|

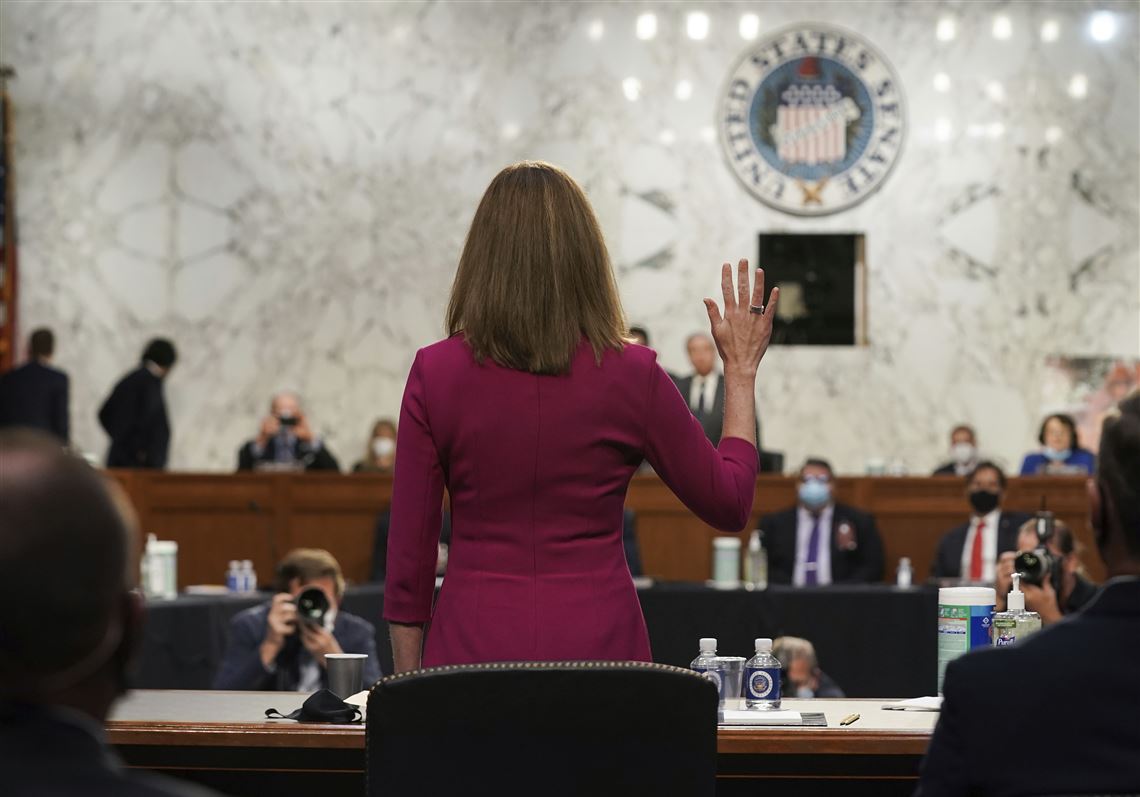

Yesterday morning, we reviewed Judge Amy Coney Barrett’s Seventh Circuit decisions for hints as to how she might vote as a Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court in cases related to surveillance law and privacy. A subsequent exchange with Sen. Ben Sasse, R-NE, gave us a greater insight into her thinking on the Fourth Amendment – which appears to be similar to that of her mentor, the late Justice Antonin Scalia, as well as the justice she has been nominated to replace, the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Sen. Sasse, in exploring Judge Barrett’s thinking on the judicial philosophy of originalism, delved into the question of how 18th century language – such as the text of the Fourth Amendment – can resolve questions involving modern technology. He asked: “Does the Fourth Amendment have nothing to say about cell phones and reasonable search and seizure? [It] was obviously not written at a time when they had imagined mobile technological devices that addicted our kids. Does the Fourth Amendment have nothing to say about cellphones?” Judge Barrett answered: The Constitution, one reason why it’s the longest lasting written constitution in the world, is because it’s written at a level of generality that’s specific enough to protect rights, but general enough to be lasting. So that … when you’re talking about the constable banging at your door in 1791 as a search or seizure, now we can apply it as the court did in Carpenter v. United States to cellphones. So the Fourth Amendment is a principle. It protects against unreasonable searches and seizures, but it doesn’t catalogue the instances in which an unreasonable search or seizure could take place. So you take that principle, and then you apply it to modern technology, like cell phones … Or what if technological advances enable someone with Superman X-ray vision to simply see in your house, so there’s no need to knock on your door to go in? Well I think that could still be analyzed under the Fourth Amendment.” She later said: [A]s I said with the Fourth Amendment, many of [the Constitution’s] principles are more general: unreasonable searches and seizures, free speech. These are things that have to be identified or fleshed out, applied over time. So the fact that there wasn’t the internet or computers or blogs in 1791 doesn’t mean that the First Amendment’s Free Speech Clause wouldn’t apply to those things now. It enshrines a principle … that is capable of being applied to new circumstances.” Under questioning from Sen. Marsha Blackburn, R-TN, about the applications of the Fourth Amendment, Judge Barrett favorably cited Justice Scalia’s reasoning in Kyllo v. United States (2001). In this case, a man accused of growing marijuana was targeted for prosecution after the police used infrared, thermal imaging technology to identify increased power use in his home. A 5-4 majority in that case – including Scalia’s friend, Justice Ginsburg – held that thermal imaging constituted a search and should have required a warrant. “The late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg had similarly sided with the majority in restricting the ability of the government to track Americans’ cellphone location history without a warrant,” said Gene Schaerr, PPSA general counsel. “Judge Amy Coney Barrett’s answers today indicate that she would likely follow in the footsteps of Justices Ginsburg and Scalia as another champion of the Fourth Amendment.” Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed