairman Jim Jordan, Ranking Member Jerry Nadler, Reps. Andy Biggs, Rep. Pramila Jayapal, Rep. Zoe Lofgren, Rep. Thomas Massie, Rep. Sara Jacobs, and many others who worked to persuade Members to pass this bill in such a strong bipartisan victory. Much of the credit also goes to PPSA’s followers, thousands of whom called and emailed Members of the House at a critical time. “We will need you again when the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act goes to the Senate,” Schaerr said. “Stay tuned.” ITI is the big tent tech association with members that rank among America’s most innovative companies, such as Dell, Salesforce, and Texas Instruments. ITI is warning the Senate to strip out language in the Reforming Intelligence and Securing America Act (RISAA) that “vastly expands the U.S. government’s warrantless surveillance capabilities.”

This language was added as an amendment by the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence. It requires “any service provider” or “custodians” with “access to equipment that is being or may be used to transmit or store wire or electronic communications,” to grant the government access to warrantlessly acquired messages. Some on Capitol Hill are questioning if this provision is really as broad as it reads. It is being portrayed by the intelligence community as a technical fix that will allow the NSA to selectively surveil foreign intelligence targets. The ITI and hundreds of other organizations beg to differ. ITI writes that adding “access to equipment” is a monumental change because – from routers and switches to servers and virtual networking gear to the internet and communications that ride on it – all global communications transmission and storage are powered by real-life physical information and communications technology (ICT). And ITI writes “there are tens of thousands of such companies” that use such equipment. “Expanding the definition to ‘any’ service provider by dropping ‘communications’ has equally wide-ranging implications when we factor in the multiplicity of service providers who play a role in helping to transmit or store the ICT communications,” ITI writes. “For example, on its face the amendment would appear to cover data centers, cloud storage providers, co-location providers, managed security services providers and a variety of other companies who provide services underlying or related to ICT communications transmission and storage; or merely those many companies and individuals who have access to the equipment necessary to provide such services – from building and facilities owners/landlords to cleaning/janitorial staff to the many types of commercial entities that provide a WiFi connection to their guests.” (Emphasis added.) Thus, the nation’s most innovation companies validate civil liberties experts who characterize this amendment as the “Everyone’s a Spy” provision. On a final note, ITI writes that this provision complicates the already contentious and complicated efforts of the Biden Administration to comply with the new EU-US Data Privacy Framework. It is hard to imagine that European politicians and EU regulators will not react to this vast expansion of U.S. surveillance, most likely in a protectionist manner that will harm U.S. exports and competitiveness. So take it from the experts – this language is as exactly as expansive as it reads. It is critical for the Senate to remove it before passing the bill. Like a gourmand gorging at a banquet table, the government’s growing appetite for expanding surveillance is beginning to get a little hard watch. Consider some recent developments.

First, the Senate is voting this week on a bill to reauthorize FISA Section 702 with an amendment that includes what Sen. Ron Wyden calls “one of the most dramatic and terrifying expansions of government surveillance authority in history.” This bill would compel millions of small businesses that merely have “access” to “communications equipment” (like Wi-Fi) to hand over customers’ messages to the government. Little wonder this has been branded the “Everyone’s a Spy” provision. Second, the House will also vote on the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, which would curb the practice of the FBI and other federal agencies of purchasing Americans’ most sensitive digital information from data brokers. Third, a House Judiciary Committee investigation also recently found that the U.S. Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) has been working with banks to conduct warrantless dragnets of large numbers of Americans’ confidential financial information, often using politically charged search terms. In all, 650 companies were connected to the FBI’s web port, covering two-thirds of U.S. GDP and 35 million people. See a pattern here? The government’s hunger to expand surveillance into every realm of American life cannot be filled. Many of these programs – like data purchases and FinCEN surveillance – are based on no law and fall under no Congressional or judicial oversight. Now, thanks to former Attorney General William Barr, we know that the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is also getting in on the act. With no statutory approval, the SEC is taking it upon itself to start a huge database called the Consolidated Audit Trail that will allow 3,000 government employees to track, in real time, the identity of tens of millions of Americans who buy and sell stocks and other securities. “This invites abusive investigatory fishing expeditions, targeting of individuals, and intrusive data mining,” Barr writes in The Wall Street Journal. “Concentrating this sensitive data in a single repository guarantees it inevitably will be hacked, stolen, or misused by bad actors.” Barr mostly dwells on the inappropriateness of government surveillance of millions of people who’ve done nothing suspicious. He adds that “the whole point of the Fourth Amendment is to make the government less efficient by making it jump through hoops when it seeks to delve into private affairs. For an agency to argue that it should be able to avoid these hoops to make investigations easier is to assert that it should be exempt from the Fourth Amendment.” Well stated. This is the same William Barr, however, who also recently took the pages of National Review to persuade his fellow conservatives to support the House Intelligence Committee’s version of FISA reauthorization – which also authorizes many forms of dragnet surveillance. Perhaps it will soon dawn on the supporters of the status quo that the “whole point of the Fourth Amendment” should reach beyond stock trades to include “Everyone’s a Spy,” data purchases and all the other egregious privacy violations of our growing surveillance state. Is it fair to call one amendment to the Reforming Intelligence and Securing America Act (RISAA) the “Everyone’s a Spy” provision? This amendment to RISAA now before the Senate would compel a provider of any service, who has “access” to communications equipment, to quietly cooperate with the NSA in collecting messages.

Because the people who work at most ordinary businesses – from fitness centers to commercial office buildings – have no expertise in parsing data, they would likely just hand over all the messages of their customers to the NSA, including countless messages between Americans. Here’s how Sen. Ron Wyden characterized this measure on the Senate floor: “After all, every office building in America has data cables running through it. These people are not just the engineers who install, maintain, and repair our communications infrastructure; there are countless others who could be forced to help the government spy, including those who clean offices and guard buildings. If this provision is enacted, the government could deputize any one of these people against their will and force them to become an agent for Big Brother. “For example, by forcing an employee to insert a USB thumb drive into a server at an office they clean or guard at night. “This could all happen without any oversight. The FISA Court won’t know about it. Congress won’t know about it. The Americans who are handed these directives will be forbidden from talking about it. And unless they can afford high priced lawyers with security clearances who know their way around the FISA Court, they will have no recourse at all.” Sen. Wyden is not writing science-fiction. We’ve seen again and again when the FBI and other federal agencies can find a way to expand a loophole – as with backdoor searches of Section 702 data or the data broker loophole – they will do so. Our digital traces can be put together to tell the stories of our lives. They reveal our financial and health status, our romantic activities, our religious beliefs and practices, and our political beliefs and activities.

Our location histories are no less personal. Data from the apps on our phone record where we go and with whom we meet. Taken all together, our data creates a portrait of our lives that is more intimate than a diary. Incredibly, such information is, in turn, sold by data brokers to the FBI, IRS, the Drug Enforcement Administration, the Department of Defense, the Department of Homeland Security, and other federal agencies to freely access. The Constitution’s Fourth Amendment forbids such unreasonable searches and seizures. Yet federal agencies maintain they have the right to collect and examine our personal information – without warrants. A recent report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence shows that:

The American people are alarmed. Eighty percent of Americans in a recent YouGov poll say Congress should require government agencies to obtain a warrant before purchasing location information, internet records, and other sensitive data about people in the U.S. from data brokers. The Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act now up for a vote in the House would prohibit law enforcement and intelligence agencies from purchasing certain sensitive information from third-party sellers, including geolocation information and communications-related information that is protected under the Electronic Communications Privacy Act, and information obtained from illicit data scraping. This bill balances Americans’ civil liberties with national security, giving law enforcement and intelligence agencies the ability to access this information with a warrant, court order, or subpoena. Call your U.S. House Representative and say: “Please protect my privacy by voting for the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act.” When Members of the House voted last week to reauthorize FISA Section 702, most did not realize that an amendment from the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (HPSCI), sold as a “narrow” definitional change to the law, will actually deliver what Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR) calls “one of the most dramatic and terrifying expansions of government surveillance authority in history.” What the House missed the Senate can still fix. The Senate still has time to perform emergency surgery and excise this particularly toxic amendment. Here’s the background: For years, “electronic communications service providers” such as Verizon or Google’s Gmail have been required to turn over the communications of targets. The House bill expands this requirement to enlist millions of small businesses that provide Wi-Fi or have access to routers or similar communications equipment. This provision would make American small businesses into providers of KGB-like surveillance. If this seems hyperbolic, consider that this HPSCI amendment would force American small businesses of many sorts to collect the communications of their customers for the government. The bill does this by including any service provider who has access to equipment that transmits communications. The language was narrowed to exclude hotels, restaurants, dwellings, and community centers, but the measure still includes most businesses – owners and operators of any facilities that house equipment used to store or carry data, including data centers and commercial office buildings. Millions of Americans, with little or no knowledge of the equipment they own or service –landlords, utility providers, repairmen, plumbers, cleaning contractors, and similar professionals – would have a legal obligation to secretly spy for the government. Lacking any ability to separate the communications of Americans from foreigners, they would be forced either to give the government direct access to the equipment or copy its messages en masse and turn it over. And then they would be under a gag order to keep their snooping a secret. This version of Section 702 reauthorization would be a disaster for small businesses of all sorts. Bound to silence, small businesses would suffer consumer distrust as public knowledge of the contamination of the data supply chain spread. Consumers and business would have no recourse. This bill also marks a terrifying replacement of the constitutional order under the Fourth Amendment. For these reasons, the Senate must do its duty and remove it. Call Your Senators: |

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed