|

A federal court has given the go-ahead for a lawsuit filed by Just Futures Law and Edelson PC against Western Union for its involvement in a dragnet surveillance program called the Transaction Record Analysis Center (TRAC).

Since 2022, PPSA has followed revelations on a unit of the Department of Homeland Security that accesses bulk data on Americans’ money wire transfers above $500. TRAC is the central clearinghouse for this warrantless information, recording wire transfers sent or received in Arizona, California, New Mexico, Texas, and Mexico. These personal, financial transactions are then made available to more than 600 law enforcement agencies – almost 150 million records – all without a warrant. Much of what we know about TRAC was unearthed by a joint investigation between ACLU and Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR). In 2023, Gene Schaerr, PPSA general counsel, said: “This purely illegal program treats the Fourth Amendment as a dish rag.” Now a federal judge in Northern California determined that the plaintiffs in Just Future’s case allege plausible violations of California laws protecting the privacy of sensitive financial records. This is the first time a court has weighed in on the lawfulness of the TRAC program. We eagerly await revelations and a spirited challenge to this secretive program. The TRAC intrusion into Americans’ personal finances is by no means the only way the government spies on the financial activities of millions of innocent Americans. In February, a House investigation revealed that the U.S. Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) has worked with some of the largest banks and private financial institutions to spy on citizens’ personal transactions. Law enforcement and private financial institutions shared customers’ confidential information through a web portal that connects the federal government to 650 companies that comprise two-thirds of the U.S. domestic product and 35 million employees. TRAC is justified by being ostensibly about the border and the activities of cartels, but it sweeps in the transactions of millions of Americans sending payments from one U.S. state to another. FinCEN set out to track the financial activities of political extremists, but it pulls in the personal information of millions of Americans who have done nothing remotely suspicious. Groups on the left tend to be more concerned about TRAC and groups on the right, led by House Judiciary Chairman Jim Jordan, are concerned about the mass extraction of personal bank account information. The great thing about civil liberties groups today is their ability to look beyond ideological silos and work together as a coalition to protect the rights of all. For that reason, PPSA looks forward to reporting and blasting out what is revealed about TRAC in this case in open court. Any revelations from this case should sink in across both sides of the aisle in Congress, informing the debate over America’s growing surveillance state. The reform coalition on Capitol Hill remains determined to add strong amendments to Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). But will they get the chance before an April 19th deadline for FISA Section 702’s reauthorization?

There are several possible scenarios as this deadline closes. One of them might be a vote on the newly introduced “Reforming Intelligence and Securing America” (RISA) Act. This bill is a good-faith effort to represent the narrow band of changes that the pro-reform House Judiciary Committee and the status quo-minded House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence could agree upon. But is it enough? RISA is deeply lacking because it leaves out two key reforms.

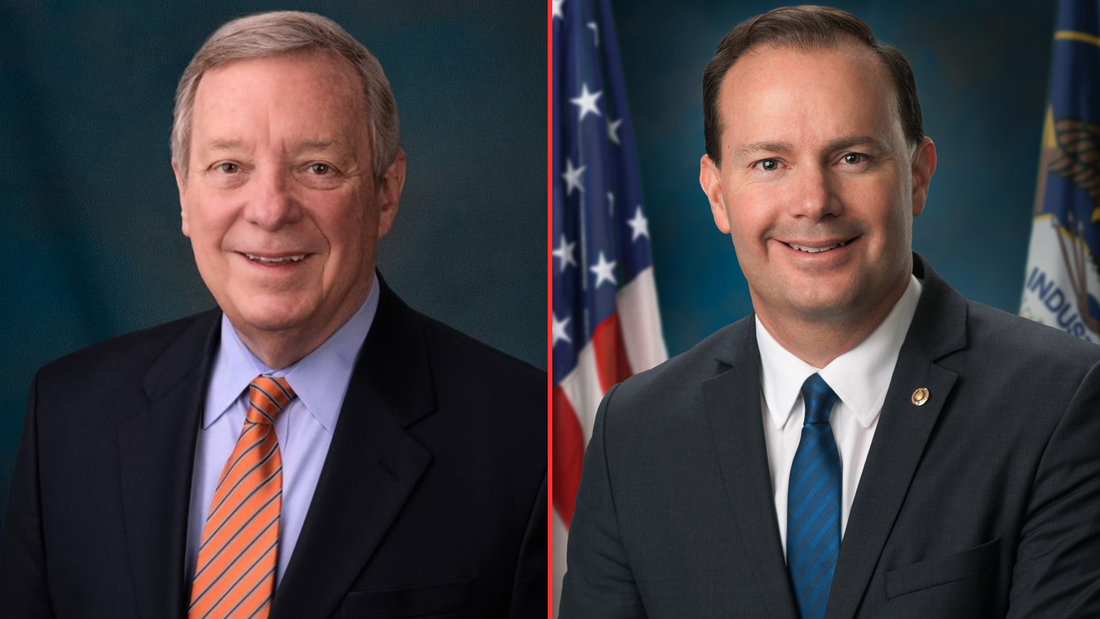

The bill does include a role for amici curiae, specialists in civil liberties who would act as advisors to the secret FISA court. RISA, however, would limit the issues these advisors could address, well short of the intent of the Senate when it voted 77-19 in 2020 to approve the robust amici provisions of the Lee-Leahy amendment. For all these reasons, reformers should see RISA as a floor, not as a ceiling, as the Section 702 showdown approaches. The best solution to the current impasse is to stop denying Members of Congress the opportunity for a straight up-or-down vote on reform amendments. The contest between surveillance reformers and defenders of domestic surveillance is set to come to a showdown in the second week of April. Speaker Mike Johnson told Politico that his “current plan is to run FISA as a standalone the week after Easter.” Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) allows federal agencies to gather foreign intelligence but has been used by the government to conduct domestic surveillance on millions of Americans in recent years. Its reauthorization, with or without reforms, will almost certainly come to a vote before its expiration on April 19. The big question is whether the House will be allowed vote on two reform amendments. These amendments would impose warrant requirements before federal agencies could inspect the communications of Americans caught up in the global trawl of intelligence agencies, as well as for the sensitive, personal information of Americans scraped by apps and sold by data brokers to the government. These amendments are backed by strong bipartisan support that spans across the aisle and includes leaders of the Freedom and Progressive caucuses. The odds of votes on reform amendment on the House floor increased with renewed pressure for reform coming from the Senate. Sens. Dick Durbin (D-IL) and Mike Lee (R-UT) introduced the Security and Freedom Enhancement (SAFE) Act, which includes the prime provisions of House reformers, with a few pragmatic concessions to the needs of intelligence practitioners. The route to this moment has been long and tortuous. The House reauthorization bill, and a chance to vote on the two warrant amendments, was pulled at the request of the intelligence community in February when it became clear these measures likely had majority support. With powerful bipartisan support for reform now coming from two respected lawmakers on the Senate Judiciary Committee, it will be hard to stiff-arm reformers again in either chamber. That doesn’t mean it cannot happen. Expect the champions of the surveillance status quo to come up with new legislative tricks and scares (remember the Putin space nuke debacle?) before April’s vote. PPSA will be tracking every development in this struggle. Registering your determination for surveillance reform now will help maintain the “current plan” for reauthorization, debate, and vote on reform amendments. Tell your U.S. House Representative:“Stop the FBI and other government agencies from spying on innocent Americans. Please fight for a vote to reform FISA’s Section 702 with warrant requirements, both for Section 702 data and for our sensitive, personal information sold to the government by data brokers.” The best intentions of Amazon to reduce easy, warrantless surveillance of the American people are being undermined by cheap, Chinese cameras.

PPSA has long tracked the privacy threat of Amazon’s cooperative agreements with more than 2,000 police and fire departments to solicit Ring videos for neighborhood surveillance from customers. In January, we celebrated Amazon’s disabling of its Request for Access tool, a feature that facilitated requests from law enforcement to ask Ring camera owners to volunteer video of their neighbors and neighborhood. The Electronic Frontier Foundation was so impressed by Amazon’s move that they removed Ring from its Atlas of Surveillance, a comprehensive, national map of points of police surveillance. In March, EFF removed 2,530 data points from its Atlas because Amazon will no longer facilitate warrantless requests for consumer video footage. As EFF notes, this does not mean that the police won’t still be able to access Ring footage. PPSA reported in February that law enforcement in central Texas are ho-hum about Amazon’s policy change, telling reporters they will simply appeal to individual households to ask for videos. But at least this means police requests will be tied to actual events, requiring an expenditure of shoe leather after a burglary, car accident, or fire, instead of a broad array of surveillance footage available for police to examine. Around the same time, journalists Stacey Higginbotham and Daniel Wroclawski of Consumer Reports (CR) demonstrated the alarming vulnerability of cheap, Chinese doorbell cameras sold by Amazon, as well as by Walmart, Sears, and Chinese online retailers Shein and Temu. These cameras are sold by the thousands under an ever-shifting array of brand names, but all are connected to the same app called Awit, owned by Shenzen-based Eken Group Ltd., and apparently managed in North America out of an apartment in east Los Angeles County. Higginbotham and Wroclawski reported that with the use of the Awit app, these cameras were easily compromised and used for remote surveillance of their owners – the exact opposite of the purpose of a security camera. They wrote: “People who face threats from a stalker or estranged abusive partner are sometimes spied on through their phones, online platforms, and connected smartphone devices. The vulnerabilities CR found could allow a dangerous person to take control of the video doorbell on their target’s home, watching when they and their family members come and go.” Worse, these doorbells expose their owners’ home IP address and Wi-Fi network name to the internet without encryption. They also lack a visible ID issued by the Federal Communications Commission, making them illegal to sell in the United States. Weeding out junk products is probably a difficult task for Amazon, given the shape-shifting, brand-changing nature of some providers. Like many Chinese-made products, these doorbell cameras are booby-trapped, either through sloppiness or by intention, or perhaps both. It doesn’t take a lot of imagination to envision them being used against U.S. officials, civilian or military, by Chinese intelligence during a crisis. Imagine the intelligence value of seeing National Security Council personnel leaving their homes at the same time around 2 a.m. Amazon’s top search results showed few of these Chinese cameras available now, though it is hard to tell given the plethora of ever-changing brand names. Perhaps Amazon products should come with a cautionary “China” sticker for consumers. Our general counsel, Gene Schaerr, explains in the Washington Examiner how the Biden administration's recent executive order to protect personal data from government abuse falls short. Hint: It excludes our very own government's abuse of our personal data.

The reauthorization of FISA Section 702, which allows federal agencies to conduct international surveillance for national security purposes, has languished in Congress like an old Spanish galleon caught in the doldrums. This happened after opponents of reform pulled Section 702 reauthorization from the House floor rather than risk losing votes on popular measures, such as requiring government agencies to obtain warrants before surveilling Americans’ communications.

But the winds are no longer becalmed. They are picking up – and coming from the direction of reform. Sen. Dick Durbin (D-IL), Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, and fellow committee member Sen. Mike Lee (R-UT), today introduced the Security and Freedom Enhancement (SAFE) Act. This bill requires the government to obtain warrants or court orders before federal agencies can access Americans’ personal information, whether from Section 702-authorized programs or purchased from data brokers. Enacted by Congress to enable surveillance of foreign targets in foreign lands, Section 702 is used by the FBI and other federal agencies to justify domestic spying. According to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) Court, under Section 702 government “batch” searches have included a sitting U.S. Congressman, a U.S. Senator, journalists, political commentators, a state senator, and a state judge who reported civil right violations by a local police chief to the FBI. It has even been used by government agents to stalk online romantic prospects. Millions of Americans in recent years have had their communications compromised by programs under Section 702. The reforms of the SAFE Act promise to reverse this trend, protecting Americans’ privacy and constitutional rights from the government. The SAFE Act requires:

Durbin-Lee is a pragmatic bill. It lifts warrants and other requirements in emergency circumstances. The SAFE Act allows the government to obtain consent for surveillance if the subject of the search is a potential victim or target of a foreign plot. It allows queries designed to identify targets of cyberattacks, where the only content accessed and reviewed is malicious software or cybersecurity threat signatures. The SAFE Act is a good-faith effort to strike a balance between national security and Americans’ privacy. It should break the current stalemate, renewing the push for debate and votes on amendments to the reauthorization of Section 702. How to Tell if You are Being Tracked Car companies are collecting massive amounts of data about your driving – how fast you accelerate, how hard you brake, and any time you speed. These data are then analyzed by LexisNexis or another data broker to be parsed and sold to insurance companies. As a result, many drivers with clean records are surprised with sudden, large increases in their car insurance payments.

Kashmir Hill of The New York Times reports the case of a Seattle man whose insurance rates skyrocketed, only to discover that this was the result of LexisNexis compiling hundreds of pages on his driving habits. This is yet another feature of the dark side of the internet of things, the always-on, connected world we live in. For drivers, internet-enabled services like navigation, roadside assistance, and car apps are also 24-7 spies on our driving habits. We consent to this, Hill reports, “in fine print and murky privacy policies that few read.” One researcher at Mozilla told Hill that it is “impossible for consumers to try and understand” policies chocked full of legalese. The good news is that technology can make data gathering on our driving habits as transparent as we are to car and insurance companies. Hill advises:

What you cannot do, however, is file a report with the FBI, IRS, the Department of Homeland Security, or the Pentagon to see if government agencies are also purchasing your private driving data. Given that these federal agencies purchase nearly every electron of our personal data, scraped from apps and sold by data brokers, they may well have at their fingertips the ability to know what kind of driver you are. Unlike the private snoops, these federal agencies are also collecting your location histories, where you go, and by inference, who you meet for personal, religious, political, or other reasons. All this information about us can be accessed and reviewed at will by our government, no warrant needed. That is all the more reason to support the inclusion of the principles of the Fourth Amendment Is Not for Sale Act in the reauthorization of the FISA Section 702 surveillance policy. Does the intelligence community have a secret veto?Time and again, the forces of the surveillance status quo have prevented Congress from voting on reforms of FISA Section 702 – the authority passed by Congress to allow the government to track foreign threats but has been used in recent years to surveil millions of ordinary Americans.

The intelligence community especially doesn’t want Congress to demand closure of the loophole that allows the government to purchase your most sensitive and personal information from data brokers. Federal agencies can use this data to accumulate a portfolio of your health and medical issues, personal life, financial concerns, religious beliefs and worship, and political posts and activities. Repeated attempts by the U.S. House of Representatives to debate and hold a floor vote on these reform amendments to Section 702 have been stalled by legislative maneuvers and gamesmanship. At the same time, the government has applied to the FISA Court to extend Section 702 without reforms for a whole year, which could elbow Congress out of the policy process entirely. While Congress struggles, a poll conducted by YouGov, commissioned by FreedomWorks and DemandProgress, show the American people – Republicans, Democrats, and independents – are paying attention and they do not like what they see:

In the reauthorization of Section 702, Americans demand that Congress:

Members of Congress are now asking themselves: If I allow these domestic surveillance programs to continue, how am I going to explain this my constituents? You can help clarify this issue for your Member of Congress. Tell your U.S. House Representative: “Stop the FBI and other government agencies from spying on innocent Americans. Please fight for a vote to reform FISA’s Section 702 with warrant requirements, both for Section 702 data and for our sensitive, personal information sold to the government by data brokers.” While Congress debates adding reforms to FISA Section 702 that would curtail the sale of Americans’ private, sensitive digital information to federal agencies, the Federal Trade Commission is already cracking down on companies that sell data, including their sales of “location data to government contractors for national security purposes.”

The FTC’s words follow serious action. In January, the FTC announced proposed settlements with two data aggregators, X-Mode Social and InMarket, for collecting consumers’ precise location data scraped from mobile apps. X-Mode, which can assimilate 10 billion location data points and link them to timestamps and unique persistent identifiers, was targeted by the FTC for selling location data to private government contractors without consumers’ consent. In February, the FTC announced a proposed settlement with Avast, a security software company, that sold “consumers’ granular and re-identifiable browsing information” embedded in Avast’s antivirus software and browsing extensions. What is the legal basis for the FTC’s action? The agency seems to be relying on Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act, which grants the FTC power to investigate and prevent deceptive trade practices. In the case of X-Mode, the FTC’s proposed complaint highlight’s X-Mode’s statement that their location data would be used solely for “ad personalization and location-based analytics.” The FTC alleges X-Mode failed to inform consumers that X-Mode “also sold their location data to government contractors for national security purposes.” The FTC’s evolving doctrine seems even more expansive, weighing the stated purpose of data collection and handling against its actual use. In a recent blog, the FTC declares: “Helping people prepare their taxes does not mean tax preparation services can use a person’s information to advertise, sell, or promote products or services. Similarly, offering people a flashlight app does not mean app developers can collect, use, store, and share people’s precise geolocation information. The law and the FTC have long recognized that a need to handle a person’s information to provide them a requested product or service does not mean that companies are free to collect, keep, use, or share that’s person’s information for any other purpose – like marketing, profiling, or background screening.” What is at stake for consumers? “Browsing and location data paint an intimate picture of a person’s life, including their religious affiliations, health and medical conditions, financial status, and sexual orientation.” If these cases go to court, the tech industry will argue that consumers don’t sign away rights to their private information when they sign up for tax preparation – but we all do that routinely when we accept the terms and conditions of our apps and favorite social media platforms. The FTC’s logic points to the common understanding that our data is collected for the purpose of selling us an ad, not handing over our private information to the FBI, IRS, and other federal agencies. The FTC is edging into the arena of the Fourth Amendment Is Not for Sale Act, which targets government purchases and warrantless inspection of Americans’ personal data. The FTC’s complaints are, for the moment, based on legal theory untested by courts. If Congress attaches similar reforms to the reauthorization of FISA Section 702, it would be a clear and hard to reverse protection of Americans’ privacy and constitutional rights. Ken Blackwell, former ambassador and mayor of Cincinnati, has a conservative resume second to none. He is now a senior fellow of the Family Research Council and chairman of the Conservative Action Project, which organizes elected conservative leaders to act in unison on common goals. So when Blackwell writes an open letter in Breitbart to Speaker Mike Johnson warning him not to try to reauthorize FISA Section 702 in a spending bill – which would terminate all debate about reforms to this surveillance authority – you can be sure that Blackwell was heard.

“The number of FISA searches has skyrocketed with literally hundreds of thousands of warrantless searches per year – many of which involve Americans,” Blackwell wrote. “Even one abuse of a citizen’s constitutional rights must not be tolerated. When that number climbs into the thousands, Congress must step in.” What makes Blackwell’s appeal to Speaker Johnson unique is he went beyond including the reform efforts from conservative stalwarts such as House Judiciary Committee Chairman Jim Jordan and Rep. Andy Biggs of the Freedom Caucus. Blackwell also cited the support from the committee’s Ranking Member, Rep. Jerry Nadler, and Rep. Pramila Jayapal, who heads the House Progressive Caucus. Blackwell wrote: “Liberal groups like the ACLU support reforming FISA, joining forces with conservatives civil rights groups. This reflects a consensus almost unseen on so many other important issues of our day. Speaker Johnson needs to take note of that as he faces pressure from some in the intelligence community and their overseers in Congress, who are calling for reauthorizing this controversial law without major reforms and putting that reauthorization in one of the spending bills that will work its way through Congress this month.” That is sound advice for all Congressional leaders on Section 702, whichever side of the aisle they are on. In December, members of this left-right coalition joined together to pass reform measures out of the House Judiciary Committee by an overwhelming margin of 35 to 2. This reform coalition is wide-ranging, its commitment is deep, and it is not going to allow a legislative maneuver to deny Members their right to a debate. U.S. Treasury and FBI Targeted Americans for Political BeliefsThe House Judiciary Committee and its Select Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Federal Government issued a report on Wednesday revealing secretive efforts between federal agencies and U.S. private financial institutions that “show a pattern of financial surveillance aimed at millions of Americans who hold conservative viewpoints or simply express their Second Amendment rights.”

At the heart of this conspiracy is the U.S. Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) and the FBI, which oversaw secret investigations with the help of the largest U.S. banks and financial institutions. They did not lack for resources. Law enforcement and private financial institutions shared customers’ confidential information through a web portal that connects the federal government to 650 companies that comprise two-thirds of the U.S. domestic product and 35 million employees. This dragnet investigation grew out of the aftermath of the Jan. 6 riot in the U.S. Capitol, but it quickly widened to target the financial transactions of anyone suspiciously MAGA or conservative. Last year we reported on how the Bank of America volunteered the personal information of any customer who used an ATM card in the Washington, D.C., area around the time of the riot. In this newly revealed effort, the FBI asked financial services companies to sweep their database to look for digital transactions with keywords like “MAGA” and “Trump.” FinCEN also advised companies how to use Merchant Category Codes (MCC) to search through transactions to detect potential “extremists.” Keywords attached to suspicious transactions included recreational stores Cabela’s, Bass Pro Shop, and Dick’s Sporting Goods. The committee observed: “Americans doing nothing other than shopping or exercising their Second Amendment rights were being tracked by financial institutions and federal law enforcement.” FinCEN also targeted conservative organizations like the Alliance Defending Freedom or the Eagle Forum for being demonized by a left-leaning organization, the Institute for Strategic Dialogue in London, as “hate groups.” The committee report added: “FinCEN’s incursion into the crowdfunding space represents a trend in the wrong direction and a threat to American civil liberties.” One doesn’t have to condone the breaching of the Capitol and attacks on Capitol police to see the threat of a dragnet approach that lacked even a nod to the concept of individualized probable cause. What was done by the federal government to millions of ordinary American conservatives could also be done to millions of liberals for using terms like “racial justice” in the aftermath of the riots that occurred after the murder of George Floyd. These dragnets are general warrants, exactly the kind of sweeping, indiscriminate violations of privacy that prompted this nation’s founders to enact the Fourth Amendment. If government agencies cannot satisfy the low hurdle of probable cause in an application for a warrant, they are apt to be making things up or employing scare tactics. If left uncorrected, financial dragnets like these will support a default rule in which every citizen is automatically a suspect, especially if the government doesn’t like your politics. The growth of the surveillance state in Washington, D.C., is coinciding with a renewed determination by federal agencies to expose journalists’ notes and sources. Recent events show how our Fourth Amendment right against unreasonable searches and seizures and our First Amendment right of a free press are inextricable and mutually reinforcing – that if you degrade one of these rights, you threaten both of them.

In May, the FBI raided the home of journalist Tim Burke, seizing his computer, hard drives, and cellphone, after he reported on embarrassing outtakes of a Fox News interview. It turns out these outtakes had already been posted online. Warrants were obtained, but on what credible allegation of probable cause? Or consider CBS News senior correspondent Catherine Herridge who was laid off, then days later ordered by a federal judge to reveal the identity of a confidential source she used for a series of 2017 stories published while she worked at Fox News. Shortly afterwards, Herridge was held in contempt for refusing to divulge that source. This raises the question that when CBS had earlier terminated Herridge and seized her files, would network executives have been willing to put their freedom on the line as Herridge has done? In response to public outcry, CBS relented and handed Herridge’s notes back to her. But local journalists cannot count on generating the national attention and sympathy that a celebrity journalist can. Now add to this vulnerability the reality that every American who is online – whether a national correspondent or a college student – has his or her sensitive and personal information sold to more than a dozen federal agencies by data brokers, a $250 billion industry that markets our data in the shadows. The sellers of our privacy compile nearly limitless data dossiers that “reveal the most intimate details of our lives, our movements, habits, associations, health conditions, and ideologies.” Data brokers have established a sophisticated system to aggregate data from nearly every platform and device that records personal information to develop detailed profiles on individuals. To fill in the blanks, they also sweep up information from public records. So if you have a smartphone, apps, or search online, your life is already an open book to the government. In this way, state and federal intelligence and law enforcement agencies can use the data broker loophole to obtain information about Americans that they would otherwise need a warrant, court order, or subpoena to obtain. Now imagine what might happen as these two trends converge – a government hungry to expose journalists’ sources, but one that also has access to a journalist’s location history, as well as everyone they have called, texted, and emailed. It is hardly paranoid, then, to worry that when a prosecutor tries to compel a journalist to give up a source through legal means, purchased data may have already given the government a road map on what to seek. The combined threat to privacy from pervasive surveillance and prosecutors seeking journalists’ notes is serious and growing. This is why PPSA supports legislation to protect journalistic privacy and close the data broker loophole. The Protect Reporters from Exploitive State Spying, or PRESS Act, would grant a privilege to protect confidential news sources in federal legal proceedings, while offering reasonable exceptions for extreme situations. Such “shield laws” have been put into place in 49 states. The PRESS Act, which passed the House in January with unanimous, bipartisan support, would bring the federal government in line with the states. Likewise, the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act would close the data broker loophole and require the government to obtain a warrant before it can seize our personal information, as required by the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. The House Judiciary Committee voted to advance the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act out of committee with strong bipartisan support in July. The Judiciary Committee also reported out a strong data broker loophole closure as part of the Protect Liberty Act in December. Now, it’s up to Congress to include these protection and reform measures in the reauthorization of Section 702. PPSA urges lawmakers to pass measures to protect privacy and a free press. They will rise or fall together. The Biden Administration has placed the people, the industry, and the national security of the United States on the edge of a cyber cliff and is threatening to push us all off.

Does that sound alarmist? Consider: Wikipedia brings together thousands of volunteers to curate a free, online encyclopedia about – well, everything – including the policies and personalities of repressive, homicidal regimes from Russia, to China, to North Korea. In the last decade, the Wikimedia Foundation, the non-profit that hosts Wikipedia, has received increasing requests to provide user data to governments and wealthy individuals. These foreign appeals not only seek to bowdlerize accurate information and censor editorial content, they also ask for personal data to enable retaliation against the volunteers who edit Wikipedia. On one level, this is actually kind of funny. Dictators and cartel bosses who rule by terror at home are reduced to making polite requests to the Wikimedia Foundation because the current system denies them local access to Wikipedia data. The architecture of an open internet, which forbids forced data localization, thus throws up roadblocks for malevolent foreign interests that would access Americans’ online, personal information. Now Americans’ privacy and the security of U.S. data is completely at risk because of U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai’s astonishing withdrawal of support for the underpinnings of a global internet before the World Trade Organization. Tai’s move leaves the Biden Administration moving in opposite directions at once. With one hand, the Biden Administration recently issued an executive order cracking down on the sale of Americans’ personal data by data brokers to foreign “countries of concern.” With the other hand – the president’s trade representative – the U.S. offered to drop its long-standing opposition to forced data localization and to forced transfers of American tech companies’ algorithms to governments around the world. Tai would hand the keys to America’s digital kingdom to more than 80 countries, including China. It is not only Americans who will be at risk, but political dissidents and religious minorities around the world. “Growing requirements for data localization are happening alongside a global crackdown on free expression,” wrote the American Civil Liberties Union, the Center for Democracy & Technology, Freedom House, Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, Internet Society, PEN America, and the Wikimedia Foundation. “And people’s personal data – which can reveal who they voted for, who they worship, and who they love – can help facilitate this … 78 percent of the world’s internet users live in countries where simply expressing political, social, and religious viewpoints leads to legal repercussions.” The Biden Administration’s forced disclosure of source codes will undermine the national and personal security of our country. Why? And for what? We are not sure, but it is clear that it would put all Americans’ privacy and personal security at risk. China is planning to build a large base on the moon in the 2030s, with science labs, housing for astronauts, and a fleet of robots. It is also planning to bring up the advanced technologies that enable its 600-million camera Skynet system to surveil the Chinese people.

“Skynet” is, of course, familiar to American ears as the AI villain in the Terminator movies. It is also the actual term China uses in English for its surveillance network, a term deriving from an ancient Chinese proverb that includes the line, “There is forever a net in the sky.” Stephen Chen of the South China Morning Post informs us that the meaning here is that those who do wrong or resist the regime will not escape the celestial net. China’s experience with the Skynet system, which fields two cameras for every Chinese adult, has taught the regime how to manage such amounts of surveillance data. This knowledge will be useful in building out a Skynet for the moon. The purpose, say Chinese aerospace agencies, is to create a massive video surveillance system that is “capable of identifying, locating, tracking and aiming at suspicious targets independently.” If so, perhaps the moon really will be looking down on us. PPSA, in concert with a coalition of major civil liberties groups from the left, right, and center, is appealing to Members of Congress “to oppose any legislative end-run that allows the FBI and other intelligence agencies to continue to spy on Americans without giving Congress the opportunity to vote on reforms.”

The word from Capitol Hill is that the intelligence community is now lobbying to attach a reauthorization of FISA Section 702 to a “must-pass” spending measure. Such a maneuver would cement the intelligence community’s strategy of denying Members of Congress a chance to have a debate and to vote on reforms to this surveillance authority. Our letter, which includes Americans for Prosperity, the Brennan Center for Justice, Demand Progress, FreedomWorks, and the Wikimedia Foundation, warns Congress: “The Fourth Amendment will become a constitutional dead letter if the government can continue to track our every movement, communications, where we worship, our financial and health issues, what we believe, and our political activity without warrants.” Our letter concludes: “Congress must be able to vote on reforms rather than being faced with a ‘take-it-or-leave-it’ choice between funding the government and protecting Americans’ liberties.” Our FISA Reform Coalition letter ended by urging Congress to stand up for Americans’ privacy, the Constitution, and against the insulting premise that Members of Congress should not be allowed to vote on surveillance reform. Tell your Representative in the U.S. House that you want the FBI and other federal intelligence agencies to stop spying on you and your family.

In recent years, the FBI and other agencies have freely dipped into Americans’ private communications and data caught up in foreign surveillance. The FBI, IRS, Drug Enforcement Administration, Pentagon, and other agencies also track your every move by purchasing your geolocation data and other sensitive, personal information scraped from the apps on your cellphone and sold to the government by shady data brokers. Your personal information from these sources tells the FBI where you’ve been and where you’re going, where you worship, who you date or have fun with, and all about your health, financial information, personal beliefs, and political activities. Do you trust this government to have so much power over your life? Consider that the FBI has already been caught dipping into Americans’ personal communications in recent years by the millions. The government has followed our political and religious activities for years without warrants, spied on 19,000 donors to a Congressional campaign, and spied on a state senator, a state judge, a U.S. Congressman, and U.S. Senator. If judges and Members of Congress can have their rights violated, imagine how much respect the FBI and other government agencies have for your privacy. For now, champions of the intelligence community on Capitol Hill have used a legislative maneuver to prevent a vote that would require the government to get warrants before looking at your private information. The FBI and their friends know that if these amendments get a fair vote on the House floor, they will lose. So they’ve upended the whole process. This is dirty pool. The lack of a vote denies your Member of Congress the right to debate and vote for reform. Unchallenged, this maneuver ensures that the FBI and other agencies will continue to ignore the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which clearly mandates that the government go to a court and obtain a warrant before your personal communications can be inspected. So tell your U.S. House Representative to demand that the FBI and other federal agencies stop accessing your private, personal communications and data without a warrant. Tell your U.S. House Representative: “Stop the FBI from spying on innocent Americans. Please fight for a vote to reform FISA’s Section 702 with warrant requirements, both for Section 702 data and for our sensitive, personal information sold to the government by data brokers.” On Thursday, the Cato Institute filed a motion in federal court that would compel the Department of Justice to release internal audits of the FISA Section 702 program.

The timing is critical. Cato senior fellow Patrick Eddington is asking the court to release these audits soon, by March 29 at the latest, so these audits can inform the Congressional debate on the reauthorization of FISA Section 702. That statute, which authorizes surveillance on foreign targets but has been used to justify millions of acts of domestic surveillance in recent years, must be reauthorized by April 19. DOJ does release summaries of these audits, but they are terse and without much detail. The full texts of the internal DOJ audits remain secret from both the American people and their elected representatives. A long-standing Freedom of Information Act request for these records filed by Cato has languished since last June. Cato’s filing now communicates a sense of urgency to the court. “American citizens and Congress have no way of comparing DOJ claims about alleged reductions in violations with what the original audits themselves reveal about those violations,” Eddington wrote on a Cato blog. PPSA applauds Cato and Patrick Eddington for taking the initiative. We urge the U.S. District Court of the District of Columbia to expedite the release of these audits in time to inform the debate – doing so out of respect for Congress and the American people. When we covered a Michigan couple suing their local government for sending a drone over their property to prove a zoning violation, we asked if there are any legal limits to aerial surveillance of your backyard.

In this case before the Michigan Supreme Court, Maxon v. Long Lake Township, counsel for the local government said that the right to inspect our homes goes all the way to space. He described the imaging capability of Google Earth satellites, asking: “If you want to know whether it’s 50 feet from this house to this barn, or 100 feet from this house to this barn, you do that right on the Google satellite imagery. And so given the reality of the world we live in, how can there be a reasonable expectation of privacy in aerial observations of property?” One justice reacted to the assertion that if Google Earth could map a backyard as closely and intimately as a drone, that would be a search. “Technology is rapidly changing,” the justice responded. “I don’t think it is hard to predict that eventually Google Earth will have that capacity.” Now William J. Broad of The New York Times reports that we’re well beyond Google Earth’s imaging of barns and houses. Try dinner plates and forks. Albedo Space of Denver is making a fleet of 24 small, low orbit satellites that will use imagery to guide responders in disasters, such as wildfires and other public emergencies. It will improve the current commercial standard of satellite imaging from a focal length of about a foot to about four inches. A former CIA official with decades of satellite experience told Broad that it will be a “big deal” when people realize that anything they are trying to hide in their backyards will be visible. Skinny-dipping in the pool will only be for the supremely confident. To his credit, Albedo chief Topher Haddad said, “we’re acutely aware of the privacy implications,” promising that management will be selective in their choice of clients on a case-by-case basis. It is good to know that Albedo likely won’t be using its technology to catch zone violators or backyard sunbathers. We’ve seen, however, that what is cutting-edge technology today will be standard tomorrow. This is just one more way in which the velocity of technology is outpacing our ability to adjust. There is, of course, one effective response. We can reject the Michigan town’s counsel argument who said, essentially, that privacy’s dead and we should just get over it. Courts and Congress should define orbital and aerial surveillance as searches requiring a probable cause warrant, as defined by the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, before our homes and backyards can be invaded by eyes from above. The greatest danger to privacy is not that Albedo will allow government snoops to watch us in real time. The real threat is a satellite company’s ability to collect private images by the tens of millions. Such a database could then be sold to the government just as so much commercial digital information is now being sold to the government by data brokers. This is all the more reason for Congress to import the privacy-protecting warrant provisions of the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act into the reauthorization of FISA Section 702. In the last century, the surveillance state was held back by the fact that there could never be enough people to watch everybody. Whether Orwell’s fictional telescreens or the East German Stasi’s apparatus of civilian informants, there could simply never be enough watchers to follow every dissident, while having even more people to put all the watcher’s information together (although the Stasi’s elaborate filing system came as close as humanly possible to omniscience).

Now, of course, AI can do the donkey work. It can decide when a face, or a voice, a word, or a movement, is significant and flag it for a human intelligence officer. AI can weave data from a thousand sources – cell-site simulators, drones, CCTV, purchased digital data, and more – and thereby transform data into information, and information into actionable intelligence. The human and institutional groundwork is already in place to feed AI with intelligence from local, national, and global sources in more than 80 “fusion centers” around the country. These are sites where the National Counterterrorism Center coordinate intelligence from the 17 federal intelligence agencies with local and state law enforcement. FBI, NSA, and Department of Homeland Security intelligence networks get mixed in with intelligence from the locals. If you’ve ever reported something suspicious to the “if you see something, say something” ads, a fusion center is where your report goes. With terrorists and foreign threats ever present, it makes sense to share intelligence between agencies, both national and local. But absent clear laws and constitutional limits, we are also building the basics of a full-fledged surveillance state. With no warrant requirements currently in place for federal agencies to inspect Americans’ purchased digital data, there is nothing to stop the fusion of global, national, and local intelligence from a thousand sources into one ever-watchful eye. Step by step, day by day, new technologies, commercial entities and government agencies add new sources and capabilities to this ever-present surveillance. The latest thread in this weave comes from Axon, the maker of Tasers and body cameras for police. Axon has just acquired Fusus, which grants access to the camera networks of shopping centers, hospitals, residential communities, houses of worship, schools, and urban environments for more than 250 police “real-time crime centers.” Weave that data with fusion centers, and voilà, you are living in a Panopticon – a realm where you are always seen and always heard. To make surveillance even more thorough, Axon’s body cameras are being sold to healthcare and retail facilities to be worn by employees. Be nice to your nurse. Such daily progress in the surveillance state provides all the more reason for the U.S. House in its debate over the reauthorization of FISA Section 702 to include a warrant requirement before the government can freely swim in this ocean of data – our personal information – without restraint. David Pierce has an insightful piece in The Verge demonstrating the latest example of why every improvement in online technology leads to a yet another privacy disaster.

He writes about an experiment by OpenAI to make ChatGPT “feel a little more personal and a little smarter.” The company is now allowing some users to add memory to personalize this AI chatbot. Result? Pierce writes that “the idea of ChatGPT ‘knowing’ users is both cool and creepy.” OpenAI says it will allow users to remain in control of ChatGPT’s memory and be able to tell it to remove something it knows about you. It won’t remember sensitive topics like your health issues. And it has a temporary chat mode without memory. Credit goes to OpenAI for anticipating the privacy implications of a new technology, rather than blundering ahead like so many other technologists to see what breaks. OpenAI’s personal memory experiment is just another sign of how intimate technology is becoming. The ultimate example of online AI intimacy is, of course, the so-called “AI girlfriend or boyfriend” – the artificial romantic partner. Jen Caltrider of Mozilla’s Privacy Not Included team told Wired that romantic chatbots, some owned by companies that can’t be located, “push you toward role-playing, a lot of sex, a lot of intimacy, a lot of sharing.” When researchers tested the app, they found it “sent out 24,354 ad trackers within one minute of use.” We would add that data from these ads could be sold to the FBI, the IRS, or perhaps a foreign government. The first wave of people whose lives will be ruined by AI chatbots will be the lonely and the vulnerable. It is only a matter of time before sophisticated chatbots become ubiquitous sidekicks, as portrayed in so much near-term science fiction. It will soon become all too easy to trust a friendly and helpful voice, without realizing the many eyes and ears behind it. Just in time for the Section 702 debate, Emile Ayoub and Elizabeth Goitein of the Brennan Center for Justice have written a concise and easy to understand primer on what the data broker loophole is about, why it is so important, and what Congress can do about it.

These authors note that in this age of “surveillance capitalism” – with a $250 billion market for commercial online data – brokers are compiling “exhaustive dossiers” that “reveal the most intimate details of our lives, our movements, habits, associations, health conditions, and ideologies.” This happens because data brokers “pay app developers to install code that siphons users’ data, including location information. They use cookies or other web trackers to capture online activity. They scrape from information public-facing sites, including social media platforms, often in violation of those platforms’ terms of service. They also collect information from public records and purchase data from a wide range of companies that collect and maintain personal information, including app developers, internet service providers, car manufacturers, advertisers, utility companies, supermarkets, and other data brokers.” Armed with all this information, data brokers can easily “reidentify” individuals from supposedly “anonymized” data. This information is then sold to the FBI, IRS, the Drug Enforcement Administration, the Department of Defense, the Department of Homeland Security, and state and local law enforcement. Ayoub and Goitein examine how government lawyers employ legal sophistry to evade a U.S. Supreme Court ruling against the collection of location data, as well as the plain meaning of the U.S. Constitution, to access Americans’ most personal and sensitive information without a warrant. They describe the merits of the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, and how it would shut down “illegitimately obtained information” from companies that scrape photos and data from social media platforms. The latter point is most important. Reformers in the House are working hard to amend FISA Section 702 with provisions from the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, to require the government to obtain warrants before inspecting our commercially acquired data. While the push is on to require warrants for Americans’ data picked up along with international surveillance, the job will be decidedly incomplete if the government can get around the warrant requirement by simply buying our data. Ayoub and Goitein conclude that Congress must “prohibit government agencies from sidestepping the Fourth Amendment.” Read this paper and go here to call your House Member and let them know that you demand warrants before the government can access our sensitive, personal information. From Gene Schaerr, general counsel of the Project for Privacy and Surveillance Accountability:

“For months, the House Intelligence Committee warned that failure to reauthorize Section 702 would subject the American homeland to unprecedented danger. “Now the Intelligence Committee has caused the bill to be pulled rather than allow the House to work its will and vote on a few reasonable and important reform amendments. “They are now willing to endanger Section 702 in its entirety unless they get everything they want. “Think about it – the intelligence community and deep state are so determined to maintain the ability to spy on Americans that they are willing to put at risk the very authority they claim they need to protect us against foreign threats.” When the reauthorization Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act comes to the House floor later this week, both the pro-reform House Judiciary Committee and the pro-surveillance House Intelligence Committee will be offering amendments chock full of details and complexities.

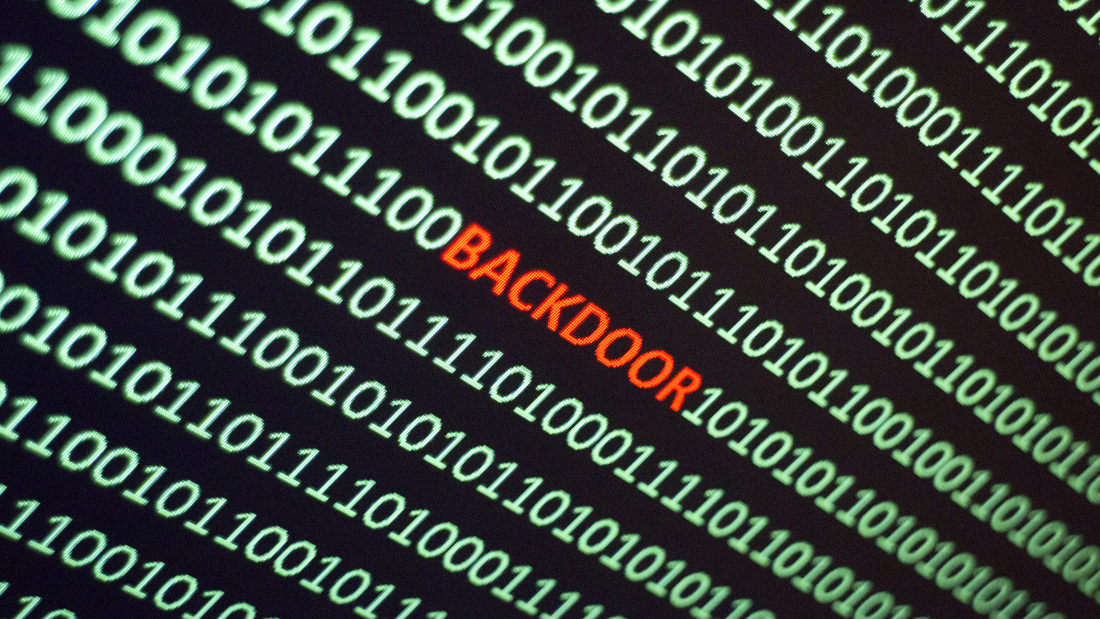

In the fog of this legislative struggle, we should remember that at heart there is one basic issue – the widespread practice of government agencies to freely examine the sensitive, personal information of Americans without a warrant. This snooping is enabled by two big loopholes in the law, practices that allow the government to act as if the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution didn’t exist. One way the government does this is through Section 702, enacted by Congress to enable the surveillance of foreign threats on foreign soil. With global communications inextricably linked, Section 702 incidentally sweeps up the communications of Americans. This database gives the government the ability to conduct “backdoor searches” of Americans without a warrant. The FBI has accessed this database millions of times in recent years, turning a program meant for foreign intelligence into a domestic spying tool. The other way the government surveils us is by buying our personal data. Our most sensitive information – including where we’ve been, what we’ve searched for, our romantic lives, our health, and financial data – are scraped from the apps on our smartphones and computers. The government then buys our information from data brokers, outside of any legal authority or oversight by a court. Both forms of snooping need to be curbed with the plain, simple warrant requirement of the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution. The House will soon consider two ways to do this: Closing the “backdoor search loophole”: This amendment requires federal agencies to get a warrant before they can inspect the Section 702-derived data of an American. Closing the “data broker loophole”: This measure, also known as the Fourth Amendment Is Not for Sale Act, requires federal agencies to get a warrant before they can view commercially purchased data that includes the sensitive, personal information of Americans. As we’ve said before, this can best be done by contacting your U.S. Representative by email or phone with this message: “Please vote to reform FISA’s Section 702 with warrant requirements, both for Section 702 data and for our sensitive, personal information sold to government agencies by data brokers.” Long before the founding of the United States, religious refugees flooded into America to escape the Star Chamber, the Inquisition, the persecutions, and wars over religious doctrine that made worship in the Old World a dangerous activity. Millions wanted relief from the incessant surveillance – exemplified by William Laud, Charles I’s Archbishop of Canterbury – that often relied on spies dispatched to listen to sermons with sharp ears for anything out of line with official orthodoxy.

As the House of Representatives prepares to decide whether to include surveillance reforms in the reauthorization of Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, there are serious implications for the free practice of religion in America. House Speaker Mike Johnson made this clear in an interview late last year when he addressed the FBI’s surveillance of traditional Catholics as possible terrorists, and the targeting of pro-life activists like Mark Hauck, whose wife and seven children watched in terror as an FBI SWAT team broke down their front door and pointed five guns at his head over a supposed violation of the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act. “I’ve made it very clear that, in my view, the evidence shows that, the FBI, for example, in the last couple of years has been weaponized,” Speaker Johnson told The Daily Signal. “We have the evidence to show it. They have, in some cases, targeted people of faith. They’ve targeted conservative Catholics and concerned parents at school board meetings … that’s what happened.” Alex Marthews of Restore the Fourth documents abuses of religious rights from church- organized civil rights protests in the 1960s to the surveillance of patriotic, law-abiding Muslims today. We recently reported on the creepy surveillance of Calvary Chapel in San Jose, California. Such government snooping into religious expression is enabled by two massive databanks that the government freely dips into without a warrant. One is Section 702, an authority that allows the surveillance of foreign targets located abroad, but incidentally collects the communications of millions of Americans. The FBI has dipped into this ocean of Americans’ communications millions of times in recent years without warrants. The other database is the commercial purchase of our most sensitive and personal information scraped from apps and sold to the FBI, IRS, Department of Homeland Security, and many other agencies. This, too, is information the government holds and freely accesses, all without a warrant. There are deep implications for the character of our nation in the growth of warrantless surveillance. Religious scholar David Lyon writes of the modern replacement of the idea of a God, who watches his creation with deep and loving concern, with the state’s Algorithm, replacing eternal joy with a perpetual living death. Or to put it in secular terms, this is the vision of George Orwell of a boot stamping on a human face forever. Any House Member who values the freedom to worship as one wishes, or not to worship at all, should take a stand for religious freedom by requiring warrants before the FBI or any other governmental agency can freely inspect our beliefs, values, and activities. This is not a new or radical notion. The founders wrote the warrant requirement into the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution to set us apart from Old World ways. Let us not go back. The word from Capitol Hill is that Speaker Mike Johnson is scheduling a likely House vote on the reauthorization of FISA’s Section 702 this week. We are told that proponents and opponents of surveillance reform will each have an opportunity to vote on amendments to this statute.

It is hard to overstate how important this upcoming vote is for our privacy and the protection of a free society under the law. The outcome may embed warrant requirements in this authority, or it may greatly expand the surveillance powers of the government over the American people. Section 702 enables the U.S. intelligence community to continue to keep a watchful eye on spies, terrorists, and other foreign threats to the American homeland. Every reasonable person wants that, which is why Congress enacted this authority to allow the government to surveil foreign threats in foreign lands. Section 702 authority was never intended to become what it has become: a way to conduct massive domestic surveillance of the American people. Government agencies – with the FBI in the lead – have used this powerful, invasive authority to exploit a backdoor search loophole for millions of warrantless searches of Americans’ data in recent years. In 2021, the secret Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court revealed that such backdoor searches are used by the FBI to pursue purely domestic crimes. Since then, declassified court opinions and compliance reports reveal that the FBI used Section 702 to examine the data of a House Member, a U.S. Senator, a state judge, journalists, political commentators, 19,000 donors to a political campaign, and to conduct baseless searches of protesters on both the left and the right. NSA agents have used it to investigate prospective and possible romantic partners on dating apps. Any reauthorization of Section 702 must include warrants – with reasonable exceptions for emergency circumstances – before the data of Americans collected under Section 702 or any other search can be queried, as required by the U.S. Constitution. This warrant requirement must include the searching of commercially acquired information, as well as data from Americans’ communications incidentally caught up in the global communications net of Section 702. The FBI, IRS, Department of Homeland Security, the Pentagon, and other agencies routinely buy Americans’ most personal, sensitive information, scraped from our apps and sold to the government by data brokers. This practice is not authorized by any statute, or subject to any judicial review. Including a warrant requirement for commercially acquired information as well as Section 702 data is critical, otherwise the closing of the backdoor search loophole will merely be replaced by the data broker loophole. If the House declines to impose warrants for domestic surveillance, expect many politically targeted groups to have their privacy and constitutional rights compromised. We cannot miss the best chance we’ll have in a generation to protect the Constitution and what remains of Americans’ privacy. Copy and paste the message below and click here to find your U.S. Representative and deliver it: “Please stand up for my privacy and the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Vote to reform FISA’s Section 702 with warrant requirements, both for Section 702 data and for our sensitive, personal information sold to government agencies by data brokers.” |

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed