|

Your phone, like your dog, knows all about you. But your dog will never tell. Your smartphone does, all day long, producing data that the federal government can buy and access without a warrant.

The same, increasingly, is true of your car. It knows where you go, and for how long. For example, Tesla has internal cameras, and according to Elon Musk biographer, Walter Isaacson, that CEO wanted them to record drivers to defend the company against lawsuits in the event of an accident. As your car integrates with your smartphone, the automobile becomes just another digital device that tracks your every move. A contemporary car can accumulate 4,000 gigabytes of data every day. Our cars’ entertainment and communications systems track our address books, call logs and what we listen to. Systems made to monitor performance can report our weight, as well as where we’ve driven, and if we’ve driven there alone or with someone else. But at least your dog in the backseat still won’t rat you out. This is just one more way digital technology is narrowing the bounds of privacy to, essentially, floatation tanks. The good news is that lawmakers in the Bay State are reacting to defend the privacy of their constituents. Two bills, one introduced in the Massachusetts House and one in the Senate, would limit collected data, set rules for the security of that data, and require it to be purged after it becomes irrelevant. Moreover, data collection would require the consent of the owner. Jalopnik.com reports that privacy advocates, however, are finding loopholes in the law “wide enough to drive a Nissan through.” Whatever the strength of these bills, Protect The 1st commends Massachusetts lawmakers for thinking around the technological curve while that very technology hurtles us ever faster, ever forward. As with AI, a sense of urgency for predictive rulemaking is in order. There was a time when talking cars were a staple of science fiction. Now our cars tell us where to go and when to turn – and sometimes won’t shut up. What our cars will do next we may not be able to quite imagine. Massachusetts has started a debate that needs to go national and in high gear. An Example of American Techno-Masochism PPSA works hard to counter growing government surveillance. This generally means surveillance by U.S. federal agencies – such as FISA’s Section 702 authority passed by Congress for foreign surveillance but used to spy on Americans. We also scrutinize expanding surveillance by state and local police, including cell-site simulators that trick your smartphone into giving up your location and other information, and ubiquitous facial recognition software that can follow you around.

But our concerns about government surveillance don’t end with just our government. We are increasingly concerned about the regular and sometimes pervasive surveillance of Americans by the People’s Republic of China, most recently the potential for Beijing to use TikTok as a way to track 80 million Americans. Now, thanks to an investigative piece in The Free Press, we’ve learned that China is also looking to surveil Americans through an increasingly common technology in American cars – LIDAR, or Light Detection and Ranging. This is the system that allows self-driving and semiautonomous cars to track the traffic around them. LIDAR is also, The Free Press reports, “a mapping technology, an aid to the growing number of smart cities, a tool for robotics, farming, meteorology, you name it.” Who is the dominant manufacturer and seller of LIDAR technology in the United States? It is Hesai, a Chinese company that sells nearly one out of every two LIDAR systems globally. In sales, it far outsells all of its American competitors together. China is relying on an old playbook to dominate the U.S. and world markets in LIDAR. The Free Press reports that Hesai does this by offering a solid product, but one backed by Chinese subsidies to sell at below price. Why would they do that? An explanation comes from Sen. Ted Budd (R-NC), who fired off a letter earlier this summer to the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Industrial Base Policy. “[I]t is my understanding that the Chinese LIDAR companies are working with the Chinese Government and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to improve this technology and leverage it for Chinese military applications. Simultaneously, these companies have been flooding the U.S. market with low-cost, heavily subsidized Chinese LIDAR, potentially enabling the Chinese to collect a trove of valuable information … “Moreover, the Chinese Government is using LIDAR sensors to conduct police surveillance in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, where evidence suggests China is engaged in ongoing genocide of the Uyghur people.” Given that Chinese law enforces a “military-civil fusion” strategy on Chinese businesses, requiring every Chinese organization and citizen to “support, assist, and cooperate with the state intelligence work,” why on earth would we allow that same government to be able to spy on every American in every near-future car? It is one thing to be forced into the position of the Uyghurs. It is quite something else for the United States to willingly submit to techno-masochism. The Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protects Americans against “unreasonable” searches and seizures. But what is unreasonable? Is a low-flying drone taking photos of you and your property behind a privacy fence reasonable?

In October, the Michigan Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in what could well become a landmark privacy case. The outcome may help determine the national limits of drone surveillance – and perhaps influence the limits of government surveillance – for all Americans. The facts are pretty simple. Todd and Heather Maxon of Long Lake Township in Michigan live on a five-acre estate, where Todd likes to repair old cars. In 2008, the Township government charged the Maxons with operating an illegal junkyard. The couple and the Township reached a settlement. In 2018, the Township received tips that the Maxons had violated their settlement by bringing more cars onto their property, even though such vehicles were not visible from the street. So the Township hired a private drone operator to fly a high-resolution camera over the Maxon property to take images. The Maxons sued, claiming that their Fourth Amendment rights were violated. A lower court agreed with the government but was overturned in 2021 by the Michigan Court of Appeals. That court ordered that the drone photos be suppressed. At the heart of this case is the “reasonable expectation of privacy” articulated by Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan II in Katz v. United States (1967). But technology keeps testing what is a reasonable expectation of privacy. The Supreme Court has zigged and zagged along the way, once upholding a wiretap to be permissible because it occurred at the telephone pole and did not require a physical intrusion into the home. Katz overturned that standard, invalidating an FBI wiretap of a public payphone, where the caller (a sports bookie) had a reasonable expectation that he would not be overheard. “The Fourth Amendment protects people, not places,” Justice Potter Steward declared in the Court’s majority opinion. But the Court returned somewhat to the physical intrusion standard – invalidating thermal imaging by police from the street that penetrated inside a target’s home in Kyllo v. United States (2001). The Cato Institute and Rutherford Institute, in an amicus brief, noted the problem with the physical intrusion standard: “At present, police are free to go through people’s garbage, look into their barn with a flashlight, and read through their bank records without going through the hassle of first securing a warrant.” We now live in an age of ubiquitous digital intrusion with government purchases of our private data, as well as optical intrusion from drones and other aerial surveillance. In other words, the current privacy standard is a jumbled mess. That is why the Maxon case is potentially so important. At its simplest, it will determine if drones – an increasingly ubiquitous reality in American life – will be freely used to spy on Americans in their backyards (as the New York City Police recently did over backyard barbecues during Labor Day). But we think the Maxon case may prove to be pivotal in defining – perhaps, eventually, by the U.S. Supreme Court – what privacy and reasonableness mean in an era of drones, facial recognition software, and artificial intelligence. For years PPSA has documented the increasing disposition of federal intelligence and law enforcement agencies to use the ever-expanding Glomar response – a “cannot confirm or deny” answer once reserved for the nation’s most closely guarded secrets – as a blanket response to any meddlesome Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests.

We should not overlook, however, another handy tool for FOIA avoidance, and that is to release the requested document but redact many or all of its meaningful parts. Now the Department of Justice Office of the General Counsel has perfected this technique, taking it to its logical end. It began in 2020 when PPSA joined with Demand Progress to file a FOIA request. Our request concerned surveillance that may be taking place under no statute, but instead under a self-professed authority of the executive branch known as Executive Order 12333. The reply from the FBI is, in its own way, telling. In the DOJ response, a certain Mr. or Ms. BLANK who holds the title of BLANK in the Office of the General Counsel returned with 40 pages of responsive documents. Thirty-nine pages are redacted in their entirety, as is the 40th page, with the redacted name of the signator and his/her redacted title, but with one, unredacted statement: Hope that’s helpful. There’s honestly no other way to take this than the Department of Justice shooting a middle finger at the very idea of a FOIA request, an exercise of the Freedom of Information Act, passed by Congress and signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson. This is a shame because the subject of this request is an important one. Demand Progress and PPSA based our FOIA request on a July 2020 letter from now-retired Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-VT) and current Sen. Mike Lee (R-UT) to then-Attorney General William Barr and then-Director of National Intelligence John Ratcliffe. The two senators noted the expiration of Section 215 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), commonly known as the “business records” provision of FISA. The intelligence community had vociferously lobbied for the renewal of Section 215 with predictions that allowing its expiration would lead to something akin to the city-destroying scenes in the 1996 movie Independence Day. Then the Trump Administration called their bluff and allowed this authority to expire. The response from the intelligence community? Crickets. The sudden complacency of the intelligence community struck many as suspicious. Were federal intelligence and law enforcement agencies shifting their surveillance to another authority? Sens. Leahy and Lee seemed to think so. They wrote: “At times the executive branch has tenuously relied on Executive Order 12333, issued in 1981, to conduct surveillance operations wholly independent of any statutory authorization … This would constitute a system of surveillance with no congressional oversight potentially resulting in programmatic Fourth Amendment violations at tremendous scale … We strongly believe that such reliance on Executive Order 12333 would be plainly illegal.” This July 2020 letter, with a detailed series of penetrating questions about the practice and scope of 12333 surveillance, was issued by two powerful and respected members of the United States Senate … And it hit the walls of the Department of Justice and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence with all the full force of wet spaghetti. As with so many other congressional requests, this letter was not answered in any substantive way. So Demand Progress joined with PPSA in October 2020, in an effort to use the law to compel an answer, this time as a formal FOIA request. We leveraged that law to request responsive documents that would reveal how the agencies might be repurposing EO 12333 to pick up the slack from the expired 215 authority, in order to spy on persons inside the United States. And this is the answer we get. It can only be taken, in a general way, as confirmation that Executive Order 12333 is, in fact, being relied upon for the surveillance of people in the United States. This is one more reason why Congress should use the reauthorization of Section 702 to seek broad surveillance reform, including significant guardrails on Executive Order 12333. With mounting evidence of abuses of Americans’ civil rights, a powerful coalition of leading conservatives and liberals in Congress is building steam to do just that. Hope that’s helpful. The output of former NSA officials in pushing for a “clean,” or unamended, reauthorization of Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act has been prolific. Several such pieces have recently run in the op-ed pages of The Hill newspaper alone.

The latest op-ed, by former senior NSA and Department of Homeland Security officials Jon Darby and Thomas Warrick, is a masterpiece of misdirection. It begins with the oft-told tale of Secretary of State Henry Stimson in 1929 closing down the “Black Chamber,” a New York City office in which government cryptographers broke the codes of Japanese and other foreign diplomats. “Gentlemen,” Stimson famously said, “do not read each other’s mail.” Stimson reversed his elevated sense of etiquette when he became Secretary of War during World War Two – and the ability to break Japanese codes became central to Allied victory. The implication here is that civil libertarians today who complain about Section 702 are sniffy idealists who would expose us to great danger. To buttress this point, Darby and Warrick cite several intelligence successes, including the breaking of the plot to bomb New York City’s subway in 2009. With Russia and China turning increasingly hostile, Darby and Warrick say that we need robust means to intercept those who threaten the safety of the American homeland. To which PPSA and many other civil libertarians say, “hurrah!” We take issue, however, with the central metaphor of their piece – Henry Stimson’s ending of foreign surveillance. No foreigner enjoys the protections of the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution. When it comes to foreign terrorists and spies, we say surveil away. Our concern arises when the communications of millions of Americans are folded into Section 702 surveillance. Whenever an American becomes a target of a government investigation, a probable cause warrant is required by the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution to examine their communications. Take the case cited by Darby and Warrick – the planned New York City bombing involving an Afghan-American who was in communication with Al-Qaeda in Pakistan and traveled to meet them. That alone should have been enough to obtain a probable cause warrant to inspect the target’s communications. Darby and Warrick acknowledge that “for a time, the FBI routinely searched databases with information collected under Section 702’s authority even in non-national security investigations.” Victims of such improper government surveillance included a Member of the U.S. House, a U.S. senator, a state senator, a judge, a local political party, and 19,000 donors to a congressional campaign, among many others. Darby and Warrick assure us that these abuses were “corrected” when “additional safeguards” were put in place. Despite large reductions in the numbers of Americans who have their data hoovered up, however, more than 200,000 warrantless searches are still taking place every year. As Sen. Mike Lee of Utah notes, the correct number for violations of the Constitution is zero. If Congress misses this rare opportunity to impose a warrant requirement, expect the FBI and other agencies to quickly revert to old ways. A final point: There is an air of unreality surrounding the debate over the Section 702 database. It is, after all, likely small compared to the database of warrantlessly obtained and inspected personal information of Americans that is commercially acquired by our government. About a dozen federal agencies, from NSA, to DoD, to IRS, to the FBI, to DHS, purchase our personal data scraped from apps and sold by third-party data brokers. Government lawyers blandly assert they are not violating the constitution’s prohibition against seizing our data. They are, after all, merely buying it. That strikes most Members of Congress and their constituents as sophistry. Our digital actions – whom we communicate with, where we go, what we search online for – can be our most personal information, revealing our romantic lives, our health issues, our religious beliefs and worship, and our political activities. Yet the government – including the agencies that Darby and Warrick served – routinely ransack what essentially are our personal diaries without a warrant or oversight of any sort. The coming debate over the reauthorization of Section 702 will be our best opportunity in a generation to curb the government’s appetite for all our information. We should not let this rare chance pass us by. While many of us were grilling hot dogs and hamburgers, the line between sci-fi dystopia and reality got a little blurrier. The New York City Police Department announced it was using aerial drones to “check in” on parties held across the city over the Labor Day weekend.

The NYPD is making the move, it says, in response to complaints about large and noisy parties during the holiday weekend. At a press conference, Assistant NYPD Commissioner Kaz Daughtry said: “If a caller states there’s a large crowd, a large party in a backyard, we’re going to be utilizing our assets to go up and go check on the party.” The practice of aerial surveillance is escalating. New York police used drones just four times in 2022 but have so far used them 124 times in 2023. Mayor Eric Adams has said he wants to see police further embrace the “endless” potential of drones. The decision is almost certainly illegal. Daniel Schwarz, a privacy and technology strategist at the New York Civil Liberties Union, says mass drone surveillance may violate the city’s Public Oversight of Surveillance Technology (POST) Act. This is an ordinance passed in 2020 that requires the NYPD to disclose its surveillance tactics. The proliferation of drones over our backyards, however, may not be unconstitutional. U.S. Supreme Court precedent on the Fourth Amendment has dealt with aerial surveillance before. In the 1988 case Florida v. Riley, the Court held that Florida did not violate a man’s right against unreasonable searches when police, on a tip, flew a helicopter over his property and observed a greenhouse in which the man was growing marijuana. The greenhouse was not visible from the ground and could only be detected aerially. But nearly 40 years have passed since Florida v. Riley, and in that time police departments across the country have been able to amass and deploy an entire fleet of small, flexible aerial drones. Whereas police might have been constrained by the cost to own and operate a helicopter in the past, today’s police departments can operate a sizable drone fleet at a fraction of the price, enabling a near permanent aerial surveillance force. Further compounding the problem is the high degree of reciprocity between local law enforcement and the national security center. A Department of Justice response to a PPSA Freedom of Information Act request shows that local governments have received fleets of drones and other surveillance technology from the federal government. As Washington floods local police forces with hovering spies, it is time for cities and states to update our laws and jurisprudence on aerial surveillance. Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-FL) recently introduced the USPIS Surveillance Protection Act, legislation that would defund the Internet Covert Operations Program (iCOP), an initiative of the United States Postal Inspection Service (USPS) that, among other things, gathers intelligence from U.S. citizens' social media posts. Under this program, yet another federal agency is assuming the disturbing power to surveil broad swaths of Americans’ digital communications.

Documents reveal that the USPS used the iCOP program to monitor social media content that revealed the when and where of planned protests and other posts it found “inflammatory.” The program was also used to monitor conservative-leaning social media sites for potential violent activity by groups like the Proud Boys. You don’t have to defend the extreme views of some of these groups to feel the tug of the slippery slope. Rep. Gaetz called the program a “clandestine domestic surveillance program,” saying, “The USP Inspection Service is operating outside of its USPS jurisdiction when it monitors internet users’ sharing of information.” The government is no stranger to using the mail service to spy on American citizens. In May, PPSA wrote that agencies often obtain so-called “mail covers,” photo images of mail envelopes. Such analog-style “metadata” can give any interested party information about whom you are writing to and who is writing back. Between 2010 to 2014, postal inspectors and law enforcement agencies requested more than 135,000 mail covers. Among the top agencies requesting mail covers were the IRS, the FBI, and the Department of Homeland Security. PPSA is pleased to see Rep. Gaetz’ bill begin to address the widespread practice of federal monitoring of Americans’ internet posts. In the era of digital communications, it is worrying to see the USPS transition from a postal to a surveillance agency. Congress must take steps to reign in this covert and lesser-known form of government spying now. When spy novelist John le Carré left MI-6 to become a writer, he said that he had resolved to have “nothing to do with the intelligence world.” Would that the same could be said of former intelligence community lawyers. During the relative quiet of August, attorneys who once served the alphabet soup of agencies – NSA, NSC, CIA – have been busy posting pieces and writing op-eds why Congressional reauthorization of Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) should be passed with minimal changes. If Congress amends Section 702 with a warrant requirement to spy on the communications of American citizens, they tell us, the nation will be in peril.

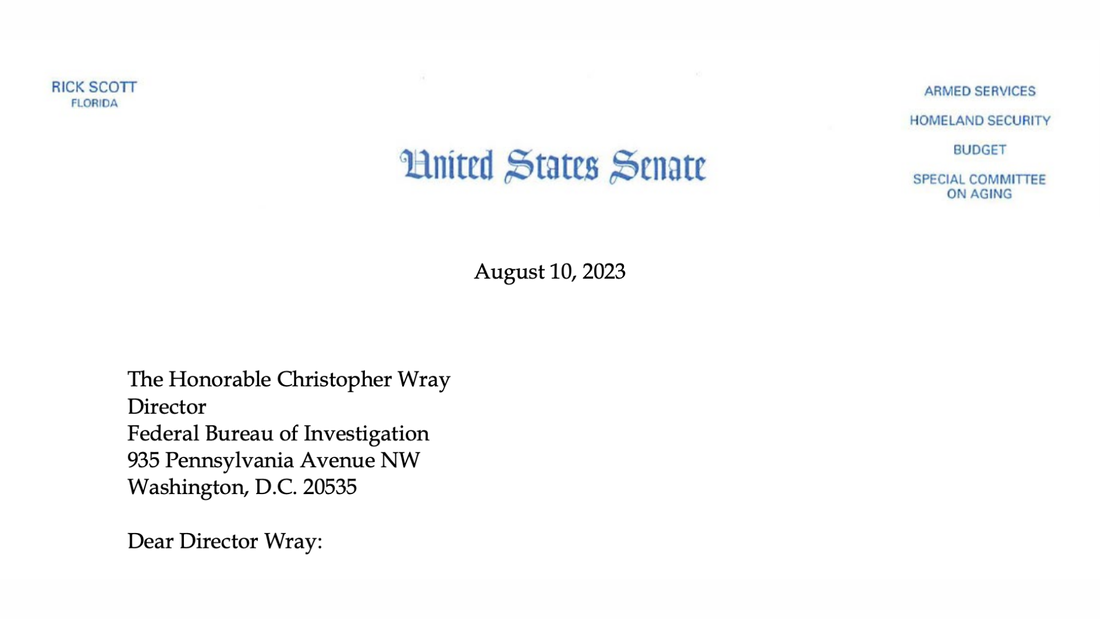

Civil libertarians are responding with vigor. Witness the incisive piece by Patrick Toomey, Sarah Taitz, and Kia Hamadanchy of the American Civil Liberties Union in the online journal justsecurity.org, a clear-eyed response to all the recent fearmongering by this intelligence community campaign. Toomey and his colleagues offer a wide-ranging survey of Section 702 and the dangers posed by how it is used in a way that is both deep and accessible. The ACLU hits the main point early and with great clarity: “If the purpose of Section 702 is to ‘target’ foreigners for intelligence gathering, then officials should have no qualms about imposing robust safeguards for Americans … but for too long, officials have tried to have it both ways – claiming that the law was not intended to spy on Americans, while using Section 702 to do just that.” ACLU more than amply demonstrates that Section 702 has become a “domestic surveillance tool, with agents and analysts routinely searching through the enormous pool of collected data for the private communications of Americans.” ACLU adds: “With that fact finally in the open, the rules written into the law should reflect the bedrock protections the Constitution requires.” This strong piece is a welcome rejoinder. As Congress prepares to return in September, defenders of the surveillance status quo have been busy warning that a warrant requirement of Section 702 would allow Chinese and Russian agents to run rampant, or that warrants would hobble law enforcement, drowning the nation in fentanyl. The ACLU’s recent piece is a sign, however, that champions of reforms are not going to let up in our corrections and rebuttals. Our coalition of civil liberties groups will be briefing leading newspapers and their editorial boards. We are reaching out to reporters to correct misleading claims and steer journalists to the right information. And we will continue to update our resource on Section 702, fisareform.org. Intelligence community disinformation is, as they say, a target-rich environment. We act in the confidence that the case for warrants and other reforms will be matters of common sense and bedrock American principles for Members of Congress and their constituents. Sen. Rick Scott (R-FL) recently fired off a letter to FBI Director Christopher Wray holding the Bureau to account for its abuses of Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act to spy on American citizens through improper, warrantless searches. The senator points to the “growing list of abuses that have come to light committed by the employees of your agency and the apparent lack of public accountability.”

Sen. Scott’s letter comes on the heels of a tidal wave of reports detailing rampant misbehavior in the FBI. To cite a recent example, PPSA reported on a Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court opinion that revealed the FBI has spied on high-level U.S. officials, including a U.S. senator, a state senator, and a judge. (The FBI had previously been caught examining the communications of Rep. Darin LaHood, Republican from Illinois). Sen. Scott wrote: “The most recent revelations of frequent and repeated abuses … by the FBI raise concerns for the American public that there are no limits—legal or otherwise—on your investigative powers even when it comes to spying on American citizens.” Sen. Scott’s letter was as substantive as it was critical, requesting the FBI to “explain the accountability for those rogue agents who conducted those illegal queries,” as well as a copy of the range of “‘possible’ disciplinary actions that could be implemented through ‘a new policy of escalating consequences.’” Sen. Scott put it best when he concludes, “the American people and their elected representatives in Congress want to believe in their government and deserve nothing short of full transparency and accountability from the FBI.” PPSA hopes the FBI will respond to this letter with more humility than the mixture of hubris and defensiveness that characterize the communications of Director Wray. The Heritage Foundation recently published a sweeping take on FBI reform by Distinguished Fellow Steven Bradbury that amounts to ripping up the current structure of the Bureau and starting over. There is much to appreciate in this iconoclastic report, with far-reaching changes that warrant careful review on Capitol Hill.

Here are some of Bradbury’s more intriguing proposals to “reimagine the FBI from the ground up”:

In addition to these structural changes, the report proposes a minimum set of actions required to end the FBI’s abuses of its authority. Worthy and sensible recommendations include reforms to insulate the FBI from the Section 702 program, to require the FISA Court to appoint an amicus in all politically sensitive cases involving U.S. persons, and to improve oversight of politically sensitive FBI investigations. PPSA commends Heritage for thinking outside of the Beltway box; however, countering FBI abuses is just one Washington element in need of reform. We are hopeful Congress will also focus on reforming Section 702, end warrantless data purchases, and address other abuses of Americans’ civil liberties. On Aug. 5, The Wall Street Journal gave readers an uncharacteristically off take about Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. The Journal posed a false dichotomy – we must either reauthorize Section 702 as it is, or let it lapse and expose Americans to the next terrorist attack.

Bob Goodlatte, PPSA Senior Policy Advisor and former Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, offered this response in a letter-to-the-editor. Americans who rely on WhatsApp, Signal, Telegram, and other encrypted messaging services for private conversations may soon have this option taken away from us – by the British House of Lords.

The UK Parliament is close to passing the Online Safety Bill, which will give the UK government the power to scan every message online. The stated purpose is to catch child abusers and terrorists. A blog posted by Element, the UK’s popular encrypted app, says the bill will be “the online equivalent of installing a CCTV camera into everyone’s bedroom, hooked up to an artificial intelligence classifier which sends footage back to the authorities whenever it thinks it sees something illegal happening.” The Element blog says that Apple (which has joined the coalition in opposition to this bill) has built-in scanning technology that has trouble distinguishing a cow from a horse. “The privacy implications are catastrophic.” Worst of all, the bill would likely defeat its own noble purpose. Once backdoors are introduced into encrypted services, tyrannical governments, terrorists, cartels, and abusers of women and children will eventually get their hands on it. The likely victims will be journalists and whistleblowers, dissidents, and women and their children hiding in shelters from their persecutors. “It means that healthcare information, financial details, conversations regarding air-traffic control, electricity grids, nuclear power plants, military maneuvers … none of it would be protected by end-to-end encryption,” blogger Matthew Hodgson writes on the Element blog. “Bad actors don’t play by the rules.” Such a capability would also give governments the means to deepen the censorship of the internet. If anyone doubts official determination to do so, the UK government recently added an amendment to this bill that “posting videos of people crossing the Channel that show that activity in a positive light” should be considered “priority illegal content.” Imagine if such tools of censorship were to be applied by either U.S. political party to the controversies surrounding the southern border of the United States, or any other contentious issue. Worse, the UK bill would hammer home the power of censorship, at least in the UK, with a threat of criminal sanctions for individual senior managers of online platforms. Hearing the tinkling of the jailer’s key, every executive would become a willing censor. If the UK presses forward with this bill, it will break end-to-end encryption, “opening the door to routine, general and indiscriminate surveillance of personal messages of friends, family members, employees, executives, journalists, human rights activists and even politicians themselves.” And that train of bad consequences will happen everywhere, including here in the USA. Any decent person wants to combat child abuse and terrorists. But it should not come about by involving millions of innocent people as collateral casualties, while arguably undermining the very noble goals of this legislation. The recently departed novelist, Milan Kundera, wrote that “a man who loses his privacy loses everything.” The Electronic Frontier Foundation is organizing a worldwide response. Americans can register our protest directly to Parliament here. PPSA is asking a DC federal court to compel the top federal intelligence and law enforcement agencies to search for records related to how they acquire and use the private, personal information of 110 Members of Congress purchased from third-party data brokers.

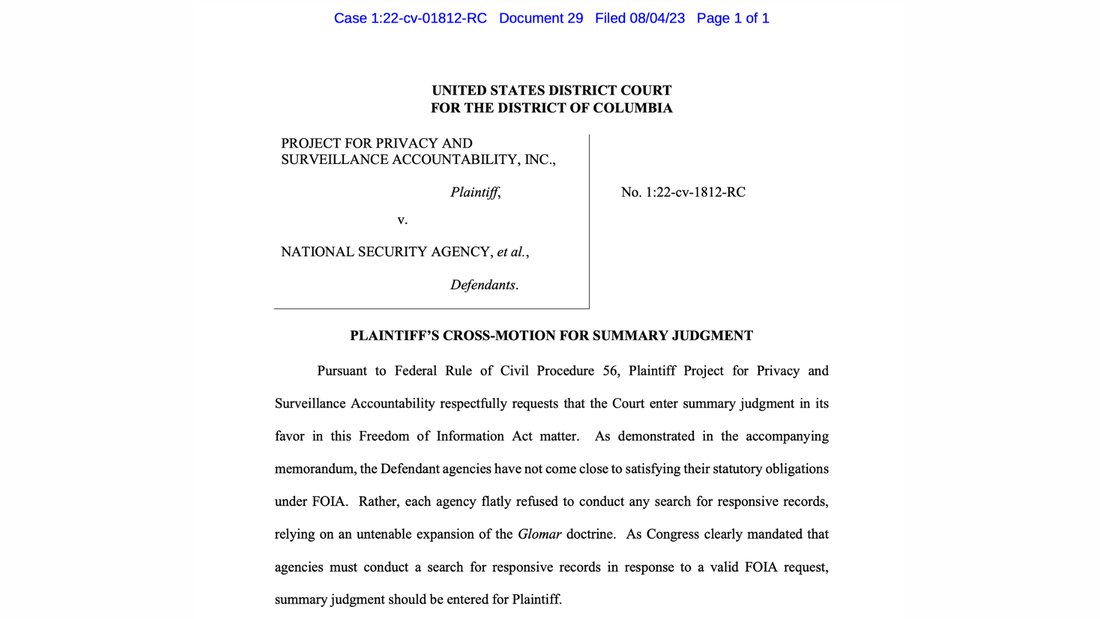

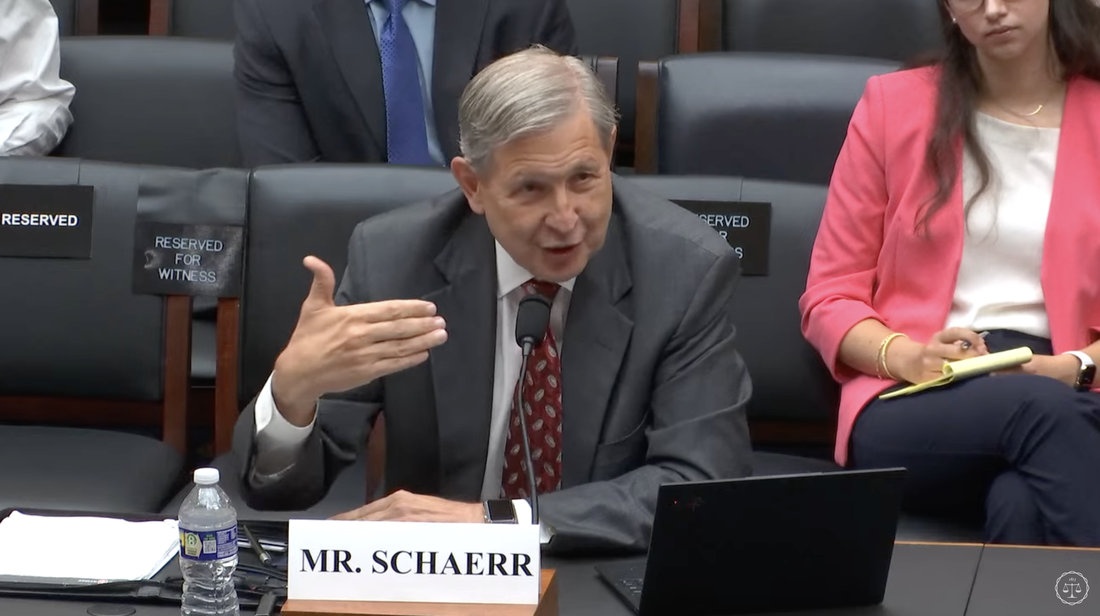

In a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request filed in July, 2021, PPSA had asked the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the National Security Agency, the Department of Justice and the FBI, and the CIA for records related to the possible purchase and use of commercially available information on current and former members of the House and Senate Judiciary Committees. The request covered such leading Members of Congress as House Judiciary Chairman Jim Jordan, Ranking Member Jerry Nadler, Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Dick Durbin, Ranking Member Chuck Grassley, and former Members that included Vice President Kamala Harris and Florida Governor Ron DeSantis. PPSA’s motion for summary judgment filed before the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia confronts the assertion by these multiple agencies that to even search for responsive documents would harm national security. PPSA’s motion notes that under FOIA, “agencies must acknowledge the existence of information responsive to a FOIA request and provide specific, non-conclusory justifications for withholding that information.” The agencies instead stonewalled this FOIA request by invoking the judge-created Glomar response, meant to be a rare exception to the general rule of disclosure, which allows the government to neither confirm nor deny the existence of such records. “Requiring Defendants here to perform FOIA searches within the secrecy of their own silos does not, by itself, compel the automatic disclosure of any information whatsoever," PPSA declares in its motion. “[B]ecause the initial step of conducting an inter-agency search makes no such disclosure, their arguments are neither logical nor plausible justifications for shirking their duty to perform an internal search.” The issue of government spying into the private, personal information of Members of Congress, tasked with oversight of these agencies, involve the serious potential for executive intimidation of the legislative branch. The ODNI recently declassified an internal document noting that commercially available information can be used to “facilitate blackmail, stalking, harassment, and public shaming.” “The government doesn’t even want to entertain our question,” said Gene Schaerr, PPSA general counsel. “What do they have to hide?” PPSA previously commented on a New York Times scoop in April that revealed a contractor for the U.S. government had purchased and used a spy tool from NSO, the Israeli firm that developed and released Pegasus software into the wild – which can turn smartphones into pervasive surveillance tools.

The White House was surprised that its own government did business with NSO a few days after the administration had put that firm on the no-business “Entity List.” NSO was placed on this blacklist because its products, the U.S. Commerce Department declared, “developed and supplied spyware to foreign governments that used these tools to maliciously target government officials, journalists, businesspeople, activists, academics, and embassy workers.” Understandably upset, the White House tasked the FBI to sleuth out who in the government might have violated the blacklist and used the software. Mark Mazzetti, Ronen Bergman, and Adam Goldman of The Times report that months later the FBI has come back with a definitive identification of this administration’s scofflaw. The FBI followed the breadcrumbs and discovered, you guessed it, that it was the FBI. Fortunately, the FBI did not purchase the “zero-day” spyware Pegasus, but another spy tool called Landmark, which pings the cellphones of suspects to track their movements. The FBI says it used the tool to hunt fugitives in Mexico. It also claims that the middleman, Riva Networks of New Jersey, had misled the FBI about the origins of Landmark. Director Christopher Wray discontinued this contract when it came to light. Meanwhile, The Times reports that two sources revealed that contrary to the FBI’s assertions, cellphone numbers were targeted in Mexico in 2021, 2022, and into 2023, far longer than the FBI says Landmark was used. We should not overlook the benefits of such FBI investigations. In fact, PPSA has a tip to offer. We suggest that the FBI track down the government bureau that has been routinely violating the U.S. Constitution by conducting backdoor searches with FISA Section 702 material, as well as warrantlessly surveilling Americans purchased data. More to follow. July was a banner month for surveillance reform. For years, civil libertarians have warned about the widespread practice of third-party data brokers selling Americans’ most sensitive and private information, scraped from our apps, to more than a dozen federal intelligence and law enforcement agencies, including the FBI, Drug Enforcement Administration, and the many agencies of the Department of Homeland Security.

The public is alarmed. Lawmakers in both parties are beginning to take effective action. In July, the House Judiciary Committee unanimously passed The Fourth Amendment Is Not for Sale Act, which would restrict the ability of government agencies to warrantless extract Americans’ personal information from data purchases. Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR) is reintroducing this measure in the Senate. If the will of the Congress wasn’t clear enough, also in July the House passed an amendment sponsored by Rep. Warren Davidson (R-OH) and Sara Jacobs (D-CA) to the National Defense Authorization Act that expressly prohibits half of the intelligence community, including the NSA and the Defense Intelligence Agency, from purchasing our data at all, absent a warrant, court order, or subpoena. Supporters of similar reforms range from the conservative Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, Jim Jordan, to the liberal Ranking Member and former Chairman, Jerry Nadler. A passion for surveillance reform brings together respected members from Rep. Thomas Massie (R-KY) to Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-CA), from Sen. Wyden to Sen. Mike Lee (R-UT). It might seem, then, that surveillance reform is now a slam-dunk certainty. It isn’t. Consider the fate of Lee-Leahy, a bill that would have imposed the rather modest goal of requiring the judges of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) court to seek the advice of civil liberties experts in cases that involve significant civil rights concerns when political, religious, or journalistic groups are surveilled and investigated. That measure passed the Senate in 2020 by an overwhelming 77 votes. Then, through a process of legislative confusion and the Trump Administration’s policy contortions, this modest and popular bill sailed into the round file like a paper airplane. The Davidson-Jacobs Amendment and The Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act risk dying in a far less dramatic way than Lee-Leahy did. All the elected champions of the surveillance state have to do is let these measures die in the darkness of a committee room or the Senate calendar. More good legislation has been killed by benign neglect than by explicit filibusters. Any American who cares about privacy and civil liberties must draw two conclusions from this realization. First, now more than ever, civil libertarians need to ramp up the activity. Members of Congress must know that this year we won’t settle for feel-good, symbolic votes. The Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act must get a floor vote in the Senate. Second, civil libertarians must continue to insist that FISA’s Section 702, an authority under which the government surveils foreigners, must be reformed so that it cannot continue to be used by the FBI and other agencies as a domestic surveillance tool. This reform must necessarily include closing the legal loophole that allows the government to buy our personal information and thumb through it, all without a warrant. As Kenny Loggins sang so long ago, “this is it!” Our back is to the corner. Join the efforts of the civil liberties community by clicking here to stand up and fight! The unanimous passage of the Fourth Amendment Is Not for Sale Act by the House Judiciary Committee, as well as the expiration of Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, is spurring the National Security Agency into a furious lobbying campaign of the public and Congress to stop surveillance reform.

NSA lobbyists argue that it would be hobbled by the House measure, which would require agencies to obtain a probable cause warrant before purchasing Americans’ private data. Former intelligence community leaders are also making public statements, arguing that passage of Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) with any meaningful changes or reforms would simply be too dangerous. George Croner, former NSA lawyer, is one of the most active advocates of the government’s “nothing to see here, folks” position. In March, Croner portrayed proposals for a full warrant requirement as a new and radical idea. He quoted two writers that concern over warrantless, backdoor searches is a concern of “panicky civil libertarians” and right-wing conspiracy theorists. In a piece this week, Croner co-authored a broadside against the ACLU’s analysis of the NSA’s and FBI’s mass surveillance. For example, Croner asserts that civil liberties critics are severely undercounting great progress the FBI has made in in reducing U.S. person queries, a process in which agents use the names, addresses, or telephone numbers of Americans to extract their private communications. Croner celebrates a 96 percent reduction in such queries in 2022 as a result of process improvements within the FBI. But, to paraphrase the late, great Henny Youngman, 96 percent of what? Ninety-six percent of a trillion data points? A quadrillion? The government’s numbers are murky and ever-changing, but the remaining amount appears, at the very least if you take these numbers at face value, to constitute well over 200,000 warrantless searches of Americans. Elizabeth Goitein of the Brennan Center for Justice, who has placed her third installment in a series on Section 702 in the online outlet Just Security – a masterclass on that program and why it must be reformed – has her own responses to Croner. While Croner portrays a warrant requirement for reviewing Americans’ data as a dangerous proposal, Goitein sees such a requirement as way to curb “backdoor searches,” and return to the guarantees of the Fourth Amendment. Goitein writes: “For nearly a decade, advocates, experts, and lawmakers have coalesced around a backdoor search solution that would require a warrant for all U.S. person queries conducted by any U.S. agency. Indeed, some broadly supported proposals have gone even further and restricted the type of information the government could obtain even with a warrant.” She describes a Review Group on Intelligence and Communications Technologies that included many, like former CIA acting director Michael J. Morrell, who are anything but panicky civil libertarians. This group nevertheless found it responsible to recommend warrants “based on probable cause” before surveilling a United States person. Other supporters of probable cause warrants range from Rep. Thomas Massie (R-KY) and Zoe Lofgren (D-CA), to Sens. Dianne Feinstein (D-CA), Mike Lee (R-UT), and former Sen. Kamala Harris (D-CA). They all saw what Goitein describes: “Without such a measure, Section 702 will continue to serve as an end-run around the protections of the Fourth Amendment and FISA, and the worst abuses of the power to conduct U.S. queries will continue.” We eagerly await ACLU’s response to Croner’s critique. Such debates, online and perhaps in person, are the only way to winnow out who is being candid and who is being too clever by half. It is a healthy development for intelligence and civil libertarian communities to debate their clashing views before the American people and the Congress rather than leave the whole discussion to secret briefings on Capitol Hill. Does the Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination prevent the government from forcing a defendant to unlock their cellphone? That’s the question at issue in People v. Sneed, a recent case brought before the Illinois Supreme Court, which found in favor of the state.

This ruling is a blow to Fifth Amendment protections in the digital age and an interpretation that cannot be sustained if we are to properly extend constitutional protections to ever-evolving technology. In an amicus brief before the court, the American Civil Liberties Union aptly laid out the arguments against compelling passwords from the accused. Fifth Amendment protections against self-incrimination, they point out, derive from the founders’ fears of an American “Star Chamber,” the English judicial body that became synonymous with oppressive interrogation tactics and a lack of due process. Drawing on this foundation, the American legal system has largely supported the notion that “the State cannot compel a suspect to assist in his own prosecution through recall and use of information that exists only in his mind.” To do so would impose a “cruel trilemma” on a defendant who would face an impossible choice: perjury, self-incrimination, or contempt of court. As the ACLU points out, numerous high courts (including Indiana and Pennsylvania) have found that password disclosure constitutes testimony because it draws from “the contents of one’s mind.” Yet courts in New Jersey and Massachusetts have sided with Illinois, presenting a significant conflict of law in the ongoing effort to adapt constitutional precepts to our changing society. In finding for the state and forcing the defendant, Sneed, to unlock his cellphone, the Illinois Supreme Court drew on a somewhat obscure legal exception to the Fifth Amendment right against self-incriminating testimony known as the “foregone conclusion” doctrine. That exception, which the Supreme Court of the United States has applied only once before, holds that producing a password is not testimonial when the government can show, with reasonable particularity, that it already has knowledge of the evidence it seeks, that the evidence was under control of the defendant, and that the evidence is authentic. The idea is that the act of producing a password has little testimonial value in and of itself. The court misapplied that doctrine here, placing the focus on the password rather than the contents of Sneed’s cellphone. The court drew on precedents that probable cause justifies the intrusion: “Any information that may be found on the phone after it is unlocked is irrelevant, and we conclude that the proper focus is on the passcode.” But probable cause does not constitute evidentiary certainty. And, in applying its analysis to passcodes rather than the contents of a safe or lockbox or cellphone, the court ignores that the Supreme Court of the United States’ use of this exception in Fisher v. United States (1976) depended on a specific, narrow set of facts. There, the analysis focused on the production of business documents already proven to exist – not on a passcode. Allowing the “foregone conclusion” exception to apply to testimonial production of cellphone passwords opens the door to forcible government snooping across the vast scope of our digital lives. Gaining access to someone’s cellphone can reveal anything and everything about that person – including the most intimate details of a life. As the ACLU put it: “Locked phones and laptops may impose obstacles to law enforcement in particular cases. So do window shades. It is sometimes true that constitutional protections interfere with law enforcement investigations.” Until the Supreme Court of the United States resolves this issue, our Fifth Amendment rights in the digital age remain in doubt. On Friday, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence released a Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court opinion that details blatant violations of Americans’ privacy. Most distressingly, high-profile American political leaders were among the targets surveilled by the FBI. The heavily redacted opinion released on Friday reveals that the FBI attempted improper searches of the communications of a United States Senator, a state senator, and a judge who complained about civil rights violations by local police.

If that sounds beyond the pale, the National Security Division (NSD) of the United States Department of Justice thought so, too. In the former case, the NSD determined that the “querying standard” used by the FBI to obtain foreign intelligence information was not met. In the latter case, it’s a little more opaque. Last October, the FBI used the anonymous Judge’s social security number to search the Section 702 database. The Judge "had complained to FBI about alleged civil rights violations perpetrated by a municipal chief of police.” The National Security Division’s review stated that this search was also illicit. While the U.S. Senator has been notified about the improper search, the state Senator and the state Judge have not. It is clear is that a continued pattern of government abuse persists when it comes to Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. Although the FISC states that, “there is reason to believe that the FBI has been doing a better job in applying the querying standard,” the anonymous judge also admits that “[t]he prevalence of non-compliant queries conducted by the FBI, and particularly of broad queries that were not reasonably likely to return foreign intelligence information or evidence of crime, has been a major focus of concern….” Indeed it has been. In fact, the same court found in 2018 that there was a “deficiency in the FBI’s querying and minimization procedures” based on “large-scale, suspicionless queries….” The Court found that the FBI’s implementation of remedial measures has improved the Bureau’s compliance with Section 702’s specificity requirements. But they make sure to soften that finding with a disclaimer: “NSD devotes substantial resources to its oversight efforts, but still can examine only a fraction of total FBI queries. It is therefore possible that serious violations of the querying standard have so far gone undetected.” The FBI has a long track record of repeatedly misusing the Section 702 database, but to poll information on high-profile elected officials is a new level of abuse. These revelations come amid a push by the Biden administration to reauthorize Section 702 mere months before it expires at the end of this year. When federal authorities inappropriately attempt to spy on legislators – and even judges – we truly find ourselves with one foot off the merry-go-round. Congress must take this into account in the coming months. In late 2022, pursuant to its internal policy, Google informed two customers about law enforcement action taken against them by the Department of Justice five years prior. The customers in question: Republican staffers working for then-House Intelligence Committee Chairman Devin Nunes. According to contemporaneous reports, authorities subpoenaed addresses, screen names, telephone and payment records, and “all customer and subscriber account information” related to the two staffers. What’s more, as the Wall Street Journal editorial board recently pointed out, this was apparently done without informing Congress, as is typical practice.

One of the targeted staffers was Kash Patel, who at the time served as senior counsel to the House Intel Committee. Given the Committee’s focus at the time – looking into the origins of the FBI’s investigation of alleged collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia – some dot-connecting might well be warranted. What truly shocks the conscience, however, is that Justice would clandestinely spy on Congress in the first place. As the Wall Street Journal wrote, “If DOJ used its law enforcement tools to snoop on Mr. Nunes, that would be an abuse of power.” Now, House Judiciary Chairman Jim Jordan has issued a letter to FBI Director Christopher Wray demanding answers. All who care about data privacy – and the integrity of congressional authority – deserve them. PPSA’s Gene Schaerr Appeals to Congress to Assert Its Authority to Protect Americans’ Privacy and the Fourth AmendmentEnd the “Game of Surveillance Whack-a-Mole" Gene Schaerr, PPSA general counsel, in testimony before a House subcommittee on Friday, urged Congress to assert its prerogative to interpret Americans’ privacy and Fourth Amendment rights against the federal government’s lawless surveillance.

Schaerr said the reauthorization of a major surveillance law this year is a priceless opportunity for Congress to enact many long-needed surveillance reforms. There is, Schaerr told the Members of the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Crime and Government Surveillance, no reason for Congress to defer on such a vital, national concern to the judiciary. Congress also needs to assert its authority with executive branch agencies, he said. For decades, when Congress reforms a surveillance law, federal agencies simply move on to other legal authorities or theories to develop new ways to violate Americans’ privacy in “a game of surveillance whack-a-mole.” Schaerr said: “As the People’s agents, you can stop this game of surveillance whack-a-mole. You can do that by asserting your constitutional authority against an executive branch that, under both parties, is too often overbearing – and against a judicial branch that too often gives the executive an undeserved benefit of the doubt. Please don’t let this once-in-a-generation opportunity slip away.” Schaerr was joined by other civil liberties experts who described the breadth of surveillance abuse by the federal government. Liza Goitein of the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU Law School said that FISA’s Section 702 – crafted by Congress to enable foreign surveillance – has instead become a “rich source of warrantless access to Americans’ communications.” She described a strange loophole in the law that allows our most sensitive and personal information to be sold to the government. The law prevents social media companies from selling Americans’ personal data to the government, but it does not preclude those same companies from selling Americans’ data to third-party data brokers – who in turn sell this personal information to the government. Federal agencies assert that no warrant is required when they freely delve into such purchased digital communications, location histories, and browsing records. Goitein called this nothing less than the “laundering” of Americans’ personal information by federal agencies looking to get around the law. “We’re a nation of chumps,” said famed legal scholar and commentator Jonathan Turley of the George Washington University Law School, for accepting “massive violations” of our privacy rights. He dismissed the FBI’s recent boasts that it had reduced the number of improper queries into Americans’ private information, likening that boast to “a bank robber saying we’re hitting smaller banks.” Many members on both sides of the aisle echoed the concerns raised by Schaerr and other witnesses during the testimony. Commentary from the committee indicates that Congress is receptive to privacy-oriented reforms. Gene Schaerr cautioned that Congress should pursue such a strategy of inserting strong reforms and guardrails into Section 702, rather than simply allowing this authority to lapse when it expires in December. Drawing on his experience as a White House counsel, Schaerr said the “executive branch loves a vacuum.” Without the statutory limits and reporting requirements of Section 702, the FBI and other government agencies would turn to other programs, such as purchased data and an executive order known as 12333, that operate in the shadows. Despite this parade of horribles, the hearing had a cheerful moment when it was interrupted by the announcement of a major reform coalition victory. The Davidson-Jacobs Amendment passed the House by a voice vote during a recess in the hearing, an announcement that drew cheers from witnesses and House Members alike. This measure would require agencies within the Department of Defense to get a probable cause warrant, court order, or subpoena to purchase personal information that in other circumstances would require such a warrant. Schaerr was optimistic that further reforms will come. He said: “Revulsion at unwarranted government surveillance runs deep in our DNA as a nation; indeed, it was one of the main factors that led to our revolt against British rule and, later, to our Bill of Rights. And today, based on a host of discussions with many civil liberties and other advocacy groups, I’m confident you will find wide support across the ideological spectrum for a broad surveillance reform bill that goes well beyond Section 702.” Last month, we wrote about a surprisingly frank report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence admitting the government’s increasing role in utilizing Commercially Available Information about United States citizens for investigative purposes. Despite the Supreme Court’s ruling in Carpenter v. United States, which held that a warrant is required before the government can seize location history from cell-site records, the report candidly reveals that the bulk collection of Americans’ private data continues unabated. Now, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is taking steps to ban the purchase and sale of location data altogether. It’s a blunt solution to a complex issue, and a bellwether for where this debate might be headed.

“Location data” refers to information about the geographic locations of mobile devices like smartphones or tablets. When collected, this data can be used for relatively benign purposes like marketing – but also to identify the movements of individuals and discern their identities (a 2013 study found that only four spatio-temporal data points are required to identify someone in most circumstances). A host of companies collect this information, package it, and sell it to private actors like advertisers – and, increasingly, law enforcement agencies. The government can learn a lot about you based on your movements – and they know it. For example, the FBI has its own team dedicated to analyzing cell tower data. A growing number of states are now taking action to protect the digital privacy of their residents. Laws passed in California and Virginia require the affirmative consent of consumers before geolocation data can be used for specified purposes. The European Union has gone further, prohibiting the use of sensitive data by default unless a company can demonstrate that its use falls under a specifically enumerated exemption. In the United States, Massachusetts’ Location Shield Act (H.357|S.148) is by far the most comprehensive effort yet to protect our data from unwarranted (or warrantless) snooping. The bill’s drafters couch it within a social policy framework; it’s described as “An Act protecting reproductive health access, LGBTQ lives, religious liberty, and freedom of movement by banning the sale of cell phone location information.” Such concerns are not unfounded. As the ACLU writes, “In the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision…journalists found that data brokers have continued to buy, repackage and sell the location information of people visiting sensitive locations including abortion clinics. This puts people who seek or provide care in our state at risk of prosecution and harassment, creating a vulnerability in our state’s post-Roe protections.” Beyond addressing those concerns, however, the bill does a lot to broadly reinforce our Fourth Amendment rights against unreasonable searches and seizures, implementing a warrant requirement for any law enforcement access to location data. Such restrictions would clear away some of the murk surrounding this issue in the wake of the Carpenter case, which required a warrant when accessing location data from phone companies, but which holds limited relevance when such data are readily available for commercial purchase. (Obviously, the same legal reasoning should apply.) Americans are waking up to the dangers of the $16 billion data brokerage industry. In Massachusetts, 92% of survey respondents said the government should enshrine stronger protections for consumer data – all the way back in 2017. Whether this bill makes it over the finish line or not, it’s a clear sign that Americans want comprehensive data privacy reform. And Massachusetts’ solution is one we’ll readily share. PPSA previously sent an appeal to every Member of the U.S. House urging them to vote for the Davidson-Jacobs Amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). It would place significant restrictions on the government’s purchase of Americans’ Fourth Amendment-protected sensitive, personal information without a warrant.

We attached to our letter the endorsement of this measure from more than 40 civil liberties allies—ranging from the ACLU to FreedomWorks, from the Brennan Center and Demand Progress to Americans for Prosperity and the Due Process Institute. The strong bipartisan support in the House led to the passage of this important measure by voice vote. “This vote is vital because our digital histories reveal our personal lives—where we’ve been, who we’ve met or communicated with, what we’ve searched for online, even our medical issues,” we wrote. “A digital portrait can be more personal and intimate than a diary. “Yet, under current practice, federal agencies purchase our most sensitive and personal information scraped from apps and sold by third-party data brokers. The general counsels of intelligence and law enforcement agencies assert a right to see our most personal information without the need to get a warrant, in flagrant disregard of the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution.” “This is the kind of practice one expects of a surveillance state, not America.” The House now officially agrees. This measure would require agencies within the Department of Defense to get a probable cause warrant, court order or subpoena to purchase personal information that in other circumstances would require such a warrant. “This amendment strikes a reasonable balance between respecting the privacy of Americans while leaving the government with the power to search for potential threats to the homeland,” says Bob Goodlatte, PPSA Senior Policy Advisor. “The Senate should respect the groundswell of bipartisan support shown in the House today for this amendment in the NDAA.” In today’s House Committee Judiciary hearing with FBI Director Christopher Wray, Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) expertly revealed the extent to which the FBI is unwilling to publicly discuss its use of commercially available information (go to 1:10:50 mark).

Rep. Jayapal asked the director about his claim before the Senate Intelligence Committee in March that the FBI had previously purchased Americans’ location data information from internet advertisers but had stopped the practice. Why, then, Jayapal asked, did a report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) reveal that the government continues to purchase Americans’ personal data scraped from apps and sold to the government by third-party data brokers? The report was surprising for its frankness. An ODNI panel admitted that such data can be used to “facilitate blackmail, stalking, harassment, and public shaming.” Rep. Jayapal asked how the FBI uses such data. Director Wray responded that this is too complex to cover in a short exchange. He said there are so many precise definitions that he had best send “subject matter experts” from the FBI to give Rep. Jayapal a briefing, presumably behind closed doors and under classified rules that would prevent public discussion. Rep. Jayapal then went on to note that more than historic location data is at stake. Purchased data, she said, include biometric data, medical and mental health records, personal communications, and internet search histories and activities. She asked Director Wray: Does the FBI have a written policy on how it uses such commercially available information? Director Wray did not seem sure. He replied that he would be happy to provide a private briefing. Rep. Jayapal next asked if there is an FBI policy for using purchased information against Americans in criminal cases. Once again, Director Wray punted. After Rep. Jayapal was finished, House Judiciary Chair Jim Jordan (R-OH), said that her remarks were “well said,” and promised a bipartisan approach on the issue. Speaking for Republicans, Chairman Jordan told Rep. Jayapal, chair of the progressive caucus, “you have friends over here who want to help you with that.” We suggest that a bipartisan next step could be an open hearing with the FBI’s experts on how much purchased information is obtained and how it is used. ACLU is celebrating the 15th anniversary of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) amendments by highlighting a floor statement President Joe Biden made as a U.S. Senator in 2008.

In his Congressional Record submission, Sen. Biden declared the measure that we would come to know as Section 702 as “constitutionally infirm.” He voted against it. Sen. Biden’s words would be a better guide to President Biden’s surveillance policies than those advocated by his appointees and representatives today. For months now, the administration’s representatives on Capitol Hill have argued that Section 702 of FISA should be reauthorized without changes or reforms. FBI Director Christopher Wray and others have, with the backing of the president, made this case even though, by the administration’s own admission, this authority meant by Congress to authorize surveillance of foreigners located abroad has been used in 246,000 targeted searches of Americans’ communications. While we should not uncritically accept the government’s numbers, and the definitions and assurances behind it, let’s take the government’s number as a minimum. The question remains why the government believes 246,000 violations of Americans’ civil liberties is acceptable. That number constitutes millions of civil rights violations in a few years and more violations than there are people in a sizable city, say, Richmond, Virginia. As a U.S. Senator, Joe Biden foresaw problems with Section 702. He complained that the law authorized only weak judicial oversight by the FISA Court, beholden to the good faith of executive branch officials. Sen. Biden said the Attorney General and the Director of National Intelligence would certify after the fact to the FISA court that they had good reason to believe targets were located outside of the United States, “regardless of how many calls to innocent American citizens inside the United States were intercepted in the process.” “This would be a breathtaking and unconstitutional expansion of the President’s powers,” Sen. Biden said. Now those powers are in the hands of President Joe Biden. As senator, Joe Biden set out an overarching principle we’d all be wise to remember: “One of the defining challenges of our age is to combat international terrorism while maintaining our national values and our commitment to the rule of law and individual rights. These two obligations are not mutually exclusive. Indeed, they reinforce each other.” PPSA has been hearing as much from Congressional leaders, from Democrats as well as Republicans. Our point is not to slam Joe Biden for inconsistency, but to sharpen the debate for Members of Congress. The president was right the first time: We can have protection from terrorists and spies without jettisoning our civil rights. We can reform Section 702 so it will work within the guardrails of the Constitution. Sens. Ron Wyden and Rand Paul are renewing their push for the Protecting Data at the Border Act, a bill to ensure that government agents, including agents of Customs and Border Protection, obtain a warrant to search the personal data of Americans returning from abroad. The measure would send a resolute message: Americans' digital privacy is guaranteed, even at the border.

Until 2014, the federal government claimed it did not need a warrant to search a device if a person had been arrested. In Riley v. California, a landmark Supreme Court case, the Justices unanimously held that the warrantless, deep search of the digital contents of a cell phone during an arrest is unconstitutional under the Fourth Amendment. If this principle pertains to an arrestee, how much more should it pertain to an American citizen who is merely traveling? Yet border zones, whether points of entry to Canada or Mexico, or airports, have become legal twilight zones where the Fourth Amendment is treated as a suggestion. With ever-increasing international traffic, the potential for government misconduct grows as well. PPSA has called attention to constitutional loopholes at the border before. In 2021, we reported that two troubling trends at the border threatened the rights of Americans. One is the rollout of facial recognition technology and other biometric surveillance by Customs and Border Patrol, which is used on citizens and non-citizens who arrive at a U.S. airport. The other – and by far the most intrusive – is the existing practice of accessing the contents of returning citizens’ cellphones, laptops, and other electronic devices. In 2017, a NASA employee was stopped by Customs and Border Patrol agents and told he could not leave until he gave CBP agents his password to his phone, which belonged to NASA and contained sensitive and confidential information. In an ACLU petition filed to the Supreme Court in 2021 (Merchant v. Mayorkas), eleven U.S. citizens sued over having their electronic devices examined at the border without a warrant or reasonable suspicion. Unfortunately, the Court declined to hear the case. PPSA endorses the Protecting Data at the Border Act. This bill will go a long way towards codifying and ensuring that the Fourth Amendment protects American citizens at the border. The bill will also prohibit officials from delaying or denying entry to the U.S. if a person declines to hand over devices and requires law enforcement to have probable cause to seize a device. Bob Goodlatte, PPSA senior policy advisor and former Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, said: “There is no excuse for the government to suspend the Fourth Amendment at the border. While it is reasonable for border agents to protect the nation with inspections for pests, contraband, and illegal narcotics, it is an outrageous violation of the Constitution for agents to scan the contents of our digital devices, delving into the sensitive and personal aspects of our domestic lives. “Sens. Ron Wyden and Rand Paul are stepping up to remind the government that we don’t shed our constitutional rights just because we travel.” |

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed